Tony Nominee Enda Walsh on How Writing Once Lightened His Soul

About the author:

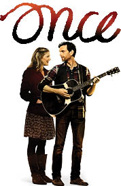

Irish-born writer Enda Walsh made his name with dark, arresting plays such as Misterman and Bedbound, as well as the screenplay for Hunger, which centered on the life and death of IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands. By his own admission, Walsh’s super-serious resume made him “a very peculiar choice” to adapt the indie movie musical Once for the stage. And yet Walsh managed to find exactly the right tone for this unlikely romance between a Dublin singer-songwriter and a Czech-born single mom—and he now finds himself in the running for a 2012 Best Book Tony Award. Broadway.com asked the London-based playwright to reflect on his Broadway success and why he turned out to be a perfect match for Once.

![]()

I’m not altogether sure how I arrived here. Broadway, I mean. At least I can’t remember for certain how Once came about and how I came to be attached to it.

Agents were called, I was called, producers badgered me, John Tiffany (our director) said it might be fun, a room was booked in London for two days in October 2010—and that was it, really.

It was all a bit of a blur, but me, John and Martin Lowe (our musical director) sat in that room in London with two very good actors and read John Carney’s screenplay and sang Glen and Marketa’s songs. Whatever skepticism I had coming into those two days pretty much evaporated when I heard that music and we began to discuss how we might stage this piece.

I was a very peculiar choice to work on this. My work is usually pretty dark, I suppose, and I’m not too sure why that is—but it is what it is—and I’ve been very fortunate over the years that enough people around the world want to produce my work. But I am a slave to all story, whether dark or light, and my instincts were pulling me towards this delicate love story, which I felt would really lighten my soul—would somehow reaffirm for me the potential of the individual to do some good. I think I really needed to be involved in Once, to be honest, and it was good to be making it with friends I love and admire.

Writing a play, for me, is about getting out of the way of the characters, allowing them find the story themselves and not trying to feel like it’s authored in any way. The story of Once existed in movie form but needed its own stage style and also its own specific stage language and pace. Really the key to that was the “Girl” character, who on page one became the driving force, the idiosyncratic swagger of the piece, the person who would change everything.

Anything I have ever written has been about characters finding a voice, or finding clarity in their lives. It’s a very tiny, delicate thing but it can become a powerful theme in the theater—it speaks loudly in those places.

The deal, always, with Once was to make an ensemble piece of theater where you are watching not just two but 13 people’s lives change. They change in small ways, but in the scale of their own lives, they are big.

And yet they are transformed by a young woman who seems more “stopped” than they are. She changes lives—but she can’t start to change her own. That felt quietly tragic.

There’s a lot of comedy and bluster in Once, but sub-textually it’s always a little lonely and inarticulate. We lucked out in finding two lost souls in Steve Kazee and Cristin Milioti. When they don’t speak, they speak to us most clearly of what it is to be people in the world. We’re all sort of blindly walking about and trying to somehow make our way without getting too hurt.

This has been the most joyous process. It has been so utterly unexpected. I think we all feel very lucky to have stumbled on something so rare.