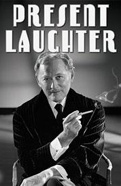

Present Laughter's Harriet Harris Shares the Secret of Great Comic Acting

About the author:

Tony Award winner Harriet Harris knows how to land a laugh. The sharp-witted actress has been busting guts on and off-Broadway for years in shows like Jeffrey, The Man Who Came to Dinner, Old Acquaintance, Cry-Baby and, of course, Thoroughly Modern Millie (which earned her that Tony trophy), making it look easy all the while. Harris is at it again, zinging one-liners and stylishly slamming doors as wry secretary Monica Reed in Roundabout Theatre Company’s Broadway revival of Noel Coward’s Present Laughter, starring Victor Garber as her boss, Garry Essendine. We asked this expert of laugh engineering to school us in the fine art of Coward comedy—and she didn’t disappoint.

![]()

The good people at Broadway.com have invited me to get up on my high horse and talk about “acting in Noel Coward.” This is a topic about which I know precious little—and, as I have an aversion to horses of any height, I am left to ponder why I said “yes” when my character, Monica Reed, would have dictated a “polite refusal.”

My ignorance is both deep and wide. My preferences, however, are shallow and narrow as a gerbil’s grave. I don’t absolutely know how to act Noel Coward. But I like to think he has left us clues on every page.

I like to see a page full of punctuation—it makes me as happy as fresh snow on Christmas or fireworks on the Fourth of July. Out of laziness and an inability to accessorize, I skipped a lot of school as a child and can’t punctuate my way out of a paper bag, but I am full of admiration for those who can. Coward was an actor, author, director, painter and a musician (ay-yi-yi, I feel so small), so certainly he meant us to observe the melody and rhythm of his lines. Sometimes they leap and gallop, sometimes they canter or trot. Yes, the rhythm lies is in the words. But it lives in the punctuation.

To paraphrase: “Sometimes—there’s an exclamation point—so quickly!” In our play, they dot the page like crosses on Southern California hillsides. It's the most beautiful of all the diacritical markings. It looks wonderful, tall and taunting: “Hey, batter, batter, batter!” What it sounds like may be open to interpretation, but it doesn’t sound like a period. I don’t think he ran out of those; if he had, I’m sure he was clever enough to get more.

If Coward gives you a bat, for heaven’s sake use it. These lovely signposts are like a Michelin guide for those on a quest for comedy. If one is tempted to ignore the guide and go off road for a cheap thrill, one may well get lost or, at the very least, disturb the breadcrumbs for fellow travelers. For all the beauties of Soledad, I would rather travel from Monterey to San Luis Obispo on Highway 1. A better time will be had by most, and some passengers—or audience members—will remember it for the rest of their lives. You might opt for the 101 but you will miss Carmel, Point Lobos, lunch at Nepenthe, Big Sur and San Simeon. (If however you have a craving for Cheetos or business at the prison that cannot be deferred, by all means beat a path to Soledad.) Anyway, pay attention to Coward’s cartography and a wonderful opportunity for comedy, not just laughs, presents itself.

Another thing I dislike, and I’m guessing Coward did too, is a big fat pause. Please don’t take one unless it is your last best hope. Yes, it can be short-term funny, but it is long term horrible—it’s enervating and requires heavy lifting for the following 73 seconds. The unnecessary pause is comedy's filibuster. Coward tells us where to pause. It’s on his map. “How will we know?” He writes it in. It looks something like this:

[Pause]

But note his pause is more like a scenic lookout than a place to hook up your camper or refuel your gas-guzzler. He is always moving us forward to the next opportunity.

The last thing I have noticed and learned to like is the incredible length of some of Coward’s lines. Some are so long they must be a song for mermaids or those oboists that can do that circular breathing thing. Mortals have their work cut out for them. (Why, I would like to know, if people were shorter in 1939, were lungs so much bigger?) Coward and his pals must have had been breath incarnate. But a deep breath is good for the soul, so embrace it. Try to manage the full arc of the line. We know we are supposed to do this in Shakespeare. With all due respect to Shakespeare, he is not the only writer who stopped drinking long enough to get the line right.

For the most part we do pretty well over at Present Laughter. The challenges are great, the climb is steep, there are no oxygen tanks waiting in the wings—but everyone is game and we have had all our shots. It’s a lovely cast full of seriously silly people. The only thing better than sitting around together before the show is getting to do this wonderful play, where for a time we are brighter, quicker, more fleet and deft, and at least one of us [ahem, Brooks Ashmanskas] is able to leap a pouffe in a single bound.