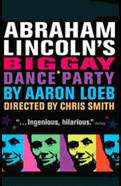

Playwright Aaron Loeb on Sending the Invite to Abraham Lincoln's Big Gay Dance Party

About the author:

The title may have been the first thing that caught theatergoers' eyes, but it was the content and execution that made Aaron Loeb’s uproarious, topical comedy Abraham Lincoln’s Big Gay Dance Party one of the stand-out hits of the 2009 NY International Fringe Festival. Naturally, when we heard the show was being picked up for a full off-Broadway run, beginning July 27 at the Acorn Theater at Theater Row, we had just one question: “So, um, gay Abraham Lincoln—yeah, what’s up with that?” Scribe Loeb (First Person Shooter) was nice enough to answer in full detail, taking us back to the source of his love for Lincoln, how he came across the radical idea that sparked the play and the fun of being behind a production that “basks in silliness, song and dance.”

![]()

I grew up in Central Illinois in a college town (Champaign-Urbana). What people from other states will never, ever understand is the depth of our love for Abraham Lincoln. I don't say that sarcastically. I don't know if it's like this for kids from Chicago—or even for kids from Central Illinois today—but back there, back then, Abraham Lincoln was the legend around every corner. There was the Cattle Bank (Lincoln used to have an account there!); the old courthouse (he argued cases there!); some old building that used to be a hotel (he slept there!). And there was the tomb and the shop.

Every year in grade school we would get on a bus and drive the two hours to Springfield to see Lincoln's tomb and learn the story of Illinois' favorite son (who was actually from Kentucky and Indiana, but we didn't question Illinois' status as the Land of Lincoln): He saved the whole country! He kicked the collective asses of racist tyrants! He was a bearded Superman! (We didn't question any of these narratives either.)

From there, we would get back on the bus and go to "Lincoln's New Salem" in Menard County, Illinois. It's a re-enactment community built to look like the town where Lincoln ran a shop. My recollections of seeing "Lincoln's shop" every year ought to be narrated by Sarah Vowell—they're memories of Americana, patriotism, heritage, vaguely musty smells and acute boredom. The point is, Abraham Lincoln was, for me, what I guess Reggie Jackson was for New York kids of the same era.

In 1999, Larry Kramer famously gave a speech in which he proclaimed he had proof Abraham Lincoln was a homosexual. This had long been discussed by those "in the know," but somehow Kramer managed to launch the question into the mainstream. C.A. Tripp's posthumously published The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln sealed the deal, forcing historians as famous as Doris Kearns Goodwin to answer the question: "Was Lincoln gay?" (Google it! She doesn't think so.)

For most people, this is a question, perhaps, of little relevance. [But] for me, it's like asking "Is Superman gay? Is America gay?" Given how much of our modern discourse is about identity, freedom to identify (or not identify) openly with this group or that and freedom to teach and discuss ideas about identity to our children...well, I find the question of Lincoln's sexuality to be both deeply personal and incredibly relevant to our present national divisions.

I knew this was a topic that could easily be approached in a deeply ponderous fashion—and man, did that sound like a drag. So I sought to create a piece that had a deep seriousness of purpose, but happily basks in silliness, song and dance. Thus, Abraham Lincoln's Big, Gay Dance Party was born.

I was inspired to do three things: First, I wanted the play to capture the Illinois of my youth, where Lincoln lurked in every shadow and sign; second, I wanted to use the question of his sexuality to explore the profound rifts in our country over "the politics of gay"; third, I wanted to create a dramatic device that captured the completely disparate responses people have to gay Abe. I'll explain.

As I told people, "I'm writing a play about whether Lincoln was gay," reaction would vary enormously. Some people would laugh and then get kind of pissed off. Some would light up. Some were hostilely perplexed. Others would merely shrug (though very few). It became clear to me that an individual's context made this much more volatile than the average historical question. For instance, if I had said "I'm writing a play about whether the Louisiana Purchase was a rip-off," I imagine reactions would be less intense and varied.

This led me to the idea of changing the audience's context nightly. I wanted them to have a different way of understanding the characters than other audiences. To accomplish this, I wrote the play so that its three acts could be performed in any order. And the order changes the audience's basic description of the story and its characters. In one, it's a mystery. In another, a tale of redemption. In yet another, a cautionary tale. In this way, I hoped that audiences' answers to questions about the characters would change as widely as people's reactions to the question of Lincoln's sexuality.

The play had its world premiere in San Francisco at SF Playhouse in December 2008. It received quite a few local accolades and, from there, went to the New York International Fringe, where it won Outstanding Production. Now it's opening off-Broadway at the Acorn in Theater Row. It feels like a dream. I know everyone involved in the production is thrilled to unveil it for a broader New York audience. I certainly hope you will come join the party.