Michael Friedman on Turning History Into Hysterical Antics in Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson

About the author:

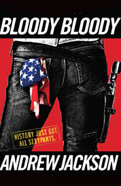

If anyone can take an obscure subject, wrap it in a catchy melody and make it sing—literally—it’s Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson’s Michael Friedman. The composer, lyricist and consummate satirist has taken on such varied (and potentially deadly) topics in recent years as fanatic Christianity in Saved (a Broadway.com Audience Award winner), social politics in Paris Commune and the daily tragedies of urban living in Gone Missing, working each tricky subject into musical scores that are both hummable and laugh-out-loud funny. (If you don’t believe us, keep an ear out for Andrew Jackson’s “Populism, Yeah Yeah,” one of the most radio-friendly hits ever penned about political ideology.) Friedman is at it again in his newest musical, an outrageous emo-rock satire playing through May 9 at the Public Theater. Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson uses pop themes and potty humor to draw poignant parallels between the rise of the nation's seventh President and the state of America today. Here, Friedman discusses why he and Alex Timbers have enjoyed spinning Jackson’s biography into a musical comedy, and why—for him—fact will always be more entertaining than fiction.![]()

The catchiest song in Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson was actually written in 1824, to commemorate a battle fought in 1814. For our curtain call, we sing a pseudo-punk cover of “The Hunters of Kentucky,” which describes (in mostly hagiographic terms) Jackson’s great victory in the Battle of New Orleans, which was in no small part responsible for Jackson’s presidential victory in 1828. Inaccurate in most details and full of questionable lines (“For ev’ry man was half a horse/And half an alligator” or “Just send for us Kentucky boys/And we’ll protect your ladies”—for the record, Jackson was from Tennessee, not Kentucky), it was a great big hit. It was also America’s first campaign theme song.

People coming to see Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson have asked why we use an emo-inspired score to tell the story of Jackson’s role in American history, and while the reasons are varied, the simplest answer is that [librettist and director] Alex Timbers and I have enjoyed tracing the parallels between Jackson and emo rock—their common qualities of masculinity, sensitivity, cockiness, vulnerability and rock stardom—and how that reflects some of the most infectious and pernicious qualities in American culture.

Part of the reason that Alex and I were interested in telling Jackson’s story was excitement of the mash-up of the past and the present. [In this show], Jackson’s first campaign speech presents 19th century issues in a very 21st century way. The music mixes 19th century tropes with electric guitars and really big speakers. Cowboys and politicians in tight jeans and 19th century coats sing rock songs that mix up de Tocqueville and Foucault, James Madison and Susan Sontag. An old-school song and dance describing the corrupt bargain of 1824 segues into a punk-rock campaign rally.

As we teased out these parallels, we started to realize that almost every recent President—Carter, Reagan, Clinton, W, Obama—not to mention Palin and the Tea Party—has reflected a facet of Jackson’s canny blend of populism and personal charisma; his distrust of status quo politics masking a sometimes disquieting ambition for America. “It’s Morning in America,” “Change,” “Don’t Stop Believing,” and George W. Bush’s rewriting of his aristocratic past all sound like Andrew Jackson.

The transformationof "The Hunters of Kentucky" from inaccurate-but-catchy pop tune to political anthem shows the weird and hard-to-exactly-pin-down relationship between politics and pop culture. I think that, unintentionally and certainly unsystematically, I’ve been exploring what that relationship can look like in a lot of recent shows. 2008’s Paris Commune traces the downfall of a popular uprising using popular songs, written by its leaders, that document the events almost journalistically, and some of which later took on new and unexpected lives in popular culture; 2009’s This Beautiful City uses the cheesy, wildly seductive power of Christian pop to help [audiences] understand the power of the evangelical church in American life; and in Fortress of Solitude, a changing neighborhood in Brooklyn is reflected in the changing pop music influencing the lives of the characters.

In the latter two of these shows, as well as in Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, my riffs on popular styles are sometimes willfully ignorant, sometimes inaccurate, and bound to upset purists. That said, by the curtain call, I hope the collision of a historically questionable 19th century campaign song and a few stolen punk gestures captures a small part of the American character that can be confusing, alluring, infuriating, and sometimes just too fun for its own good.

Related Shows

Articles Trending Now

- Death Becomes Her, Maybe Happy Ending, Oh, Mary! and More Earn Nominations for the 2025 Broadway.com Audience Choice Awards

- Maybe Happy Ending Will Be Hitting the Road on a National Tour, Launching Fall 2026

- Ali Louis Bourzgui Reflects on Joining Hadestown, His Upcoming Album and Processing the Experience of Tommy