Quiara Alegria Hudes on Why She Wrote Daphne's Dive & How Lin-Manuel Miranda Is Like Seinfeld's Kramer

(Photo: Caitlin McNaney)

Quiara Alegría Hudes is an award-winning writer whose works include the Tony-winning musical In the Heights (for which she wrote the book), the children's musical Barrio Grrrl! and the plays Elliot, A Soldier's Fugue, 26 Miles, Yemaya's Belly and Water By the Spoonful, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2012. Born and raised in Philadelphia, where she has set many of her works, Hudes lives in a spacious Washington Heights apartment with breathtaking views of the Hudson River. The scribe recently invited Broadway.com over for a chat about the inspiration for off-Broadway's Daphne’s Dive, her collaboration with director Thomas Kail, her neighbor and pal Lin-Manuel Miranda and how music infuses her work.

What's the first thing you do when you sit down to write?

I check my email and read the news. I also like to read interviews with playwrights or other authors, so a favorite is The Paris Review. That loosens me up and warms me up. I also listen to music during that time. Oftentimes it's the playlist for the play I'm writing.

At what point in your process do you create a playlist?

Very early. I have it before I start writing. There's a long process of percolation for me before I type a word, and during that time, the music will find me.

How long is your percolation process?

The longest one I've had is about 10 years and the shortest one I've had is maybe four or five months.

How long was it for Daphne’s Dive?

This one was maybe sixth months. Some of the notions in it I've lived with for a very, very long time, though. The character of Jenn is one that has always been in my mind and was never attached to a story or a play. She has been with me for a decade.

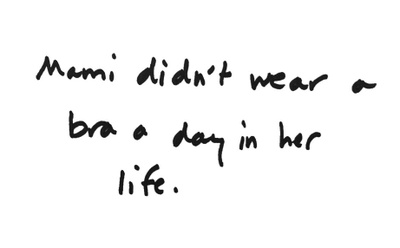

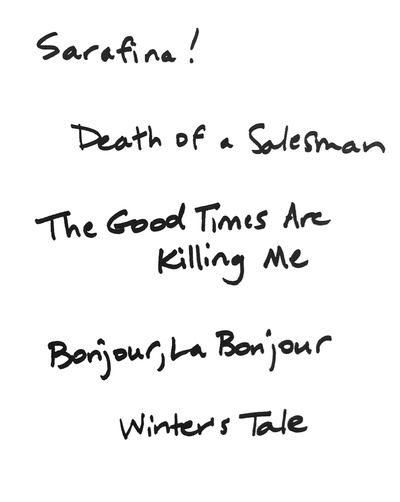

What plays changed your life?

What sparked the idea for Daphne's Dive?

The main one is the location. After work on [the Elliot trilogy], which was very intense, I wanted a sense of relaxation. All three of the plays in the trilogy had a lot of scenes and at a certain point, it felt like my job was almost as a construction worker to make sure those scenes were structurally sound. I wanted to have longer scenes that had a little bit of breath to them. I thought a bar was the perfect setting: My stepfather owned some bars in Philadelphia, where I used to hang out after school, so it was a setting I was familiar with. I loved the bar as the hub of local news amongst the neighbors—from there the voices just started coming to me.

How do you feel this play is different from your other work?

I have a strange relationship with nostalgia because I have been accused by my harshest critics about being a little indulgent and nostalgic. And yet oral storytelling is essential to a culture of survival. So, this was me taking on that criticism and also what interests me: what kind of stories are told about hardships—the way they choose to curate and remember their lives. I was also doing an experiment with time. I wanted each scene to feel very full. This play has five scenes and there is no continuation at the end of each one; we jump forward in time. You feast and then you famine.

You studied music and it clearly is a big part of your life. How did you want it to be part of this piece?

I had been listening to the pianist Michel Camilo since I was a teenager. He's virtuosic and his music is extremely joyous. This [play has] a community that is dealing with many challenges, and there's something about placing that in the context of joyous music and asking how do we continue to find joy even when the world is rallying really hard against that emotion. I imagined [Michel Camilo] as a character: He is the pianist that lives upstairs. After I wrote the play, I reached out to him, though I had never met him. I said "Mr. Camilo, may I be so presumptuous to ask you to consider composing the music for this play?" He said yes. His music was the playlist for this play and then it became the score.

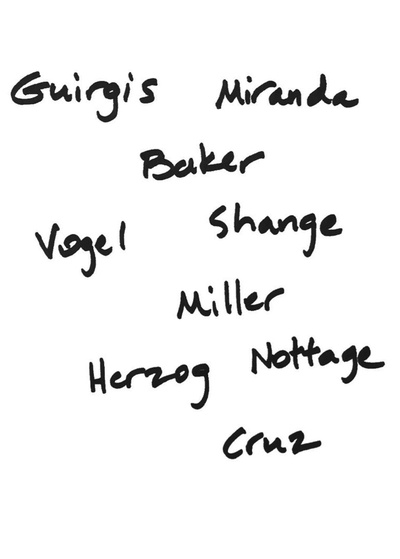

Which writers inspire you?

This is another collaboration with [director] Tommy Kail. How does he challenge you?

He has a very keen eye for detail, so he challenges me sometimes on the syllabic level. He'll say, "I think one more syllable there is what you need rhythmically." He knows I think rhythmically, so he engages me on that level, and he can also see the piece at a real distance.

What essential items do you like to have on hand when you write?

Well, I have my mugs. I always have my music, and as you can see around my desk, I have some old family photographs and pictures up. One of my favorites is a postcard of the second to last painting that Pablo Picasso did because it's so naïve. I love that sense of returning to a very naive place at the end of a masterful life. I look at it every day.

What's the best piece of advice you've ever received about writing?

It was probably from Paula Vogel, who said to me that writing is a muscle and it gets stronger. Then on the flip side is an interview I read with Edward P. Jones, the novelist, who said, “You're never a writer; you're always becoming a writer.” So it's in your muscles and it gets stronger, but you have to reinvent it each time.

How has what drives you to write changed over the years?

My mom looked me in the eye and said, “This is our history: it's not written down, it's not recorded, it could disappear.” So she gave me a task to do, and I would not have done that task if it did not resonate deeply within my core. Sometimes I wish I could just write plays that don't have that social context of what happens if this particular story never gets told, but I haven't been able to escape that yet. There's still more to say.

What's the most common question you get from young writers?

“What internships should I get that will make me a playwright?” And, of course, there is no internship that makes someone a playwright. Making it as a playwright is this funny thing. I had a day in my life where I made it as a playwright, maybe even two. But then the rest of the days, you just stand up and do the thing.

What was it like to work with Lin-Manuel Miranda?

It was one of the bigger challenges I've been served up in my writing career, which was to take someone else's vision and make it even more itself. Lin and I have a real commonality: We have common values and history that we drew from together. I believe so much in his vision.

Doesn’t he live in this building?

He lives downstairs. We're very good friends, and when you asked earlier what my writing morning looks like, I should have mentioned that Lin will often come up for half an hour and have coffee. We'll chat about what's going on in our lives, and then I head to my writing desk. It’s nice to have that kind of Kramer-like character in my life.

What's the nitty-gritty hard work of being a playwright that no one ever told you?

Dealing with anxiety when it goes public and also maintaining clarity. When you're in previews, you have to keep writing; it's a really important part of the process. But that's when all these gremlins and ego stuff starts to get in my way—I get scared and feel exposed. I feel like I'm always on the precipice of ultimate humiliation.

What is something you think all aspiring or new writers should do or see or read?

The daily practice of writing: To find that habit and do it. The other thing that was really wonderful for me was to find a community of writers.

A lot of aspiring writers struggle with the balance of having a life, paying their bills and staying at it. Do you have any advice for them?

I think life experience is the top of the priority list to become a playwright. I don't prioritize working in the theater much. Make some money and have interesting life experiences—whether that’s being a teacher or building a house or tending a bar—keep those bills paid and write about life.

What's your favorite line in Daphne's Dive?