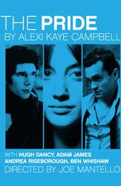

Hugh Dancy on His Proud Stage Return in MCC's Provocative The Pride

Hugh Dancy’s characters all have one thing in common: They’re as handsome as Hugh Dancy. Outside of that, there are few similarities among the roles that comprise the Brit's impressive resume. Since breaking out in 2001’s Black Hawk Down, the 34-year-old has jumped nimbly from mainstream to indie film projects, playing everything from a dashing fairytale prince in Ella Enchanted to an antihero with Asperger’s Syndrome in Adam to an unrequited lover in the starry Evening (where he met his bride, Claire Danes). Dancy punctuated this diverse bio with a critically acclaimed Broadway debut in 2007’s Tony-winning revival of the World War I drama Journey’s End. For his current return to the stage in MCC’s provocative love-triangle drama The Pride, Dancy has again shed his skin, this time taking on two difficult characters, both named of Philip (one a closeted 1950s husband and the other jilted, modern-day boyfriend in a dysfunctional gay relationship). In a recent conversation with Broadway.com, Dancy spoke about his pride in The Pride, what frustrates him about his complex new role and how he keeps that resume interesting.

You’ve said you agreed to appear off-Broadway because The Pride was such a good script. What made it stand out?

The structure is brilliant. On the page, not yet taking into account how well it works on stage, you immediately notice this is bold and provocative writing. But for me, the most remarkable thing was the dialogue. In every scene we find both an exchange of ideas and the characters fighting for their lives, but the dialogue remains natural, convincing and, at the same time, incredibly eloquent.

The Pride is a fairly dark show. Was that part of the appeal for you?

I think there are elements of darkness in the play, but I personally don’t find it to be a “dark” show. There are certainly unsettling moments, but there's a tempered optimism too. I think it leaves you with hope—it just does it without boldly stating, “Hey, everything’s fine and aren’t we all so great?” What appealed to me was that balance between dark and light.

“Unsettling” is the right word. As a fellow actor actor, has it been hard for your wife [Claire Danes] to watch you go to such uncomfortable places nightly?

As far as my wife goes, I think she’s pretty brave to ever watch me on stage. If you’ll forgive me though, I do think there’s a sort of unspoken question in there, [one that] lies in this show dealing with gay themes. Without giving too much away, there is one scene in the first act that is really unsettling, but to me whether it’s homosexual or not is irrelevant. What I'll say is: I’ve been asked a lot about playing a “gay” character, but not once has someone asked how I feel about playing the sort of character that might brutalize another character! I find that frustrating and amusing in equal measure.

How draining is it for you personally to go to the places emotionally that that scene, and this play, requires?

The nature of this show is that the better it goes, the more draining it is. I think all the characters are pushed to fairly extreme places that, if you commit, require that. So if you get to the end of the evening and don’t have that drained feeling, it’s actually a bit unsatisfying.

How do you detox once the curtain comes down?

If anything, I think I tend to “tox” at the end of the night! [Laughs.] It’s a mixed feeling. That tiredness comes with the feeling you’ve hopefully done your job right. When the scenes that are the hardest or the bleakest work well, you feel you’re really doing justice to the play, which is what we’re all aspiring to.

What has been the biggest challenge for you in this role?

The fact that the play jumps between these two time periods, 1958 and 2008, adds a level of challenge. And the stakes are very high for everyone on stage all the time. To get to that place every night without exhausting the audience can be difficult.

Watching this play, it’s easy to forget you’re the same guy who’s played princes [in Ella Enchanted] and sympathetic indie-boys [in Adam]. How do you account for such a diverse resume?

I don’t know. It’s always funny, trying to analyze your choices after the fact. You can never predict what’s going to speak to you when you pick it up. I can say that regardless of style, theme, whatever, the dialogue is key. Really good material is rare. I guess most actors are kind of plying the ground between what is mainstream and what appeals to them on a personal level. But I think it comes down to what comes through your personal door. I’m not really concerned with making a piece of super-broad, lowest common denominator entertainment, but if I find a romantic comedy where all the people involved are the best at what they do? Sign me up.

Your career has been mostly in film, but you started in theater. Did you want to do one over the other growing up?

Doing theater in school is that’s what hooked me [on acting]. Once I started working professionally, as is not uncommon, I just found myself working mostly in TV and film. I sort of strangely had to do a curve to get back to what it was that I first enjoyed, which was be on stage. And I’m really, really glad that I did.

Do you remember your first time onstage?

I was about 10, in the chorus of Bugsy Malone, as a down and out boxer. I also had a cameo as a barber. The first bigger role I had was in Waiting for Godot. I played the boy, though! It’s not one of the great roles of the canon, but the play at least... [laughs]!

How significant was your Broadway debut [in Journey’s End] to you?

It was incredible. Understandably, people who are rooted in Broadway sort of feel that Broadway is unique, while people who are rooted in the West End think of the West End as being unique, but of course they share more than they differ. That play specifically was incredible for everyone involved, and not just the work. Personally speaking, it was a stand-alone experience. I’m having a wonderful time with The Pride as well! But Journey’s End created lasting friendships and was an all-round good time.

You got excellent reviews in a challenging role in Journey’s End, but were not nominated for a Tony alongside co-stars Boyd Gaines and Stark Sands. Did you feel robbed?

I really didn’t! That show truly felt like an ensemble, and I felt I was resting on everybody’s else’s shoulders. I know they’d say the same about me. So I mean it when I say all of us taking the stage together to accept the Tony for Best Revival felt like the most appropriate thing that could have happened.

You’ve spoken about how plays like Journey's End and Black Hawk Down required a great deal of research. Did The Pride require similar legwork? And I don’t mean going to gay clubs.

Because the show’s partially set in 1958 in Britain, the culture of that time and place and how they viewed gay men then is important to understand. The character I play [in that portion of the show] certainly believes he is “sick,” and knowing that that was not uncommon for men of his era is sort of key. Alexi, our playwright, had done a great deal of period research and was an invaluable resource, but it was also about reading a lot.

What did you read?

For example, in 1957 the Wolfenden Report came out, which was the British government’s investigation into female prostitution and male homosexuality. Out of that report came various recommendations that weren’t applied until years later, including the legalization of homosexuality. Reading about that report tells you a lot about the assumptions of the time, as well as pressures on the government from the church and media to handle things a certain way.

There’s been a lot of focus The Pride being a “gay” show, but that’s an easy, almost trite, label.

It’s true, and I think this play is more about identity. Assuming the right to define your own identity is a difficult responsibility for anybody—I’m not talking about sexuality so much as who you are in life. It can be very easy to let people’s perceptions define you. So, more than sexuality, it is about the possibility that you can address who you are and then do something about it. That’s a huge idea! And the flip side of that, and what the play also rather brilliantly examines, are people who are terrified by that idea, for whom the idea of change is unbearable.

Which is an even more timely a theme than sexuality, in a lot of ways.

Exactly. There will always be people, in 1958 or 2008 or whenever, who will be terrified by change. I mean, all of us have been there at one point or another. And that’s probably the third component of this show: how a set of [out-dated] cultural assumptions or rules can still be in play 50 years later, just [manifested] in totally different ways. That’s what I meant when I said the structure of this play is brilliant, because it lays that point bare for everyone to see.

See Hugh Dancy in The Pride at the Lucille Lortel Theatre.

Related Shows

Star Files

Articles Trending Now

- Death Becomes Her, Maybe Happy Ending, Oh, Mary! and More Earn Nominations for the 2025 Broadway.com Audience Choice Awards

- Ragtime, Starring Caissie Levy, Joshua Henry and Brandon Uranowitz, Is Coming to Broadway

- Carrie St. Louis, Katie Rose Clarke and Quinn Titcomb to Star as Dolly Parton in World Premiere of Dolly: An Original Musical