From Intelligent Homosexual's Guide to American Idiot and Back, Michael Esper Reflects on an Exhilarating Year

About the author:

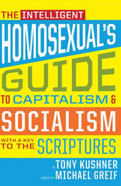

Michael Esper’s last name is synonymous with excellence in acting: His parents, William and Suzanne, teach at the famed William Esper Studio, and his dad heads the theater program at Rutgers University, where Michael studied. But there’s no doubt that the younger Esper has earned acclaim on his own merits, amassing an impressive list of off-Broadway credits and winning the prestigious Clarence Derwent Award for his work in A.R. Gurney’s Crazy Mary. All that prep has helped Esper make the most of a pair of roles he has spent the past two years juggling: Will, the disaffected stoner and reluctant father in the Broadway musical American Idiot; and Eli, a charismatic hustler involved with a much older lover (Stephen Spinella) in Tony Kushner’s The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism With a Key to the Scriptures, now playing at the Public Theater. Esper recently took time to write about his experience in this exciting pair of theatrical projects.

![]()

Over the past two years I’ve gone back and forth from American Idiot to Tony Kushner’s Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide and back to Idiot and then back again to Kushner. Both projects were and are huge experiences in their own ways, and it’s been kind of insane. So much experience is packed into that time that I almost can’t believe it was just two shows. Feels like it should be more. But then, both Idiot and Intelligent Homosexual are huge pieces with huge experiences built into them. They’re both dizzying, exhilarating rides that pulled me all over the human spectrum. If that’s even a thing. No, it is. The range of human experience is what that is. And both pieces demand that huge swaths of it be explored. Huge human areas.

As different as they are, I get struck by where they’re closest. Love and alienation, particularly self-alienation, where politics meets personhood, safety and risk, fear and selfishness, the questioning of basic assumptions about ourselves and about our world and what we take for granted, responsibility to oneself and ownership of one’s life versus responsibility to society and to others, the nature of love and self-destruction, and, of course, the problem (is it?) of being more than a little in love with death, particularly suicide. And though that sentence is criminally long, I think you can find most if not all of that stuff in both plays. They both say (albeit very differently) look around...now, given what you see, how should we live our lives? How should we organize ourselves? For what? In the name of what? In opposition to what? Should we do that at all? Should I even be here?

So, you know, that’s a lot.

It’s an enormous thrill to be a part of something that’s engaged with the world on that level. And, it goes without saying, to be engaged with artists like that, who work on the level the artists I’ve been lucky enough to work on these pieces with do. That alone. We could have all gotten together and made cookies and I’d have been challenged and inspired. I mean, it’s better we didn’t, but you know what I mean. I think they’re all so amazing is what I’m saying.

Both pieces started up for me around the same time. Idiot was a little sooner. I was doing one of the early workshops when I first worked for Kushner on a reading. Those Idiot workshops were incredible. Physically rigorous and vocally demanding and so exciting. I had absolutely no idea what I was doing. I’d never been in a musical on that scale before, and although I felt connected to the world of the show, there was a real “please don’t let me suck” thing happening. And a real sense of collaboration and community. That we were being challenged as a community, and creating as one. That’s mostly true, I think. And all of it was infused with this wild feeling of experimentation. There was a palpable collective excitement about what we were doing, what we were trying, trying with everything we had available to us. We all wanted the best of ourselves to go into it, to meet that music, to rise to it and fill it out with all of who we were.

I saw Angels in America in high school, and it changed me. I didn’t know theater could be like that, so huge and so small at the same time, so epic and so particular, the personal never drowned out by the bigger questions but rather immediately felt as at the center of them. It felt so fearless. I didn’t know actors could do that. I didn’t know how the actors did that. Made that extraordinary thing and then lived it through so deeply time and again. I should seriously ask him. Spinella. I’d be embarrassed though. “Stephen. HOW do you do that?” Like, that just sounds bad.

So when I auditioned for the new Kushner play, and when we started working on it initially, we didn’t have written material. It’s not that there wasn’t a play, because there was, we just didn’t have written material. Instead of beginning with the words, we began with conversations. Tony spoke to us about the world of the play, what he was thinking about around it, the relationships in it, and who we were. He spoke to me about Eli (the character I play), what he thought about him, what he doubted about him, where he lived, what he did, things he was interested in, his world. It was an incredible way to start. Purely imaginatively. Pure fantasy. No way to get mired in “I wonder what the best way to say this line is?” Just spending time in the imaginative world of who this person is. Amazing.

And then, when were in Minneapolis working on it, pages would come in throughout the day. I’d be called in to rehearsal, and Tony would come down and hand us pages still hot from the printer, and I’d read them through, these unbelievable scenes, for Michael Greif and Tony, with Stephen Spinella mostly, who awed me as a kid in the audience of Angels, and now awes me as an adult actor on the stage of the Public Theater. So. That’s a truly remarkable thing for me.

The pieces are so different, of course, singing and not, suburban punk and not, dancing/couching and not, and on and on. I have totally different hair now and stuff. The worlds are very different. The modes of communication are very different, the styles are very different, and so therefore are many of the demands and rewards. It’s been dizzying at times, readjusting to one or the other. Confusing at times, frustrating at times, terrifying at times. They both have a kind of feverish intensity that can easily overwhelm as it exhilarates. They both say, “If you really believe in me, and understand me, and love me, you’ll do x.” And x is a very large number. So that’s hard.

But it should be hard that way, right? I’m so lucky for that kind of difficulty. That’s what we ask for when we say we want to be actors, what we hope for and maybe never get. To be so tested and extended? To be fighting in the center of something we believe in? To be working not just on something but for something? That’s it. That’s what I’ve gotten to experience the past two years. I have this in me? And this? And this? And though navigating the differences in the shows was tricky sometimes, hard to let go of one, lost in another, and then back the other way around, that feeling was a shared constant between the two of them. Of being for something. Of being bettered. And thank God. Although, perhaps as a result of all the feverishness, I sometimes still have no idea, like, where I am. So also maybe, thank god for google maps. And friends and family, and therapy and cookies. And OK, I’m done.

Related Shows

Star Files

Articles Trending Now

- Nominations Are Open! Choose Your Favorites for the 2025 Broadway.com Audience Choice Awards

- Tickets Now on Sale to Broadway Revival of Waiting for Godot, Starring Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter

- 2025 Drama League Nominations Announced; Idina Menzel, Helen J Shen, Nicole Scherzinger, Lea Salonga and More Up for Awards