Danny Burstein

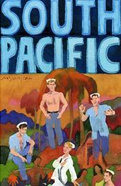

Once upon a time, Danny Burstein was the guy on Broadway who played low-key parts in high-profile productions. In 1995, he starred as Paul, the quiet Jewish groom, in the Roundabout Theater Company's revival of Company, then took over the role of 1st Officer William Murdoch in 1997's Titanic. He acted off-Broadway in A.R. Gurney's Mrs. Farnsworth with Sigourney Weaver and John Lithgow and had a part in the indie film Transamerica. But it wasn't until his side-splitting, Tony-nominated performance as Latin lothario Aldolpho in 2006's The Drowsy Chaperone that Burstein stepped off of the sidelines and showed the full range of his comedic skills. If his current, Tony-nominated turn as Luther Billis in Lincoln Center's smash-hit revival of South Pacific is any indication, he's now the guy who plays scene-stealing parts in high-profile shows. Broadway.com caught up with Burstein in the middle of what looks to be a very good year—even if he's not predicting a Tony victory for himself.

Was the idea of bringing one of the grandest, most beloved musicals in history back to Broadway ever intimidating?

Everyone thinks they know South Pacific and who the characters are. They see the orchestra and hear the beautiful music, and they think it's going to be this big, romantic show. But then you realize, jesus, it's about bigotry! That's a heady thing, especially when you consider that it was written in 1949. Our job was to surprise people with things that they didn't know were in the show.

Luther Billis doesn't feel quite as brutish in your hands.

I got an e-mail from Dena Hammerstein, Jamie Hammerstein's widow, after she saw the show. She said that in so many productions she's seen, Luther was played as very mean and snarky. But I'm flattered when people tell me, "I never really knew how much he cared for Nellie Forbush." At the end, he does something incredibly brave for her, by creating a diversion for Emile de Becque and Lt. Cable to sneak behind enemy lines. He puts his life on the line for her love for Emile. But Luther's largely seen as the Sgt. Bilko of the show.

Is it tempting to just play him for laughs?

It's certainly easy to. It's difficult not wanting to feel the audience laugh at the things you're doing. But comedy is a much more esoteric thing. It's this ballet that you have to dance and still make it feel real and honest.

So comedy really is hard?

Comedy is ridiculously hard. It takes a lot longer to perfect and find every night than pathos. I'll always marvel at people like Nathan Lane. He makes it look easy! His performance in November was just ridiculously inspiring to me. Brooks Ashmanskas and I were talking at the [November] opening party, and the two of us—you know, two character actors—were just bowled over. There are not enough superlatives to describe his performance in that show.

Luther Billis is similar to Aldolpho from The Drowsy Chaperone in that it's a scene-stealing comedic role. Do you think you're carving a niche in these kinds of parts?

I think those are just the demands of those particular roles. Before Drowsy, I was doing an A.R. Gurney play, Mrs. Farnsworth, downtown with Sigourney Weaver and John Lithgow. It's my responsibility to be different. I often find myself at callbacks when I am the complete opposite of everybody else sitting in the room, and I take that as a wonderful challenge. That's what's exciting to me—working hard to find all the quirks and flaws in every character I play. That's what I did with Aldolpho during the entire run of Drowsy, and I'll keep trying to find those in Luther Billis, too.

You played Luther before, right?

When I was 17, at the Keene Summer Theatre in Keene, New Hamspshire, on the campus of Keene State College. Okay, I'll stop saying Keene [laughs]. We were doing seven or eight shows in 11 weeks, something impossible like that. When we weren't acting, we were building the sets, hanging the lights, making the costumes, working backstage. It was an unbelievable experience. But I didn't have much time to work on my character. I'm sure I was just god-awful.

How did that prepare you for an actor's life?

Those non-equity summer stocks are like boot camp for theater. For the whole summer, we got, like, $120, which breaks down to about eight cents an hour. It's a great learning process, because I never felt for a second that I was more important than anyone else in the program. Also, if you can survive one of those crazy summer stocks and find you still want to be an actor, then it's probably for you.

How did you get into acting?

I went to Parsons Junior High School in Queens, where I was lucky to have a teacher who recognized something in me. He said, "You should go to the High School of Performing Arts." And I said, "Great…what's that?" He said they had this difficult auditioning process where I'd have to do three monologues. And I was like, "Okay…what's a monologue?" [Laughs.] The year I auditioned, over 4,000 kids tried out, and around 126 made it in. I got very, very lucky and, at 14, I found myself at the High School of Performing Arts on 46th Street. It completely changed my life.

Was this before or after the movie Fame?

Fame was filmed when I was there, actually. That was the summer after my freshman year, in 1979. I was an extra in dancing-in-the-streets scene and in the lunch-room scene.

You were in the "Hot Lunch Jam"?

Exactly! I was in the "Hot Lunch Jam." That could be my claim to fame, so to speak.

It must've been surreal to be a 14-year-old going to school in Times Square in 1979.

I remember there was a lot of porn back then [laughs]. I was introduced to this world that I didn't even know existed, filled with all of these wonderful extroverts. And I was not that way at all. I was very, very quiet and overwhelmed. Slowly, people came over to me, and I was introduced to this gal who was a senior. She was the most beautiful African-American woman I'd ever seen in my life, and she had the fullest, most beautiful lips I'd ever seen. After our little conversation she said, "We're so happy you're here." And she leaned in and gave me the most perfect kiss on the mouth [laughs], which completely rocked my world! I'm still desperately in love with her. I have no idea what her name is, but I have the perfect image of her in my mind.

Who were your classmates?

Isaac Mizrahi was a senior when I was there. Helen Slater, who went on to become Supergirl, was in my class. There was Erica Gimpel, who played Coco in the Fame TV series. And Kecia Lewis-Evans [formerly of The Drowsy Chaperone and recently in Chicago], weirdly enough. She and I knew each other and did shows together, but we didn't hang out all the time. We connected while doing Drowsy and have become great friends.

What were your first professional gigs?

I went to Queens College and studied with a fellow named Edward M. Greenberg, who'd worked with Richard Rodgers at the Music Theatre of Lincoln Center in the mid-'60s. We did Merrily We Roll Along [in Queens], which was my first production in New York. Afterwards, he invited me to come to St. Louis, where he spent summers working with the St. Louis Municipal Opera. That summer, I did Funny Girl with Juliet Prowse and Larry Kert, and The Music Man, with Jim Dale and Pam Dawber. Ironically, two years ago, Jim Dale and I were in the same category for best featured actor [Dale was nominated for Threepenny Opera; both actors lost to Christian Hoff of Jersey Boys].

What sort of day jobs did you work?

I was a dancing panda on Conan O Brien. I would sing for people dressed as a dog at birthday parties; that's a very long story. I dressed up as a string bean and handed out fliers at Rockefeller Center. I waited tables for three weeks and never did that again. It was a place in Yonkers owned by the mob. I never went back. It was a little too creepy and intense. I'd always run into the most incredibly talented people and they'd tell me how they hadn't worked in two years and were temping at this-and-that place. And I knew that [temping] would just suck the lifeblood out of me. So I kept going to school to get my degree [an MFA in Acting from the University of California San Diego] so I could teach theater if I needed to.

You debuted on Broadway in A Little Hotel on the Side, which was produced by Tony Randall's short-lived repertory company the National Actors Theatre. How did you hook up with him?

I got to know him while doing Around the World in 80 Days in St. Louis around 1986. He'd been talking for 20 years about starting a national repertory theater on Broadway, and how it was a sin that every other major city in the world had one and how the U.S. doesn't treat theater with the respect it deserves. I told him to give me a call if it ever happened. So in 1991, I picked up the phone, and I heard [assumes a Randall-esque tone of voice], "Danny? Tony Randall." I was shocked that he was absolutely true to his word.

You did five shows in two years, which is impressive by Broadway standards.

It gave me the opportunity to work with Tony, Jack Klugman and Jerry Stiller—just some wonderful American character actors. I loved them and all the lessons they taught me.

Like what?

They loved the audience so much and didn't look down on them. Plus, they tried to support each other onstage. I asked Jack and Tony why The Odd Couple was so successful, and they said it was because they loved each other so much. When they had guest stars on, they gave it away and let them shine. That made Jack and Tony look better in the end. And it worked for the story, too.

Then you did the Roundabout's revival of Company. What was it like working with Sondheim?

It was unbelievably intimidating. But he is not precious with his material at all. He helps you find what is important in the lyric and the music and helps make you comfortable.

Now that you're a two-time Tony nominee, do you feel you've arrived at some sort of comfort zone in your career?

Who knows? Not really. When I was doing A Little Hotel on the Side, Tony asked me to come to his house to read lines. He had this who-knows-how-many-million-dollar apartment in the Beresford, overlooking Central Park. We worked for three hours, and he walked me to the door and said, "Do you have anything else set up after the show is over?" And I was like, "No, I don't." So he leaned in and said, "It never gets any easier." [Laughs.] Here was 75-year-old Tony Randall telling me that no matter what or where you are, it's a very difficult life. People win Oscars and Tonys and Emmys and then you never hear from them again. It's a strange profession that way.

You're married to Rebecca Luker, who's currently starring as Mrs. Banks in Mary Poppins, and you have two boys from your previous marriage. How do you make family life work when you're performing at night?

My parents live in Queens, so sometimes they take care of the kids. We also have it in our contracts that we can have the boys in our dressing rooms. They've got their video games and their computers, so they're all set. They've basically grown up backstage. They're ridiculously cool with all the people that they meet. John Lithgow really took to them. He sends them signed [children's] books.

What's it like raising kids in the city these days?

I'm a little more nervous than my parents were, or maybe should have been. During The Drowsy Chaperone, I did let my kids walk between theaters, since it was only a matter of two or three blocks. But they're great kids, very smart and very savvy. Jack Klugman once said to me, "There's kids and there's everything else." I believe that. Anything else pales in comparison to my family.

What do you do during days off?

We have a house in Pennsylvania. Rebecca loves to cook. I love to grill. That's what guys do when they're out there. They grill steaks or chicken or whatever. It's so beautiful and idyllic. We're on a little lake. I go fishing. That's the one thing in my life that is just completely Zen. I throw the line out there, wait for the fish to bite, think about nothing else and three hours have passed! It's great to get away from all the hustle and bustle of our daily lives.

Surely that comes in handy during "awards season." How do you feel approaching all this a second time around?

When I got my first nomination for Drowsy, [the late Actors' Equity President] Patrick Quinn said to me, "Enjoy every moment." So I went to Radio City, and I had the time of my life. I didn't think I was going to win, and was like, "This is the frickin' Tony Awards!" I'm trying to keep that in mind now.

Do you think you're going to win?

No. People ask me if I'm going to prepare something. I'm just going to go and have a great time. That's it. That's all. Whatever happens, happens. I don't want to be overly excited, and I don't want to be overly disappointed. I just don't want to give it that much thought.

Doesn't that require an extra-strength Zen-like approach?

But as a kid, this was never my goal.

You never did the acceptance-speech-in-front-of-the-mirror thing?

Not really. If it happens, it'll be great. Even if doesn't, it'll be great. It's all a great pat on the back, and it feels nice. At the end of the day, all that matters is that I show up at work and do my best.

See Danny Burstein in South Pacific at the Vivian Beaumont Theatre.

Related Shows

Star Files

Articles Trending Now

- Curtain Up on George Clooney in Good Night, and Good Luck on Broadway

- Odds & Ends: Dorian Gray Star Sarah Snook and Glengarry's Kieran Culkin Have a Succession Reunion on Broadway and More

- Molly Osborne Is Making Her Broadway Debut as the Desdemona to Denzel Washington's Othello—Maybe Someday She'll Believe It