Guards at the Taj Playwright Rajiv Joseph on Comic Book Inspiration and Writing During the Dim Hours

Rajiv Joseph’s Guards at the Taj, which recently extended at the Atlantic Theater Company, is an unexpected mix of brutality, comedy and suspense. He is perhaps best known for his play Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo, a 2010 Pulitzer finalist that starred Robin Williams on Broadway. His other works include Mr. Wolf, The Lake Effect, Huck and Holden, Gruesome Playground Injuries, Animals Out of Paper, The Monster at the Door and The North Pool. Joseph recently invited Broadway.com into his peaceful Brooklyn studio apartment, where he writes standing up in his kitchen while consuming copious amounts of hot water and lemon. Read on to learn more about his process.

What’s the first thing you do when you sit down to write?

It depends. I don’t light a candle. Jack Kerouac did—he would light a candle before he wrote. Oftentimes, I write in my journal first. I keep a pretty intense journal—intense meaning I’m pretty regular about it, and I have been since I was about 22. Now I’m 41. That’s a good way to get the juices flowing.

What do you write about in your journal?

It’s just personal stuff, but it’s not probing. It’s what I did yesterday or the dream I had last night or questions I have about whatever I’m working on. One of my favorite things to do is put a play away for maybe six months to a year and then when I’m ready to start working on it again—before I read it again—I write a document about what I think the play is about, what I want it to be about, the problems that I think exist and the new ideas that I think I can bring to it. It’s funny how much you forget about a piece, so I write those things down because I won’t be in this headspace again.

What essential items do you like to have on hand when you write?

I don’t have any totems. I write on a computer, but I also write on legal pads. I find if I’m struggling with a piece, I’ll write longhand. I tend to find a lot of ideas that way.

When did you know you wanted to be a playwright?

I went to grad school to be a screenwriter. At NYU they made us take both screenwriting and playwriting the first year. I liked the playwriting classes and I started seeing plays. I hadn’t really seen plays before. I had grown up seeing musicals, which I loved and do love, but I hadn’t really gone to any contemporary straight plays. I started seeing those, and it changed my life.

Did you always want to be a writer?

I always wrote, but it wasn’t really on my mind so much to be a writer. I never thought of it as a career option growing up. When I got to college, I wanted to take an intro to fiction class, but I didn’t want to be a creative writing major. You had to major in it to take this course. Everyone was like, “Just declare it as your major and change it later.” So I went into the dean’s office to declare it thinking it would be quick paperwork. He sat me down and was like, “Why do you want to be a writer?” I just wanted to be in the class! Then he started talking about Raymond Carver and What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. It was bewitching. He took so much time just to talk about literature with me. The die had been cast.

What play changed your life?

What’s the best advice about writing you’ve received?

One of my best teachers, Charlie Purpura, told me that a terrible finished script is always better than a half-finished one.

What time of day do you get your best work done?

The dim hours. Early morning or late at night. When I was in graduate school, I only wrote at night. I wrote through the night and didn’t sleep much. Now I have a little more freedom, but I also have more work to do. I find I work best when I’m away from New York. When I’m someplace else like in a hotel room. I work great in hotel rooms, and I love them.

What inspired Guards at the Taj?

It was inspired by some stories I was told as a kid when I visited the Taj Mahal for the first time. My aunt told me those stories and they stayed with me my whole life. There was a whole swath of Indian history about the Mughal Empire that I learned as a child because my uncle would send me comic books from India that were about the Mughals. I had a thought for a long time that I wanted to write a play about the Taj Mahal. I started writing one about 10 years ago and it was a really large piece with 10 characters and four acts. It was a real mess. I decided to stop writing it because it was terrible. When I looked back on it, the only two characters that were interesting were the smallest ones, which were the two guards. They were just kind of sitting there and watching everything happen. That’s where this came from.

How long did it take you to write the play?

Not including that first failed attempt, a little less than three years.

What motivates you?

The short answer is deadlines. The longer answer is that at this point I want audiences to respond in a certain way to the work. As I’m going forward, I find I’m veering toward more political stuff. I’ve written politically in the past but it always seems to me that that’s where the ideas are, so that’s important to me.

What’s the greatest lesson you’ve learned from your collaborators?

When I was working on Bengal Tiger with Moisés Kaufman, he said actors are the most underutilized resource in theater. He works from a very holistic, collaborative place, and he would bring the actors into the discussion about the dramaturgy of the play in a real way. Actors are investing so much in these lines that I’ve written, so it behooves me to ask them as many questions as I can and listen to them with great attention. It will only help. I trust [Guards at the Taj stars] Arian [Moayed] and Omar [Metwally] as much as I trust anyone in this regard. When they tell me something—even if I don’t agree with it—I try to consider it as deeply as possible. More often than not, I find myself figuring something out with it and the play improves.

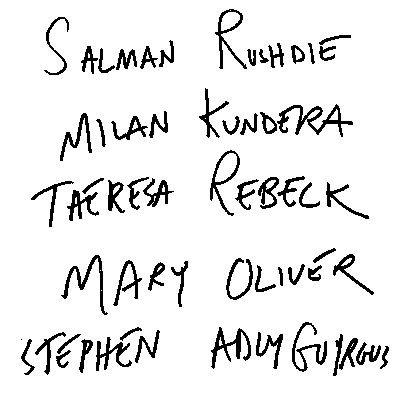

What writers inspire you?

This play is so surprising. Tell me about creating some of those twists and turms.

The play is unexpected because I wrote so many versions of it. I think that if a story comes very easily to me the first time I’m writing it, it’s because it’s predictable. I’ve thought of it, so you’re going to think of it. But if I spend three years designing the ins and outs of a plot and the character turns, chances are—hopefully—I’m going to be a little bit ahead of the audience because they are just sitting down for the first time.

What’s your advice to aspiring playwrights?

This is not gospel, but I think they should keep a journal. As an exercise, they should find something political and try to make it theatrical. That’s hard. It’s not something that comes readily, and it’s not something that’s in everyone’s aesthetic, so it’s certainly not a prescriptive thing. But these are things that help me and cause me to have certain breakthroughs.

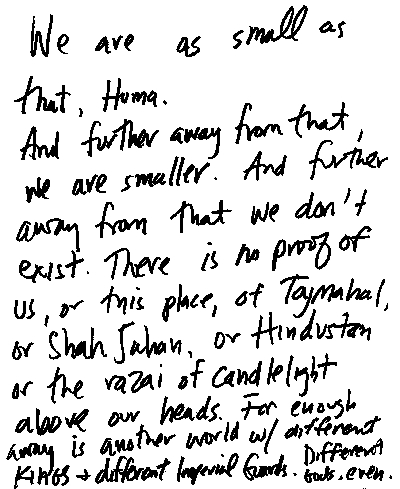

What’s your favorite line in Guards at the Taj?

Related Shows

Articles Trending Now

- 2025 Drama League Nominations Announced; Idina Menzel, Helen J Shen, Nicole Scherzinger, Lea Salonga and More Up for Awards

- Tony Winners Wendell Pierce and Sarah Paulson Will Announce 2025 Tony Nominations

- Redwood, Starring Idina Menzel, Will Release an Original Broadway Cast Recording in May; Debut Track Out Today