Tony-Winning Curious Incident Playwright Simon Stephens on the Danger of Words and Why Awards Don't Matter

Newly minted Tony winner Simon Stephens is a prolific playwright with two shows on the New York stage at the moment: Best Play winner The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time and off-Broadway’s Heisenberg. His other works include the gritty Punk Rock, Port, Wastwater, Harper Regan, Pornography, One Minute, Carmen Disruption, the Olivier-winning On the Shore of the Wide World and many, many more. Stephens recently invited Broadway.com to his downtown hotel room (with an awesome view) to talk process, preparation and Chekhov.

What time of day do you write?

I tend to do a normal working day that’s built around the family. I take my kids to school then go up to my office, where I work from 10 to five. I think you only really need to do about four hours a day of work as a playwright. Our work is not defined by a word count. It’s not like being a novelist where you need to write 10,000 words a day or whatever.

Describe your muse.

My muse is my wife and my children. Not necessarily because my wife is so beautiful that I just gaze toward her. I mean I write plays about people being shot in the head. It’s because this is my job. They ground me. She reminds me to have fun and not get jumpy. She takes the piss out of me. The kids, too. I always think the subject of theater is what it is to be human. There’s no better way to understand human beings than to make one and watch it grow. I’ve been a much better writer since my children were born.

What’s the first thing you do when you sit down to write?

Read the entire Internet.

How long do you procrastinate before you get down to work?

Six hours. And then there will be like two hours left before I have to go pick the kids up, and I’ll be like, “F*ck! I haven’t written anything!” Then I’ll write something really good because I’ve got no time left. Although that’s presented as a joke, there’s something true in it.

What’s something to keep in mind when adapting a work?

Drama concerns itself only with the things people do to one another. Novelists often concern themselves with the things people remember, think, observe or whatever. You have to release universes of thought and feeling through action. That’s the job of a dramatist. That’s it. Subsequently, our work is not linguistic; it’s behavioral. I remember talking to [Curious Incident novelist] Mark Haddon about the difference between prose and drama. He said, “The thing about Curious Incident is that the funniest line in the play with the loudest reaction every performance comes from the line, “OK.” It’s true. Mark said, “There is no way that the word ‘OK’ would ever be the funniest line in a novel.” It just doesn’t work like that.

What play changed your life?

Do you get your best work done as the day is winding down?

I think the energy of a ticking clock can be really useful. I do a lot of exercises to timers. It’s hard to say what’s good writing when you’re working on a play: Sometimes it’s writing good dialogue, but sometimes it’s making good structural decisions like deciding how many scenes you’re going to put in the play. Those can be the real epiphany moments. With Curious Incident, the decision to use Siobhan as the narrator—I swear I had that idea while walking down the street. It was a classic writer’s epiphany. But then epiphanies come as a product of work; they don’t come from the ether. You do a shitload of work and then they come.

What essential items do you like to have on hand when you’re writing?

I don’t really have anything but my computer. I can write anywhere and in any circumstance. It kind of staggers my wife.

How much planning do you do for a piece?

I’m a thorough planner. I don’t write from nothing onto the page. There are five stages of the writing process for me. There’s a lengthy period of months and months of mulling. I move from what Peter Brook describes as “a formless hunch” to starting work on a play. I’ve got to go very slowly with it. The slowness is key. Then I will start researching—reading around the subject I’m writing about. I might look at art, listen to music, watch movies or interview people—to just start filling up the sponge. From the research comes a lot of note-taking: I’ll do exercises to start generating material, and that will take a month or so. Then I’ll start to land on the characters in the play—what they want, what’s stopping them from getting what they want. After that, I’ll figure out how many scenes the play has and how many characters are in each scene. Then the process of writing is like painting by numbers. I really love that because it allows me to work very quickly. The tension between slowness and speed is really useful.

How do you celebrate when you finish a draft?

I always embark on every play with the absolute certainty that I won’t write it. I think I’ve already written every play I’m ever going to write, and doing another one is a pathetic act of self-flagellation. That’s how I start, so if I manage to get to the end of it, there’s always a moment of [big sigh of relief]. I tidy the office. That’s my celebration.

What’s the nitty gritty hard work of being a playwright that no one ever told you?

There are lots of hard things about being a playwright, but in Britain there are a lot of playwrights and a lot of support and mentoring. I think it goes back to that thing that it’s not linguistic. It’s really about action. If anything can ruin a play, it’s words.

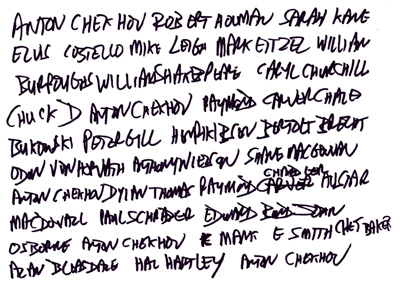

What writers inspire you?

What should aspiring writers know, do or see?

They should know that the career is utterly irrelevant. What matters is the work. The notion of [the Tony Awards] blows my f*cking mind, and it's flattering, but it’s dangerous because it’s a distraction. Curious Incident works as a piece of theater—that’s the thing to cherish. The career is really seductive when you’re starting out, but it doesn’t f*cking matter. The process of writing today is exactly the same as it was when I was working as a barman and thousands of pounds in debt with my parents telling me I was never going to make it as a writer. The stuff surrounding the writing is different, but the writing is the same. That’s important for young writers to know. It’s not like there’s a magic door that you go through and then you’re a successful playwright. You’ve got to do the work. That’s what you need to know. What they should do is just f*cking write. Know that you’ll be shit, and the first few plays will be shit. But keep writing—maybe play number 10 will be good. Also, see anything by Anton Chekhov.

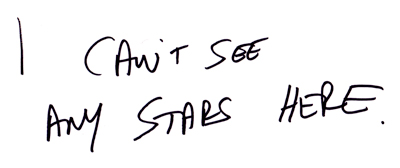

What’s your favorite line in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time?