An Act of God Scribe David Javerbaum on Comedy Gods, Daily Show Lessons & Almighty Tweets

(Photo: Caitlin McNaney)

David Javerbaum says he’s the “adaptor” of Broadway’s An Act of God (claiming the Almighty wrote the text), but we’re going to go out on a limb and call him the author. Javerbaum is a 13-time Emmy-winning former head writer and executive producer of The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. He is the co-author of America: The Book and Earth: The Book and the sole author of The Last Testament: A Memoir by God and What to Expect When You’re Expected: A Fetus’s Guide to the First Three Trimesters. His Twitter account @TheTweetOfGod has nearly two million followers. He is also a Tony-nominated lyricist who co-wrote the musical Cry-Baby. He also co-wrote the opening number of the 2011 Tony Awards with Adam Schlesinger and the opening number of the 2016 Tony Awards with Gary Barlow. Broadway.com caught up with Javerbaum at the Booth Theatre just as An Act of God, starring Sean Hayes, opened on the Great White Way.

What time of day do you get your best work done?

I don't have the regularity I should have as a writer. I don't have a time of day or time of the week or a time of the month. The time restraint I need is that of a deadline. If I'm being made to do something I will do it. I've learned over time to put myself in positions in which I have no choice but to write something.

What's the first thing you do when you sit down to write?

I just think about the task that has to be done. I think about the specific context. I like to think of it as a process of discovering what was already there rather than creating something from scratch. I know that sounds pretentious.

Where do your best ideas come from?

I could be anywhere and then something clicks in my subconscious or unconscious. It just pops into my head and all of a sudden its there. I know one thing that happens to me when writing a joke is that the joke will pop into my head and pop out of my mouth completely correctly. Every time I repeat it, it gets worse and worse. That’s because I'm putting more of my intellect and second thoughts into it, where the first pass was the instinctive, correct, unthinking verbiage. I've tried my best over the years to be more instinctive and not to overthink too much.

What inspired An Act of God?

It was based on two previous things of mine: One being the book and one being the Twitter account that stemmed from the book.

Which came first?

The book—or the idea of the book. The Twitter account started as I wrote the book and by the time the book came out, the Twitter account had already developed a following. It developed more and more of a following over the subsequent years. Jeffrey Finn, the producer, approached me and said he’d love to put those things together into a play for a star of some kind. So that was the basis for it. Then I retired the Twitter account for reasons of personal sanity.

Did you write drafts for your tweets?

No, but I would often delete tweets very quickly if I didn't think they would get enough hits. One thing about Twitter that is both a blessing and a curse: It is very easy to get a metric of how it's doing. You can do a statistical analysis of it, which is a very rare thing in the world of writing comedy. Usually, it's a more subjective thing, but that's very objective.

Which writers inspire you?

What was on your mind as you were writing this play?

I was thinking about making it something that—even though I knew I was going to have to be essentially a monologue—had an arc. It needed that to be an alive theatrical experience. It had to have a shape and a character that changed over the course of it. And it had things that made you feel like the equivalent of being in the presence of God in some way. And I knew that if God came down in the form of Sean Hayes and actually did this play, the budget per night would be 10 trillion dollars, given what God could actually do. So how then it was: What do you do to maintain the tension of the night that's produce-able but also feels like there's some kind of powerful force on stage—even with someone seemingly benign looking as Jim Parsons or Sean Hayes.

How did you decide to solve the problem?

With audience interaction—with having two angels, one of whom goes through the audience as the spokesmen of humanity. It gradually goes from a friendly back and forth to a more hostile back and forth, where God takes his anger out on the angel and vicariously on humanity.

What play changed your life?

You’ve had a terrific career in comedy writing. Were you a funny kid?

I was always inclined to at least try to be funny. As the years went on, I was lucky enough to get paid to do it professionally. It became a muscle, and I became better and better at it and my hit-to-miss ratio got better. I learned to rewrite and to cut. One of the many lessons I learned from The Daily Show specifically is that jokes are not my children: they can be killed. I'm not attached to anything. If something doesn't work, you just cut it or you change it. I just want the overall thing to work.

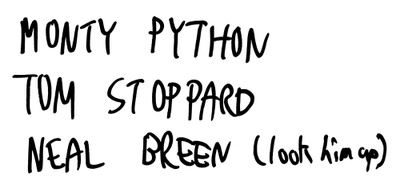

Who are your comedy gods?

All the usual suspects: I think. Monty Python, Steve Martin, Matt [Stone] and Trey [Parker]. I've recently fallen in love with Tim [Heidecker] and Eric [Wareheim]; I think they're amazing. Bill Murray—all those guys. People I've worked with: Jon Stewart, [Stephen] Colbert; they're not gods because I know them, but that makes them even more impressive.

What’s the best piece of advice you've ever received about writing?

A general one that everyone knows is the ultimate truest thing: Show, don't tell. That is the ultimate thing. If you can show something rather than telling it, then you're engaging the mind a spirit of the audience in a way that telling doesn't.

What's the nitty, gritty hard work of being a writer no one ever told you?

That it’s just a whole lot of getting nothing done. It's amazing how much of the time I spend writing is actually writing: It's about one percent. I'm also amazed at how much of it is failure.

What's something you think all aspiring writers and comedy writers should do or see or think about?

I think in one way or another they need to allow their work to be seen and criticized and beaten down until they realize—after years—that you are not your work. Also, you will realize that you can write something that's not perfect and it doesn't mean you're not a good writer. Once you can separate yourself from your work a little bit, it improves both you and your work.

What's your favorite tweet of God?

"Never let the fear of failure keep you from failing."

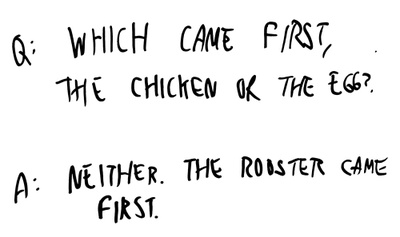

What’s your favorite line in An Act of God?

Related Shows

Articles Trending Now

- 2025 Drama League Nominations Announced; Idina Menzel, Helen J Shen, Nicole Scherzinger, Lea Salonga and More Up for Awards

- Tony Winners Wendell Pierce and Sarah Paulson Will Announce 2025 Tony Nominations

- Redwood, Starring Idina Menzel, Will Release an Original Broadway Cast Recording in May; Debut Track Out Today