Sylvia Playwright A.R. Gurney on Drawing Inspiration from Dogs, Ethel Merman and His 'Fading Culture'

A.R. Gurney is one of the most prolific and often produced playwrights working today. His many works include Love Letters, The Dining Room, Sweet Sue, The Cocktail Hour and Sylvia, which is currently playing at Broadway’s Cort Theatre with Annaleigh Ashford in the title role. Gurney recently moved into a spacious new apartment on the Upper West Side and invited Broadway.com over to talk about dogs (his most recent one, Bill, died a few months ago), Broadway and his "bourgeois habits."

What time of day do you get your best work done?

I’m getting a little lazy now, but I’m normally up by 8:30 and at my desk by 9. I write in the morning, have lunch, and then write a little in the afternoon—just going over what I’ve written but not writing with any kind of the intensity that I can muster up in the morning. I’ve been doing this for 40 years. I’ve always been a morning writer.

What essential items do you like to have on hand when you write?

Nothing. It took me a little while to learn first how to use a typewriter—I mean I always could type, but I never thought I would write creative stuff on the typewriter. Later I taught myself the computer.

What play changed your life?

What’s the first thing you do when you sit down to write?

That depends. I try, if I’m in the middle of something, to have left the ball in the air, so when I come back, I know exactly where I am and how I can catch the ball.

Is it hard to leave the ball in the air?

No. It’s rather easy. Writing is hard; it gets lonely. While I like to do it and there are moments of great pleasure, I’m glad to get away from it. But then I’m eager to return to it.

What inspired Sylvia?

My dog! My wife Molly teaches in town, and we bought this house in the country. I liked to stay up there and at that time. I did a lot of gardening and fixing up of the house, but I missed her. I had made myself a peanut butter sandwich for lunch and read this ad in the local paper about a Lab puppy. I always liked Labradors, so I just thought I’d go over and look at it. Well, I came home with it. My wife said, “For god's sake! No more dogs!” I knew I was in trouble, but I had already fallen for this dog. I said, “I don’t think I can give this up.” The lines from the play are real. She said: “I won’t walk it. I won’t feed it. I won’t pat it. I won’t have anything to do with it.” One time I got quite sick with the flu, and she said, “Sorry, you’re going to have to get up and walk that dog.” Then she softened a bit, just as Julie [White] does at the end of the play.

What are some of your dog’s names over the years?

Porgy, Sambo (like Little Black Sambo—that was very racist; it was a long time ago), Alice was the first female dog I had, then I had a great rescue dog called Joe—even my wife adored him— and Snoozer, who is a character in a play of mine, and ultimately the last one I had is Bill. Most of them had human names.

What’s the best piece of advice you ever received about writing?

To continue the habit. Don’t walk away from it even though you hit a slump or you don’t think you have anything else to tell the world. I’ve certainly felt that many times. Sit down and work even if you're thinking, “This is going to be a useless morning and nothing is going to work,” something does. I’d say just stick to your last. Isn’t there an old expression, the workman sticks to his last? The very process of writing words can cause creative things to happen that you didn’t think were there.

You are one of the most prolific playwrights working today. Do you attribute that to your persistence?

I think so. You could say I can attribute it to my stupidly bourgeois habits.

What drives you to write now that’s different from when you were first starting out?

I always write about where I am. I wrote plays about falling in love and how to deal with kids. When my kids started to leave the nest, I wrote plays about that. I try to write as much as I can about my own experiences. I’m getting old and I’m writing about how it feels to get old. I’m just starting another one, but I won’t tell you what that’s about.

Do you keep a notebook?

I used to keep a notebook, but I don’t now. If you looked at my computer, there are sort of half-written plays with great titles, which never went anywhere.

When you’re starting to write a play, do you make an outline?

No. I start with the play. I think I want to have some place to go, so I don’t just write about two people talking or whatever it is. It might end in a very different way than I thought it would. I remember with Love Letters, I had no idea where it was going, I knew I had a pretty good story because I had two very different characters who were fascinated with each other, but then suddenly towards the end, I realized I had to kill her off. When I wrote the last scene, I cried—tears were dripping down my cheeks. I never expected it to go that way, but it had to go that way.

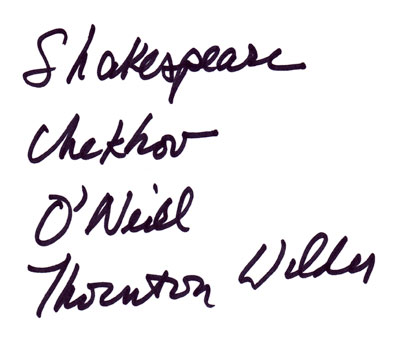

What playwrights inspire you?

How do you feel about being so closely associated with WASP culture?

I used to think it was slightly pejorative. It meant snooty, alcoholic and intolerant. I used to think I wasn’t writing just about WASPs: I’m writing about issues people can understand and identify with. Then I began to realize that I was writing about my own culture; I didn’t realize how parochial my own culture was. I thought I was writing about the heart of American behavior. Not at all! Not everyone has dining rooms! I kind of woke up to the fact that I was exploring my own culture and how it was fading. Responding to that sense of obsolescence and that was really my theme.

What does it mean to you to have Sylvia on Broadway?

This is my third play on Broadway. It’s been wonderful: I’ve been working with the top people—designers, directors, actors. Partly because we’re doing a play that I’ve seen done many times, there hasn’t been that much for me to do. A lot of playwrights like to sit on rehearsals, and normally I do if it’s a new play. It’s impressive for me to see this play emerge on Broadway with these terrific people.

You are known for loving musicals. Why don’t you write them?

I do love them and I used to write them. The first time I went to New York—I was at a boarding school and my father got me tickets to Annie Get Your Gun with Merman. It just blew me away. Not only because she was so funny; she pretends she’s a Western kind of Okie, but she’s a New York girl from the beginning, middle and end. Suddenly, all I wanted to do was write musicals. I went to Williams College—Stephen Sondheim wrote the musicals there, but he graduated two years before I did. So I said, “I’m here, I can do that!” I certainly couldn’t write music, but I found people to write the music with me. The Korean War was on when I graduated. I became an officer on a giant aircraft carrier. We had the ship’s orchestra, and I wrote musicals. I loved it. Because of that, I went to Yale School of Drama. But then for some reason, I ran out of steam. I cut my teeth doing musicals, but I never wrote another musical. Oh, I did write one! A Cole Porter take-off, which didn’t work.

What do you think all aspiring playwrights should do or see or read?

Aspiring playwrights should write as much as you can. See as many plays of different types as you can. I know it’s not cheap to go to the theater these days, but you don’t have to go to Broadway. Read Ibsen, read Chekhov, see how the pros did it. Your generation grew up on television; I grew up on radio, and radio taught me the power of dialogue—how much of a story you can tell just through talk. Your generation is much more aware of the visual possibilities, but television tends to be reactive, the television camera tends to go to the person who’s listening and not the person who’s talking. Sometimes it affects younger playwrights because they’re so good at dialogue, but the television influence has suggested to them that plays don’t have to have that forward action that they must have. I think that you’ve got to learn that.

What's your favorite line in Sylvia?