Learn the Extraordinary True Story of The Elephant Man & How It Inspired Bradley Cooper, David Bowie & More

The Elephant Man is back on Broadway, and no one could be more thrilled than the revival's leading man, Bradley Cooper. The screen star has been enthralled with the true story of Joseph Merrick for decades, and after years of dreaming, he's officially taking center stage December 7 at the Booth Theatre. How did the story of a man with a mysterious illness become the basis for a Tony-winning play? Let’s take a look back at the true story of The Elephant Man.

The birth of “The Elephant Man”

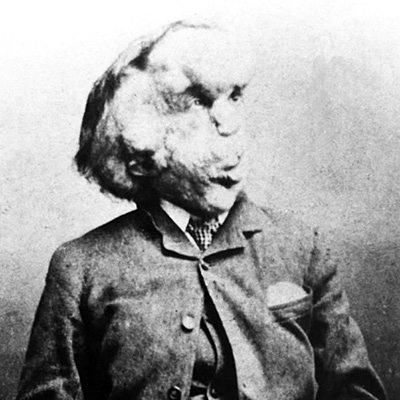

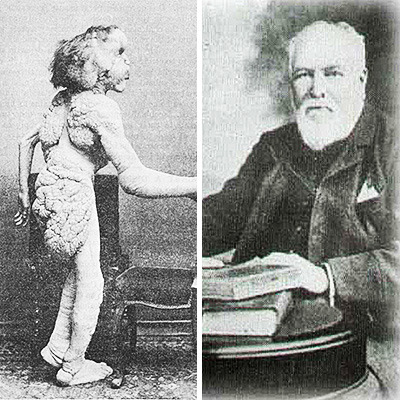

Born in Leicester, England in 1862, Joseph Carey Merrick’s disfigurements first surfaced in early childhood—notably "lumpy, grayish skin" and "a bony lump on the forehead," according to the National Human Genome Research Institute. At the time, Merrick’s condition was rumored to have been caused when his mother was knocked over by a circus elephant during her pregnancy. He is now thought to have had Proteus Syndrome, in which a mutant gene causes atypical growths on the body. (Illustration by Paul Mellor)

Shunned by society

As a teenager, Merrick tried to work as a door-to-door salesman for his haberdasher father, but customers were either scared by Merrick’s appearance or couldn't understand his speech. Merrick’s father responded by beating his underperforming son, who decided to leave home at age 17. After four awful years at the Leicester Union Workhouse, Merrick joined the human oddities circuit as “Half-a-Man and Half-an-Elephant.” In 1884, Merrick was displayed at a shop across from London Hospital.

Saved by a business card

Doctors flocked to take a gander, including Frederick Treves, who examined the young man and presented him to the Pathological Society of London, which Merrick hated—he said it made him feel like "an animal in a cattle market." Treves redeemed himself: In 1886, when Merrick, unable to communicate and in failing health, was picked up by London police, the cops contacted Treves after finding his business card in Merrick's pocket. Treves took Merrick back to London Hospital.

Friends in high places

After London Hospital declined to admit the “incurable” Merrick, chairman Francis Carr-Gomm rallied on the young man’s behalf. He outlined Merrick’s case in a letter to The Times of London, arguing, "He has the greatest horror of the [Leicester Union] workhouse, nor is it possible, indeed, to send him into any place where he could not insure privacy, since his appearance is such that all shrink from him." Support and donations snowballed, granting Merrick a permanent residence at London Hospital.

A bittersweet end

As the hospital staff got to know Merrick, they discovered that he was a kind, sensitive young man, and began to treat him less like a patient and more like a friend. Thanks to his benefactors, Merrick also checked two items off his bucket list: Attending the theater and vacationing in the country. But Merrick’s facial deformities worsened; the size of his head increased and fatigue left him bedridden. Merrick was only 27 when he was found dead on April 11, 1890. It’s likely the massive weight of his head led to death by spinal dislocation or asphyxiation.

Books made Merrick a legend

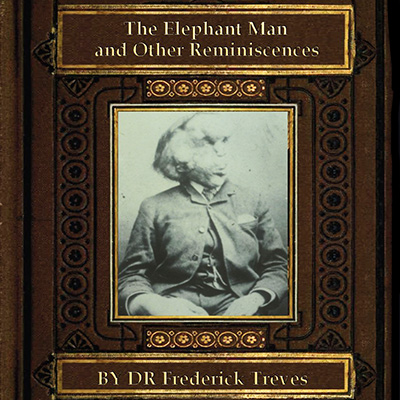

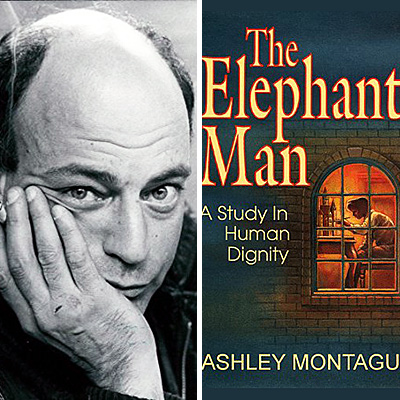

Merrick’s brief, memorable life is the subject of several books, including The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences by Treves, who somehow mistakenly refers to his own patient as “John” Merrick. John, however, was the name of Merrick's younger brother, and according to Ashley Montagu's The Elephant Man: A Story in Human Dignity, Treves accidentally confused the two and the name stuck.

The story piqued a playwright's interest

Bernard Pomerance, an American playwright living in England, first learned about Merrick from his brother Michael, who sent him photocopies of Treves’ memoir and a copy of Montagu's The Elephant Man: A Story in Human Dignity. Pomerance wrote a play in response to Treves’ memoir, referring to Merrick as John, just as the doctor had. The working title? Deformed.

The Elephant Man evolved onstage

Director Roland Rees, who ran a theater company called Foco Novo with Pomerance, needed something for their fall tour. But first, the original title, Deformed—which Rees believed would isolate audiences and producers—was out. They also decided that the actor who played Merrick would not wear makeup. Instead, photos of the real Merrick would be displayed. “They allowed the actor to transform themselves from an ordinary body into a facsimile of Merrick,” Rees told Unfinished Histories.

Broadway beckoned

The Elephant Man opened at the Hampstead Theatre in London in 1977, where it was both a popular and critical success. Of course, Broadway was the next logical destination. After a short off-Broadway run, it bowed at the Booth Theatre on April 22, 1979, starring Philip Anglim. The New York Times called it “an enthralling and luminous play,” while Time raved that it “nests in the human heart.” The show nabbed the Tony for Best Play, and in 1984, a TV movie based on the drama aired on ABC, with Anglim reprising his role.

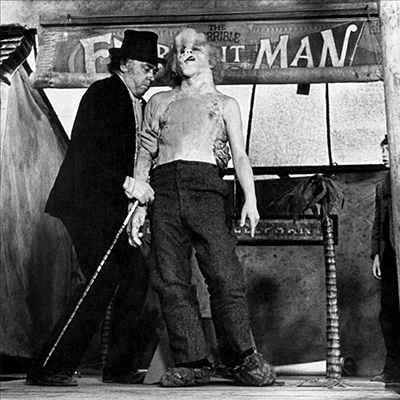

Stardust, Skywalker & more took a turn

The juicy role of John Merrick quickly became a magnet for big-name stars: David Bowie (left) and Mark Hamill, at the height of his Luke Skywalker-inspired fame, were among the leads in The Elephant Man’s two-year run on Broadway. Billy Crudup (right) garnered a Tony nomination in the short-lived 2002 revival. “This character is one of the most hopeful characters I’ve played in a long time,” Crudup told the Associated Press.

Merrick became a Hollywood star

David Lynch’s 1980 movie The Elephant Man is not based on Pomerance’s play, but on Montagu and Treves’ books. Unlike the play, John Hurt, who played Merrick, was covered in detailed makeup. "We were working 20 hours a day," Hurt explained in The Terrible Elephant Man Revealed—it took 12 hours to create the finished look. The hard work paid off: The film, produced by Mel Brooks, garnered eight Oscar nods and introduced the iconic phrase “I am not an animal!” into the pop-culture mainstream.

Bradley Cooper found inspiration

The future Silver Linings Playbook star was 12 years old when he was first introduced to Merrick via the 1980 film. “Lynch created a character with John Hurt that was sort of innocent and beautiful and effortlessly benevolent, and there was something so moving about him, given all of his adversity, that just crushed me as a kid,” he told The New York Times. “I just felt so akin to him.”

Merrick became an obsession

Years later, at the Actors Studio Drama School, Cooper discovered Pomerance's play. He performed The Elephant Man for his master’s thesis—against his advisers’ counsel. To prepare, Cooper traveled to London after buying a plane ticket from his earnings working the graveyard shift at Morgans Hotel, notes The New York Times. Among Cooper’s stops: the hospital where Merrick was treated and the store where he was exhibited.

Back home on Broadway

Alessandro Nivola (Treves) and Patricia Clarkson (high-society admirer Mrs. Kendal) joined Cooper to headline a production of The Elephant Man at the Williamstown Theatre Festival in the summer of 2012. Now, the stars are reprising their roles on Broadway at the Booth Theatre, the same stage where it first opened in 1979. “If you asked me what would be the one character and the one play I’d love to do on Broadway, it would be this play," Cooper told Broadway.com. Adds Clarkson, "You see Bradley become the Elephant Man in front of your eyes.” See the transformation for yourself at the Booth Theatre!