Michael C. Hall on Shaving His Arms, Being Part of David Bowie's 'Posthumous Homecoming' & Making His London Stage Debut in Lazarus

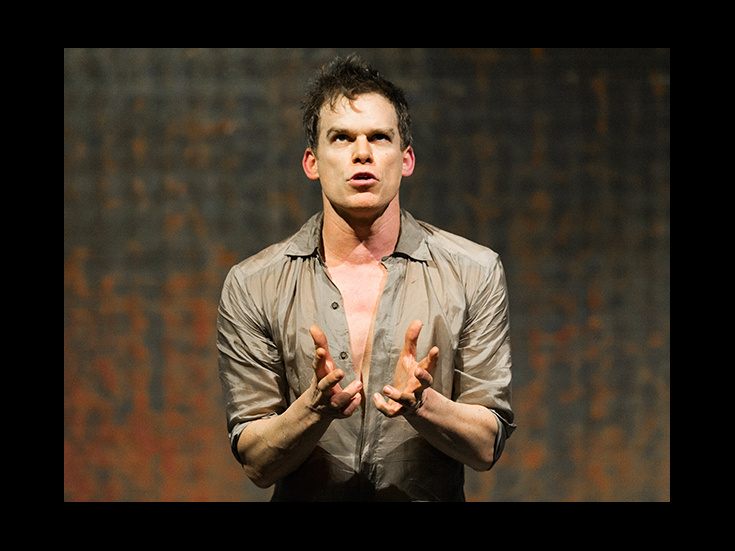

(Photo: Jan Versweyveld)

Michael C. Hall is known for his award-winning work on TV’s Six Feet Under and Dexter but has been returning to the theater with increasing regularity of late, whether as one of Broadway’s Hedwigs or leading the starry ensemble of Will Eno’s The Realistic Joneses. He is currently making his London stage debut reprising the iconic part of Thomas Newton in director Ivo van Hove’s production of Lazarus. The David Bowie-scored musical, co-written by Bowie and Enda Walsh, is now previewing prior to a November 8 opening at the King’s Cross Theatre, so Hall was well placed to talk about picking up a part he played to acclaim off-Broadway last season.

What is it like returning to the role of the resident alien Thomas Newton after the better part of a year away?

This is something I’ve never really done before, and I was very curious as to how it would feel. What I’ve found is that the piece has been recontextualized doing it here in London and also, of course, by our performing it and [the audience] seeing it informed by David [Bowie’s] passing. [Bowie died in January, not long before the end of the off-Broadway run.]

Did you expect an onward life for the production, once it finished at New York Theatre Workshop?

Yeah, from the time of our opening there was talk of it having a life beyond the Workshop and that was something on all of our radars back then. When we did it for the last time [in New York], I very much had the sense that I wasn’t saying goodbye.

How does it feel to have been described in this musical as “Bowie’s representative on earth”?

I suppose it makes sense that someone would make that connection. I mean, talk about something beyond your wildest dreams!

Has the show itself been changed by Bowie’s too-early passing, at the age of 69?

On the surface nothing has changed: we’re still executing the piece that David initiated, and he was very much involved in its development. But inevitably there’s a sense of his presence as it pervades the piece and its message, whether implicit or explicit, is that much more potent now that he’s left us. It’s as if his presence is all the more palpable since he died.

Did you have to prep for the role afresh?

Well, I certainly made sure that I started singing more regularly and that I got the particular songs back in the groove of my voice, and then we had four weeks’ rehearsal to put it back together. A good amount of time had passed, but not so much time that I wasn’t still very pleased to discover that I had it in my muscle memory.

Am I right that you’ve shaved your arms?

I have! That's something I did: nobody requested that. When I look down and see my hairless arms, it looks more like alien flesh to me.

Do you agree with those who find the show's tale of “the man who fell to earth,” to quote the title of the Bowie film that inspired Lazarus, to be “cryptic”?

I feel that for Thomas Newton the piece is arguably all happening within the confines of his head and within the confines of his imagination and that he is not in complete control of those faculties, so the unfolding story and action of the piece are surprising and mysterious to him. If that makes [the show] “cryptic” from night to night, then that surely is appropriate. I’ve resisted the temptation to pin anything down so that I can allow what happens every performance to be continually and newly surprising.

Has there been any confusion about what the audience thinks it’s coming to see—a David Bowie jukebox musical perhaps?

I think there are people who come having no sense of what they’re going to see and inevitably—because this in many cases is known as “the David Bowie musical”—make inferences that are way off base.

On a vocal level, how does this part compare, for instance, with the glam-rock challenges of playing Hedwig?

It’s different. Hedwig is unique and I think from a physical standpoint was as comprehensively challenging as anything I’ve done: vocally, emotionally, cardiovascularly. This, in turn, requires a different kind of concentration insofar as everything is conjured by my character’s experience. And I do have seven numbers. I definitely need to get my rest.

Is it difficult to come down, as it were, after each performance?

It’s draining and exhilarating—an exhilarating drain. I step into the shower and wash off my milk—spoiler alert! [laughs]—and that kind of helps re-set everything. I certainly don’t struggle to fall asleep at night.

Don’t you feel that David Bowie would have totally got the world of Hedwig?

Very much so. I think if you made a list of the people to whom Hedwig owes a debt, Bowie would be first on the list, in terms of the glam sensibility and also the musical sensibility. “The Origin of Love,” which is the seed from which the whole of Hedwig and the Angry Inch grew, sounds like a Bowie song.

Did you revisit the 1976 Nicholas Roeg-directed film that gave rise to Lazarus?

I watched [The Man Who Fell to Earth] for the first time around 2005 and then again when we were in rehearsals in New York and yet again at the London Film Festival here when they had a new print of it. I was perplexed by the film when I first saw it, but it remains of its time in terms of the way it was shot and the drug-fueled atmosphere of the creatives. If nothing else, it’s such a wonderful chance to get an up-close look at Bowie at the height of his powers.

How familiar were you with the London theater?

It’s somewhat new to me, though not entirely. The first time I came [to London] was in eighth grade on a school-sponsored trip with my mother. She managed to get us tickets to the hot musical in town, which was Starlight Express. I remember sitting in the top balcony seriously jetlagged and every time I would start to nod off, these roller skaters would come whizzing by.

Have you long had a desire to appear here on stage?

I always loved the idea of finding a way to work here, and I couldn’t think of a better way to do it than via this sort of posthumous homecoming.

Didn't you make your Broadway debut in a British play?

I was the understudy for Christian Camargo in Skylight [the David Hare play, first seen in New York in 1996], but I never went on. I would just call in at the theater each night at 7 30 and watch The Simpsons. That was the job that got me my Equity card and to sit in that theater and watch [leading man] Michael Gambon stalk that stage remains a highlight of my life: it was so incredible. I did later get to do the part in L.A. with Brian Cox and Laila Robins.

Are you looking to increase the amount of theater you do now that you’re no longer in a TV series?

I never planned to do 13 consecutive seasons of TV, which is what I did with five seasons of Six Feet Under followed by eight of Dexter and I had been acting more or less exclusively onstage before that. It was only when I got the chance to do The Realistic Joneses that I reactivated that love, that appreciation, for the theater and the immediacy of that experience. I certainly like to imagine that there will be further opportunities for me in other mediums, but the theater has always felt like home.

How does it feel to be opening your show on Election Day—and away from home?

I thought it might be odd, but with the internet, everything is so accessible and all the information is right there. I think, too, that Brexit has made the British perhaps less inclined to be pompous about what’s happening in the US. Besides, whatever happens on Tuesday isn’t the ending of something, it’s only the beginning—though I hope not.

Articles Trending Now

- Curtain Up on George Clooney in Good Night, and Good Luck on Broadway

- Odds & Ends: Dorian Gray Star Sarah Snook and Glengarry's Kieran Culkin Have a Succession Reunion on Broadway and More

- Molly Osborne Is Making Her Broadway Debut as the Desdemona to Denzel Washington's Othello—Maybe Someday She'll Believe It