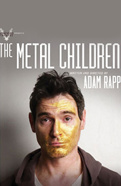

Adam Rapp Transforms His Brush with Censorship Into a New Play, The Metal Children

About the author:

The hot-button topic of book-banning has been transformed into an absorbing new drama, The Metal Children, now playing at off-Broadway’s Vineyard Theatre in a production starring Tony winner Billy Crudup. Playwright/director Adam Rapp was inspired by a personal brush with censorship: Five years ago, a school in Reading, PA, locked away (literally!) copies of The Buffalo Tree, one of seven young adult novels Rapp has written. Mulling the experience of defending his work at a town meeting, Rapp (prolific author of plays such as Red Light Winter, Essential Self-Defense, Nocturne, Kindness and American Sligo) decided to explore all sides of the issue, with Crudup giving a masterful performance his onstage alter ego. The author recently took the time to explain how the controversy over The Buffalo Tree morphed into The Metal Children.

![]()

In the spring of 2005, I received a call from Bruce Weber of The New York Times telling me he was about to travel to Reading, Pennsylvania, where my young adult novel The Buffalo Tree had caused a bit of a stir. The novel, published by Front Street Books in 1997, was a part of the English curriculum at Muhlenberg High School, and a young woman, purportedly “puppeteered” by a local Christian group, quoted passages from the novel containing sexual content and foul language in front of the local school board. The book was immediately pulled off of shelves, wrested from student hands, and all copies were banished to a large vault.

Mr. Weber told me there was going to be a town meeting to discuss the improper procedure implemented in “banning” the book. He said that the major players on both sides would be present, and he asked me if I was going to attend. This was certainly a shock to me. I couldn’t go. I was in Chicago and about to start tech rehearsals for the world premiere of my play Red Light Winter at Steppenwolf. We’d only had three and a half weeks of rehearsal, and I was directing. This isn’t much time to get things up to speed, and I told Mr. Weber as much. He called me from the meeting and put one of the students on the phone with me. She had apparently stood up in front of her community and offered her copy, which she owned, to the library so that other kids could continue reading the book. She was extremely excited to talk to me, and I was moved to tears.

Incidentally, Red Light Winter opened without a glitch and all was good in Chicago. Bruce Weber went on to publish an article about The Buffalo Tree and the controversy at Muhlenberg High School in the Times. The book remained off the reading list, which saddened me. I was grateful that he gave the matter so much attention. I cut the article out of the newspaper and put it all behind me.

A year later, that community in Pennsylvania called for another meeting to discuss the book, how the decision to keep it off the reading list affected students and teachers, and how the whole experience was possibly changing the way reading materials are selected for English class. I was contacted by the courageous, progressive teacher who led the charge in favor of The Buffalo Tree, and he invited me to be a part of the conversation. I agreed to come and when I arrived in Reading, I was met with all the major players on both sides of the issue. There was a dinner at the home of the provost of the local college. It was all very civil. The food was good. I was nervous.

The actual meeting was held in a Lutheran Church. There was a large banquet table set up on the altar, with pitchers of water and Styrofoam cups. Organ music played while people filed in. I was placed in the center of the table. On either side of me were people who loved and hated the book. The plan was to hear the various points of views of the people seated at the table, then the public would have an opportunity to ask questions and share their opinions.

When I was asked to speak, I did so from a pulpit. No one else had to do that, but it was offered to me and I took it. I had nothing prepared. The whole thing felt surreal. I heard myself saying things about never wanting to hurt anyone and not having any real intentions for the book beyond telling the story of a young boy who was trying to survive his brief but brutal stay in a reform school.

I felt like I was speaking passionately, but I also felt far away from my own material. I’d written it in 1995, after all, 11 years earlier. I remembered character names and most of the significant actions. I told the audience I really was interested in writing about survival and mercy and loyalty; that it was a violent world I was dealing with, but none more violent than the stuff we see in the streets, on TV, on the Internet. I told them how hard it was to write the book; that it was personal, drawn from some of my own experiences when I was sent to reform school for half of the fifth grade. But with many of the specifics in the novel, there was a kind of amnesia at play, and it was this memory loss that haunted me as I took the train back to New York.

I started to think about how a piece of art, specifically a work of literature, can have its own life. The book itself— the artifact—can gain power completely independent of its creator. The Buffalo Tree received some nice reviews when it was published, and it went on to be named a 1997 School Library Journal Best Book for Young Adults, but it was by no means a bestseller. It has managed to stay in print, but my royalty checks—the few I’ve seen for it—can barely pay my rent. I moved on from that novel and wrote more. And I’ve written plays and a few films and television scripts. Eleven years after its first printing, I was stunned that my book was causing such a mess. And I was sad that it had drifted from my memory.

Many other things happened that evening in Reading. One brave student approached a lectern, which was placed in the enter aisle of the church, and confronted the head of the school board, asking him why he felt he could make decisions about what kids were capable of processing with regard to sex and violence when he’d never even spoken to one single student and had little or no presence in the high school. About a hundred students stood up and cheered, and the hair on the back of my neck stood up. A standing ovation at the curtain call doesn’t even come close to what I felt in that moment.

I wanted to write a play about a book, which is a strange thing to do because books aren’t people and they don’t do anything. As objects go, they are about as passive as it gets. As I started the play I realized I was actually writing about people. I was writing about a lost writer and impassioned teenagers and a loving aunt and a precocious 16-year-old girl who grew up in a motel.

The book within the play (entitled The Metal Children) is about a rash of teen pregnancies and what it does to a small town in the heartland.

In some ways, the play The Metal Children is a fantasy of what I was expecting in Reading. It is part nightmare, part old-fashioned wish, and my attempt to meditate on both sides of an issue that means a lot to me: kids reading books. I’ve always believed that kids are much wiser than we think they are, and to deprive them of complex expressions of art because of violence or sexual content is to condescend to them.

In writing this play, I’ve also found that the works we move on from, whether they are novels, plays or poems, come back to haunt us in ways that are hard to articulate. They are like these wandering, well, children, who never grow up, who periodically come in out of the cold and make us look in their enormous, wondering eyes. They leave us alone for a while, and we love them from a strange distance.

In preparation for the workshop production of The Metal Children, I re-read The Buffalo Tree. When I finished, I honestly couldn’t decide whether it was appropriate for all kids who are 14 and up, as it says on the back of the book. I don’t have kids. I think in some ways, I have never grown up and therefore I consider myself good source material, but the closest I have come to parenting has been raising my three-year-old dog, Cesar, who happens not to read and, in fact, speaks very little English.

But if I had a little girl or a boy, perhaps I would find the content in The Buffalo Tree salacious and unnecessarily violent. Therefore it was important to me to discuss both sides of this issue, to not easily dismiss those who are against the novel (The Metal Children) within the play. And as the play The Metal Children has developed, I have done my best to honor this.