The Visit Scribe Terrence McNally on Avoiding Writer's Block, Choosing Collaborators & Getting Dirty with 'Theater Dust'

The Visit marks Terrence McNally’s 22nd Broadway production. He wrote the book for the Tony-nominated musical, which features a score by John Kander and the late Fred Ebb. The writer, who is the recipient of the Dramatists Guild Award for Lifetime Achievement and a Theatre Hall of Fame inductee, glides easily between working on original plays and writing the librettos for musicals. He has won four Tony Awards (Kiss of the Spider Woman, Love! Valour! Compassion!, Master Class and Ragtime). Here, McNally invites us into his art-filled Greenwich Village apartment to talk about the joys of collaboration and why he never suffers from writer’s block.

What are some essential items you like to have on hand when you write?

A full glass of ice water. That’s about it. Just tap water all day, but it has to be iced. It’s from growing up in the South without air conditioning, I guess.

What time of day do you get your best work done?

No particular time. I just turn on the computer and do the work.

What’s the first thing you do when you sit down to write?

I don’t have any rituals. I just put my fingers on the keys. It’s like second nature. I don’t think about brushing my teeth or shaving—it’s just something I do. I don’t have a need for preparation. I don’t turn on the computer before I know what I’m going to write. I don’t believe in staring at a blank screen. Sometimes I jot things down, but I don’t keep a notebook. I tend to remember good ideas.

What’s the secret to being so prolific?

I live in a fascinating city at a fascinating time in history. When people say they have writer’s block, I say, “Go take a walk around the block! Read the paper! Open your window!” How can you have a block when there’s so much going on? I love what I do, so I don’t think of it as a job that you finish. It’s like breathing.

How do you know when you’re done with a draft?

I just know when I’m done with a draft. There’s no point in showing someone an absolute first draft. I certainly can’t write with people looking over my shoulder. What I very often do is invite friends who are good actors over to sit and just have them read it cold. You can sort of tell if it’s alive or if it’s dead or if it’s got energy. It doesn’t even have to be particularly well cast. I remember the first reading we did of Frankie and Johnny. Stockard Channing read Frankie, and she hadn’t read the play. On about page six, she said, “Oh, shit! She’s a waitress!” She had started reading it like the performance she was giving in Six Degrees of Separation—not like she was playing a coffee shop waitress. You could still tell if the scene had life.

What most appealed to you about working on The Visit?

Working with John and Fred. It’s also a story that I cared about. It’s a musical that makes you feel but it also makes you think, and it raises really important moral issues. It’s one of the most beautiful scores John Kander has ever written. So there was a lot that was appealing in the mix. I never doubted the show would get to New York. It’s too good not to be here.

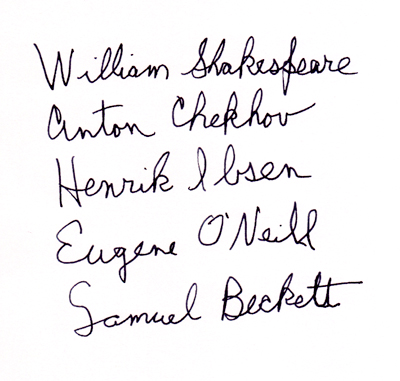

What writers inspire you?

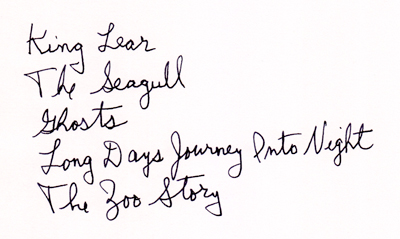

What book or play do you reread the most?

There are several: King Lear, all the Chekhov plays, Antony and Cleopatra and The Tempest. Hamlet is a play I see a lot, so I don’t have to read it as much. I was very lucky I had a teacher in high school that made Shakespeare friendly, so I was never afraid of Shakespeare. If he’s the only playwright you ever read, I think you can learn all you need to know about playwriting. I know people are usually a little surprised when I say he’s the playwright I’ve learned the most from, but learn from the best! If I were a composer, I’d be studying my Bach. I mean I go to contemporary theater all the time, and I love contemporary writers. But I learn from Shakespeare.

What is the most important thing to keep in mind when adapting a work?

You have to respect the tone of the original. I would hope Dürrenmatt would approve of what I’ve done with The Visit. It’s a very bold adaptation—I’ve made it a love story. A play just about revenge is not very interesting for an actor or an actress to play. To me it’s Romeo and Juliet grown up—what would have happened if they got to live to their 80s. The script Dürrenmatt wrote is very poetic, expressionistic—there are talking animals and talking trees. I didn’t like any of that, but I saw a great love story. When I did Ragtime, I showed my treatment of it to [novelist E.L.] Doctorow. If he hadn’t liked it, I probably would not have gone ahead with it.

What advice do you wish your younger self had followed or been given?

I got such good advice on my second play. I got it young. It was from Elaine May. She said, “I don’t care what your characters are saying. What are they doing?” At first I was very insulted by that. I mean that’s what a playwright does—he writes dialogue. The play was called Next. It was very successful. Jimmy Coco did it. I learned from Elaine that a playwright has to know what his characters are doing. If you know what they’re doing, then the dialogue follows as surely the day, the night as Polonius says. And that’s true. People don’t sit around and talk to one another in real life. They are doing something. That’s what the playwright’s job is and that’s where Chekhov is really important—the unconscious, the subtext of a scene.

What play(s) changed your life?

What’s the greatest lesson you’ve learned from working with Kander and Ebb?

Choose your collaborators as carefully as you choose a life partner because you’re going to spend what will seem like a lifetime with them. You better enjoy each other’s company and enjoy each other’s work a lot.

What should all aspiring writers should do?

I think they should go to the theater as much as they can. I know for young writers, tickets can be expensive, but there are programs that get you in at less of a rate. I think you learn the most about theater by going to it and doing it. People say, “I need an agent.” No! You need to write a play. If you’re serious about playwriting, stay in New York City or maybe Chicago—that’s a theater town. Seattle’s a bit of a theater town. L.A. never feels like a theater town. I know there’s theater, but it seems to be what people do between getting booked in a movie or TV show. Hang out with other theater people. Surround yourself with people who are better and smarter than you. You don’t learn anything by always being the smartest guy in the room.

What’s the nitty gritty hard work of being a playwright no one ever told you?

For a musical it’s the rewrites. The composer might say, “I can’t cut a bar or I’m not adding a bar.” Suddenly you only have 18 seconds to that. That I didn’t know until I did musicals. Most people don’t know what a profound collaboration theater is. You can have the best script in the world, but if Shakespeare had had lousy actors, those plays never would have been written—or they would have disappeared. You don’t have parts like King Lear and Hamlet unless you have an actor to inspire you to write them. I’ve been very lucky that I’ve worked with such great actors. The more your hands are dirty with theater dust, the better you’re going to be. It’s not an ivory tower profession. A poet, a novelist, an essayist—they can all live in their lily white pure kingdoms and only deal with one editor. A playwright deals with everyone that enters the room. If you don’t enjoy the real, practical rough and tumble of bouncing off your fellow human being, you’re not going to enjoy working in the theater.

What’s your favorite line in The Visit?