Funnyman David Alan Grier Gets Serious in Race

David Alan Grier is widely known for being a funnyman on such TV shows as In Living Color and Comedy Central’s Chocolate News, but the Yale-trained actor is also a stage vet. He was nominated for a Tony Award for his debut in The First and has appeared on Broadway in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum and Dreamgirls. He also boasts a long list of film credits, both comedic and dramatic, not to mention a stint on Dancing with the Stars. Now the actor is part of the four-person cast of David Mamet’s provocatively titled Race, directed by the author. The amiable Grier—who is not one to mince words on stage or off—chatted with Broadway.com about playing a “truthsayer,” working with the Pulitzer-winning playwright and growing up during the upheaval of the 1960s.

Were you intimidated to work with David Mamet?

Yeah, because I read his book about actors when it was first released, and I was all appalled. [Actors] were like, “What?! How dare he!” I’m older now, and if I wrote a book about directors and playwrights, it would basically be the same thing: “Just write me good shit to say! Get out of my way! Give me more lines. Don’t tell me where to stand. Don’t have other people talking to me unless it makes me look better!” He is a great writer, so that makes it easy to come to work and easy to do the play. I know this character, I have a beat and a take on the character. The character is not me and that’s freeing. It’s not my political agenda; it’s not what I believe in. It’s the playwright’s world that I’m trying to bring and breathe life into.

There hasn’t been a big explanation about the plot of this play. The producers basically said that the title speaks for itself. Do you agree with that?

Yes, the first lines, which are spoken by my character, set everything out philosophically. It’s called Race, and we will get down and dirty right now. What’s deceptive is how it plays out. Race is involved in the basic plot, which Dave talked about in The New York Times: A white man is accused of a sexual impropriety with a woman of color. It’s good old-fashioned storytelling.

I think it’s fair to say that traditionally David Mamet does not have a very diverse audience. Do you think this play is changing that for him?

I hope so. Look at it this way: If I wrote a play called Jews, I’m sure there would be a lot of Jewish people who would see it—even if it were written by me, an African American. I’m serious. [People are] like, “Wow, what the fuck is this?” I know there’s that is the position of some African Americans because I had [that opinion] before I read the play. Like, “What can this white man tell me?” It’s called Race and it doesn’t let you down—just like if you had a play called Sex, but it’s about two people eating ice cream, you’d be severely disappointed. He has to mix it up, and he does. He talks about things that have rarely been discussed on stage with honesty and rawness. Also, I think it is interesting to do this play right after Barack Obama’s been elected. There’s that feeling of, “Oh, look how far we’ve come.”

The idea of being “post-racial.”

Right, and we’re not. Not yet. We’ve come a long way, but the conversation continues and for some of us, it’s more difficult than others. So there we go.

Despite its jokey cover and title, your book Barack Like Me: The Chocolate-Covered Truth is intelligently written. It reveals a lot about your upbringing.

Thank you. I didn’t necessarily know that it would come out more like a memoir and talking about the things I did. When I pitched the book, The Chocolate News [Grier’s short-lived show on Comedy Central] was on the air. Once we got canceled, I didn’t want to be stuck in that character’s voice; I wanted my own voice. So the tone of the book and the writing and what I was trying to say changed. It’s all about the world I grew up in, the family I grew up in and the beliefs I was taught. I had to tell that story, so people understood how I perceived and lived through the inauguration, the election period and all of that stuff with Barack Obama. That’s really the heart of the book.

You grew up in a politically conscious family—your father is a famous author [who wrote the seminal Black Rage], and now you’re in a play called Race.

Yes, it was all a plan [laughs].

People may walk into the theater knowing you as a comedian, but they might not know all of these other layers.

They have to learn, you know. It’s nothing I’ve hidden—it’s always been a part of me. My whole career, I’ve wanted to do a straight dramatic play on Broadway. Most people know me from In Living Color or Comedy Rules, but I’m a classically trained actor. I wish I could tell you it was some master plan, but it all kind of fell into place.

Let’s talk about your childhood a little bit. You really got to experience a lot of historical milestones as a young person.

My dad is retired now; he’s a psychiatrist. My mom was a school teacher. We grew up like real ‘60s kids. I was born in ’56, so I’m 53 years old. As a really young child, I got to experience a lot of important events—marching with Martin Luther King Jr. as a really young child. I remember seeing President Kennedy on the way to school as a really small child.

That’s a very moving section in your book.

It was so awesome as a little kid. For the book, I had to try and describe it so the reader could visualize Detroit with all these little box houses and the motorcade going down Woodward Avenue, which was a main strip. My mom was speeding down the side streets and every time we pass between houses, we would see a part of the motorcade. She finally got in front of it, put us on top of the roof and said, “When I say wave, wave!” We waited and the motorcade came, we saw the president. Then she was like, “All right, get in the car. You saw the President of the United States of America, now you can tell all of the kids at school.”

You got bragging rights.

Absolutely. For a long time, I thought I was too young to experience the ‘60s, and then I started thinking back and talking to my older brother and going, “Holy crap, do you remember when we went to the Black Panther headquarters?”

You really tried to join?

Oh, yeah! I was 15 years old. Of course, it was more about being sexy and cool than anything else. Any black dude who was yelling and screaming, that’s who I wanted to be. We went there, and they were like, “You young brothers, you’re too young. Come back when you’re 16.” We were like scared to death. We ran all the way home. We laughed about it later, but we actually went there.

What did your family think of your decision to become an actor?

My mom was really worried. She was like, “I want you to be a doctor, lawyer, Indian chief.” That’s what all the kids I grew up with did. Even when I got into Yale Drama School, she was really worried. She describes telling her friends—all these proper Negro ladies—“David was admitted into Yale,” and they’re like, “Oh, really! Med school, law school or dental school?” And she said, “Acting school,” and they all just went, “Oh, poor Aretas!” She got sympathy in her bridge club.

Well, now you’re playing a lawyer.

Yes! And she’s coming to the opening. She’s very excited. I even wear a power suit.

Is it freeing to play Henry Brown? He’s a man that seems to say what he thinks.

Absolutely. You need that. Within the structure of the play, I think you need that one truthsayer. Somebody has to be there to say, “No, that’s not what’s happening. I’m going to tell you what’s happening, I can’t stop you, but I’m going to tell you.” We’ve all met that person. You know, you say, “Oh, I met a great new girl. She may smoke a little crack, other than that, she’s great.” And that person is like, “Dude, good luck, but I don’t think it’s going to work out.” He tells it like it is. That guy.

What are people asking you about this play?

People want to know what it’s about, and I say very simply it’s about a rich white guy who’s been accused of a sexual impropriety with a woman of color. James [Spader] and I are partners in a law firm, Kerry [Washington] is a young lawyer we’ve hired. So we’re presented with this case. That’s basically what the play is about. Most people of color ask me if it’s down and dirty. Yes, absolutely! Does it deserve the title Race? Yes.

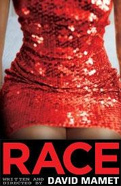

Well, this play certainly elicits a lot of discussion. Even the poster is provocative.

I love that. When we started previews, one woman was like, “Nobody wore the red dress!”

See David Alan Grier in Race at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre.