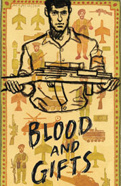

Tony-Winning Blood and Gifts Star Jefferson Mays on the Challenge of Bringing History to Life On Stage

About the author:

Since winning the 2004 Best Actor Tony Award for his astonishing performance as a cross-dressing antiquarian who outsmarted the Nazis and East German secret police, Jefferson Mays has appeared in two additional plays that delve into real-life events: the Tony-winning 2007 revival of R.C. Sherriff’s World War I battlefield saga Journey’s End, and now J.T. Rogers’ Blood and Gifts at Lincoln Center Theater. In this story of the secret spy war behind the Soviet-Afghan war of the 1980s, Mays plays British secret service agent Simon Craig, one of the many operatives who get involved in the conflict over the course of a decade. Broadway.com asked this distinctive actor to reflect on the challenges of bringing history to life onstage and preview this ensemble drama, which opens on November 21 at the Mitzi Newhouse Theater.

![]()

I’ve always loved the theater because it’s such an unabashed liar —sets are painted canvas, “toupee tape” shimmers behind a hastily applied moustache and, through two hours’ traffic, players and audience agree to suspend their disbelief and together ascend the brightest heaven of mutual invention. It’s always struck me as miraculous that through theater’s sheer flimsiness and childlike sense of make-believe, the greatest truths can be told.

As we’ve been exploring and inhabiting the bloody, chaotic, upside-down world of 1980s Afghanistan in J.T. Rogers’ Blood and Gifts, my very idea of acting has been stood on its head.

I’m no stranger to plays that are based on “the Truth”: real events and real people. I Am My Own Wife chronicled the life of German transvestite Charlotte von Mahlsdorf’s survival of the Nazis and Communists living openly as a cross-dresser; Journey’s End was thinly veiled reportage of R. C. Sherriff’s own experiences as a young officer with the East Surrey Regiment in the trenches of World War I.

Here, too, our Blood and Gifts company (probably the most diverse and thrilling assemblage of passionate hearts and curious minds with whom I’ve ever worked) has been immersing itself in the head-spinning history, customs and politics of a troubled region that has been so aptly named “The Graveyard of Empires.”

Real-life CIA officers, journalists and UN negotiators who have come in to speak to us and read drafts of the script have told us how truly the play’s characters and events ring, and we feel keenly responsible to conveying that truth.

While preparing I Am My Own Wife, I was acutely aware that the real Charlotte might end up seeing her incarnation. (She passed away in 2002, just before I was scheduled to meet her in Sweden; I’d like to think the prospect of the meeting didn’t play a part in her sudden death.) And there was little danger that a former inhabitant of R.C Sherriff’s trench would come to the theater and give notes. But at the Mitzi Newhouse, we know that we will soon play to audiences that, along with our citizen subscribers, will include diplomats, soldiers, Afghan refugees and journalists, all of whom have an intimate knowledge of, and investment in, our subject.

Generally, we actors try to find elements of ourselves to bring to our characters. It is only natural, and indeed valid, to start from the self and ask, “How am I like my character? How is he like me?” But the truly interesting, surprising and often revelatory work begins when an actor extends beyond himself, feeling his way in the dark toward the unfamiliar and unknowable and giving shape to the mystery of character in all its contradictions and ambiguities.

It has been a joy throughout rehearsals to see my castmates so extending themselves. Bernie White, who plays the Afghan warlord Abdullah Khan, has worn the traditional Afghan shalwar kameez and pakol hat from the first day of rehearsal and goes to sleep every night to the beautiful susurration of Voice of America Pashto, letting the cadences of his adoptive language seep in. Gabriel Ruiz, who is of Puerto Rican ancestry, has been exploring the Pakistani perspective of an ambitious young officer in the ISI, meticulously rehearsing a hybrid dialect half Islamabad and half Sandhurst.

We’re all of us—writers, actors, directors, designers—hoping for that “ah” of recognition from an audience. Making the world we thought we understood, new.

When responsible to real situations, our urge to explore the whimsy of character is necessarily tempered by the desire not to distort the world in which these important, history-making events take place. But, I wonder, should it really be any different when working on a Moliere or Shakespeare?