Sharr White on Vulnerability, Mortality & the Dark Inspiration Behind His New Drama The Other Place

About the author:

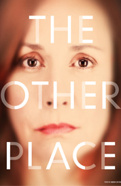

Sharr White began writing plays more than 15 years ago, after earning an M.F.A. from the graduate acting program at American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco. This former aspiring actor now divides his time between playwriting, a fulltime job as a fashion advertising copywriter and raising two sons with his wife in the picturesque Hudson River town of Cold Spring, NY. White is now making his Broadway debut with Manhattan Theatre Club's production of his mysterious and moving drama The Other Place, starring three-time Emmy Award winner Laurie Metcalf and directed by Joe Mantello. While prepping for a January 10 opening night at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, he took time to write about the inspiration behind his breakthrough play for Broadway.com.

![]()

A particular feature of the very smart people in my life is that they think their sheer intelligence can protect them from all manner of harm. It’s a beautiful, yet very vulnerable form of arrogance. (A note to the very smart people I love whom I’m about to mention: I’m not calling you arrogant…just your sense of invulnerability).

My father, for instance, who is a professor of biophysics and physiology, often comforted my boyhood fears of the natural world with soothing scientific explanations, as if very real dangers could be rendered harmless simply by holding an enthusiastic understanding of them: lightning is just static electricity, he would tell me; or heat stroke is just a matter of the proteins in your brain becoming denatured—like fried egg whites; or my favorite, that fascinatingly, spider venom works by destroying the base structure of your cellular membranes, causing massive local hemorrhaging, thus allowing the insides of victims to be sucked out "like a milkshake." Nothing to be afraid of.

And then there’s my brother, with his degree in astrophysics from Berkeley, who often calmed my fears regarding his various adrenalized adventures by telling me that his years of studying how things move on a micro and macro level gave him an edge of safety when it came to things like, for instance, backcountry snowpack, fine ice crystals and gravity. (Yet all his knowledge did not grant him immunity from the laws of physics the day he was caught in an avalanche—yes, miraculously, he lived.)

So when I first set out to write a story about a woman who finds her world crumbling around her, it felt right that I should cut her from this same cloth. When we first meet her, Juliana, the protagonist (or is she the antagonist?) in my play The Other Place, is the embodiment of this fragile arrogance of intelligence. She is by any measure one of the smartest people on earth: witty, sharp, sexy, aggressive and self-assured. And yet because so much of herself hinges on her estimation of her great mind, she also exists in a terrible state of vulnerability. Take her mind away—even a little bit of it—and what does she have left?

Several years ago the wonderful Salt Lake City actor Paul Kiernan told me that at heart my plays are about lost people who become found. This was crucial for me to know while building Juliana’s character and circumstances. Juliana’s journey through The Other Place needed to be one in which, bit by bit, everything she knows is stripped away. I found that as I worked, Juliana’s central action became, over and over, fighting to hold on; to convince people that what she was seeing, and hearing, and doing was the correct version of reality. From her perspective, how could it not be, given her intelligence? One of the issues that began arising was that this action began to create a sort of feedback loop; her aggressive self-assuredness only grew as she fought to hold on to her version of reality.

Because of the strength of Juliana’s fight, she only began to falter once I’d stripped her down to almost nothing. She literally had to lose everything in order to be able to admit that she was ill. And because of the stock that she’s placed in her own superiority, in her own intelligence and understanding of the world, this admission becomes her final blow. At last she’s vulnerable enough to be found. And she is. She’s cared for, selflessly and quietly, the way—I hope—one day I might be cared for. The way we should all be lucky enough to be cared for.

My favorite definition of mortality is that it is The state of being subject to death. We so often enshrine people who, through their displays of intelligence, or daring-do, or physical skill, seem to refute the idea that they could ever become one of Death’s subjects. This refutation is what Juliana displays at the top of The Other Place. It is the inevitability of mortality that she at long last admits to, in the end.

Certainly my father and brother have offered me the same through their rational explanations of the world. Or if not a refutation, then at least the idea that by understanding the molecular processes behind death, though death itself be not banished...the fear of it will. Death becomes, on a purely scientific level, a few inevitable numbers. Just math. My father has a poster on a corkboard in the house he shares with my stepmother. It says “I have so much to do and I am so behind that I will never die." How Juliana, and me, and all of us, wish that were true.