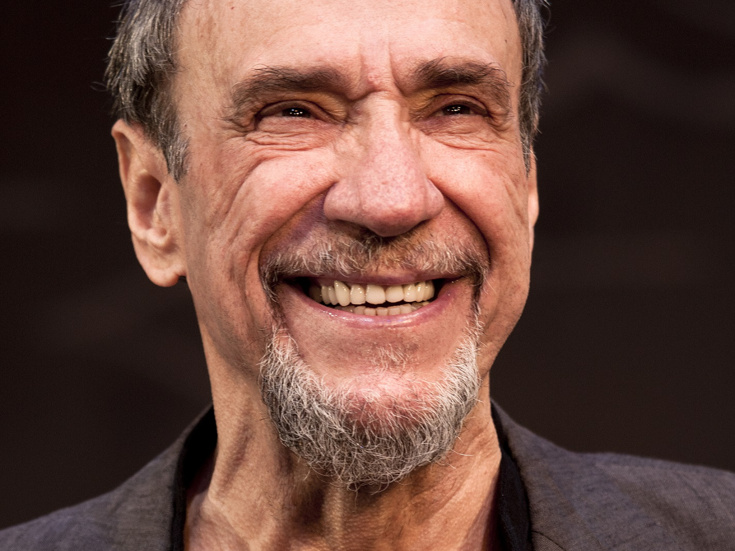

F. Murray Abraham on Returning to the West End in The Mentor, His Homeland Fame & Why He'll Never Retire

(Photo: Simon Annand)

It’s been more than 30 years since F. Murray Abraham won the Oscar for his indelible screen performance as Salieri in Amadeus, since which time he has appeared regularly on stage and screen and had a career-defining role on Homeland as the ever-intriguing CIA baddie Dar Adal. This summer, he can be seen in the West End starring in German writer Daniel Kehlmann’s play The Mentor at the Vaudeville Theatre, so what better time to talk shop with a veteran thesp who has banished the word retirement from his vocabulary.

Are you excited to be back on the London stage, having appeared on the West End 21 years ago in the James Goldman play Tolstoy?

I am, and this really is a wonderful part for me. I can’t wait to get to the theater to show off. I feel about [the part of] Benjamin Rubin pretty much as I did when I played Bottom [in A Midsummer Night’s Dream in New York in 1989]. I don’t often get a chance to be funny, so here I get to show that side of me off and to be pretty dramatic, too. It’s an ideal role.

Were you surprised to find yourself doing a piece written originally in German, though translated by Christopher Hampton?

In fact, Daniel contacted me directly and said, “I had you in mind when I wrote this,” which was interesting given its German origins. He said he would like me to read it, which I did and I liked it and that was just in a rough translation. Afterward, Christopher Hampton brought his own chops to it.

Do you sense a sort of theme in your work, given that the court composer Antonio Salieri was, of course, obsessed with art, and so is Benjamin Rubin, albeit with literature and not music?

I hadn’t thought about it in those terms but that’s entirely true. But isn’t that what you and I are concerned with—what people like us are devoted to? One of the great values of the theater is a communal search for truth: I believe that sincerely. It feels these days as if truth doesn’t exist except in art, so you can understand where these men are coming from.

Salieri’s quest for excellence leads him towards madness and murder—does Benjamin Rubin confront the same demons?

Rubin’s quite different in that he’s so equivocal. You’re never sure whether this character is a wunderkind or a fraud, and I do switch back and forth a few times. I try to destroy the young writer Martin [played by Daniel Weyman], whom I am there to mentor, but at the end, it seems to turn around.

So, the play keeps an audience on its toes?

It does. It’s up to the audience to decide whether the ending is really a reversal or if he’s lying again. On those terms, [the role] is something like Dar Adal, the person I am playing on Homeland. I’m not sure who that guy is, and I’m not sure who Rubin is either.

What are your—and Dar Adal’s—plans for the next season of Homeland?

We start shooting sometime this fall, but beyond that, I’m not sure. But wasn’t [season 6] the most wonderful finale?

How do you feel about the renewed vitality of your career due to Homeland?

You have no idea how far-reaching that show is! In this town, for instance, chock full of tourists, people will stop me on the street with all these different languages—Spanish, Italian, Yugoslavian—and go “Homeland!” [Laughs] It’s extraordinary: I sure am stunned by it.

What do you think the theater critic you played on Broadway a few seasons ago in Terrence McNally’s It’s Only a Play would make of The Mentor?

I have a line in this play about theater critics but I’m not going to tell you what it is; you’ll hear it for yourself. But doing Terrence’s play really was such fun; it felt like a great chance to get even.

Are you visiting while you’re in London with your Only a Play castmates Stockard Channing and Nathan Lane, both of whom are either currently acting, or about to act, on the London stage as well?

We’re actually supposed to get together after the show one night this week, but I don’t know about Nathan. I have a feeling after that show [Angels in America] that he’s going to go home and collapse.

What about Stockard, who is here rehearsing the play Apologia?

I’ll see her this week: she’s a superior actress and a superior woman, by the way. I can’t believe she didn’t get an award for that performance [in the McNally revival]. She’s a complete pro.

Did you have any words of advice for Nathan, given that you also played Roy Cohn in Angels in America?

I think for him as a gay man the ramifications [of the part] are quite different. For me, the biggest difficulty I had was that I hated Roy Cohn, and you cannot play a character you hate. With Nathan, he told me that the problem was playing a gay man who wasn’t permitted to come out in that period so has turned into that vicious person, and how you enter into that mindset. He’s confronting it from the other point of view.

What was it like appearing with two stage Salieris [Ian McKellen and Lucian Msamati] at the National Theater’s recent memorial here to Amadeus playwright Peter Shaffer?

That was just a stroke of great fortune. I happened to be rehearsing at the time, and so they invited me to show up, and there I was in this little room with all these living legends, like McKellen and Michael Gambon. For the first time in a long time, I wasn’t the oldest actor in the room: I was delighted!

At this point in your life [Abraham is 77], do you ever think of slowing down?

You know, I cannot imagine not working. I don’t understand the word “retirement.” I’m in very good health and have this deep love and rare passion for my work, so in other words, I’m very lucky.

Articles Trending Now

- Curtain Up on George Clooney in Good Night, and Good Luck on Broadway

- Odds & Ends: Dorian Gray Star Sarah Snook and Glengarry's Kieran Culkin Have a Succession Reunion on Broadway and More

- Molly Osborne Is Making Her Broadway Debut as the Desdemona to Denzel Washington's Othello—Maybe Someday She'll Believe It