Emily Mann on Bringing the ‘Gumbo’ of New Orleans and A Streetcar Named Desire Back to Broadway

About the Author:

Emily Mann made her Broadway debut as both writer and director of Execution of Justice in 1986. She repeated that feat in 1995 with Having Our Say, for which she earned two Tony nominations, and went on to direct the Broadway premiere of Nilo Cruz’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Anna in the Tropics. Mann has served as Artistic Director of the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, New Jersey, for 22 seasons, overseen more than 85 productions, and directed world premiere works by playwrights such as Christopher Durang, Theresa Rebeck, Steven Dietz, Anna Deavere Smith, Joyce Carol Oates and Edward Albee. Early in her career, Mann became close friends with legendary American playwright Tennessee Williams, and a respected interpreter of his works. As she prepares to bring a revival of his A Streetcar Named Desire starring Blair Underwood, Nicole Ari Parker and Daphne Rubin-Vega to Broadway, Mann let Broadway.com in on her colorful and intensely personal history with this American classic.

![]()

This is the first time I’ve ever directed A Streetcar Named Desire, though it’s been one of my favorite plays since I was a girl. I first read it in high school, and I loved it, but when I saw the movie in college I was very upset. It was late at night, and these undergraduates were all laughing at Blanche and cheering on Stanley and I didn’t understand it. I was so upset by that, and it was actually the first thing I ever talked to Tennessee about.

When I directed The Glass Menagerie in 1979, the production got a lot of press because I was the first woman to direct a play at the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis. Tennessee’s brother Dakin came and loved it, and so Tennessee got in touch with me. I was 28 years old—so young, and so in awe of him. We became quite close, but when we first talked, I said to him one night, “Could I ask you what is, to me, an upsetting question about Streetcar?” And I told him the story of seeing the movie in college. He said that that was one of the hardest and saddest things for him about the Broadway production, that audiences would sometimes cheer on Marlon Brando and not Jessica Tandy. He loved Blanche, and he wanted us to be deeply, deeply moved by her destruction. He knew that the tender people, the artists, have to be protected from the brutes, and it all made sense. That was exactly the play I thought I had read when I was in high school.

Every single character in Streetcar, even the doctor who has three lines, is a complex, three-dimensional person. I went down to see Cate Blanchett star in Liv Ullmann’s production at the Kennedy Center and interviewed them; little did we know that we would bond on a deep level. They did such gorgeous work. When I told Liv my history with Tennessee, she asked me if I had ever directed the play myself. I said, “I can’t do Streetcar. I don’t have to. You’ve given it to me.” And she said, “No, this is the one you have to do, and Tennessee is waiting up there for you to do it.”

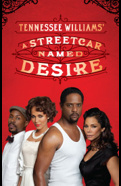

Somehow getting her blessing, and getting the play done in this way, on Broadway, with a cast of color, made it right for me to do now. It was also a way also to dispel the ghosts, because you can’t imitate the geniuses of the past. You have to start fresh.

I’ve wanted to do Streetcar with a cast of color for a very long time. I’m the daughter of an American historian so I love the history of this country, and I love its diversity. Looking at it through this lens—this idea of the gens de couleur, free people of color, those black folks who owned plantations outside of New Orleans and had their own slaves—I’m seeing things that were always there but are coming to the fore, and that’s been quite thrilling.

There’s a slightly different cultural shift that comes from using a cast of color, but at the same time it’s absolutely Tennessee, down to the last period and comma. His first stage direction says a black woman and a white woman are sitting on a stoop laughing, because this is where the races intermingled freely and he was right there surrounded by the culture and music of the French Quarter. Everything down there is just a big gumbo, from people to food, and we’re making it very authentically New Orleans. Once you delve deep into that side of the culture in this play, there’s an ease to it, an effortless quality. It just makes such sense. When you put Tennessee’s language, southern New Orleans language, into the mouths of black actors you think, “Oh my God, they’re black! These characters were written this way.”

In a way, I feel like I’m in communication with Tennessee daily. He always wanted to see a Streetcar of color. In a documentary he once said, “Well, you know, I’m just really black at heart,” and it’s true. He was. He is. He understood human beings, period, and he understood New Orleans society. And you can’t understand New Orleans and the South without understanding black people.

This Streetcar has been full of such serendipity: It’s the right time and the right people and the right cast. This is a glorious cast of actors. Each one is so devoted to the process. They love the play and they love on another, and they know that this is an historic event. When I first met with Nicole Ari Parker I said to her, “Haven’t you always wanted to play Blanche?” And she looked at me through tears and said, “Yes, but I never thought I would have an opportunity.” But here we are. What a wonderful way to honor Tennessee’s memory.

Related Shows

Articles Trending Now

- Curtain Up on George Clooney in Good Night, and Good Luck on Broadway

- Odds & Ends: Dorian Gray Star Sarah Snook and Glengarry's Kieran Culkin Have a Succession Reunion on Broadway and More

- Molly Osborne Is Making Her Broadway Debut as the Desdemona to Denzel Washington's Othello—Maybe Someday She'll Believe It