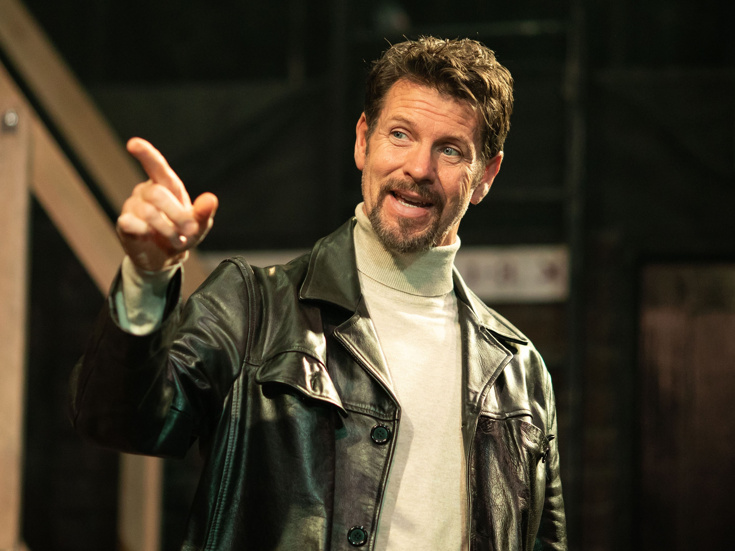

West End Star Lloyd Owen on Heather Headley, Renée Zellweger and the Joys of Noises Off

(Photo: Helen Maybanks)

Lloyd Owen has one of the best, most resonant speaking voices in the business and has leant his vocal luster to such roles as Nick in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, opposite Diana Rigg, and as Heather Headley’s West End co-star in The Bodyguard. He can currently be found as the sonorous (and philandering) director, also named Lloyd, in the latest West End revival of Michael Frayn’s ever-giddy and glorious Noises Off, for which the warmly engaging Owen was in rehearsals at the Garrick Theatre when Broadway.com phoned for a chat.

Have you been part of Michael Frayn’s now-classic and often-revived 1982 farce before?

I was taken to the original production by my mother when I was about 14 or 15. I remember particularly the shock of Lloyd, the director [of the play-within-the-play], shouting from the auditorium, which can be a real moment if you’re not expecting it. I thought, “Christ almighty, someone’s causing trouble in the stalls.”

Did you have any idea that several decades later, you’d be playing that same role yourself?

No, but in fact between that first [Noises Off] and now, I’d seen the previous production at the Old Vic, which I’d really enjoyed. The play feels to me like such a love letter to the theater: you really feel that Michael loves actors the way he’s written them, and it’s the same with the director.

Are you basing the director you are playing on any directors you have worked with—or, indeed, the director of this production, Jeremy Herrin?

Perhaps it depends on the level at which you as an actor have been abused in the past by directors as to where you pitch this performance [llaughs]. I did say to Jeremy, “Obviously, I’m going to base my whole performance on how you behave yourself in the rehearsal room.” The thing about this role is that Lloyd can feel a bit one-dimensional but if you can find the sardonic humor in the part, it better represents what’s written—that and a certain vulnerability.

What about Lloyd Dallas’s look, which strikes me as purposefully unkempt?

Yes, there’s something about that era of directors back in the 1980s and ‘90s who didn’t really care what they looked like. They were full of ideas and less interested in how they appeared to the outside world, so I’ve gone for that kind of dishevelment.

Given that you are seen during the play coming up through the audience, have you ever had any chance encounters?

I did hear my mother-in-law, who is French and quite eccentric, speaking out from the stalls saying, “Lloyd has such a loud voice; it’s so nice to be able to hear him.” I just had to carry on.

Given your character’s capacity for keeping several women on the go at once, does the material perhaps land differently in our #MeToo era?

You have to realize with the Lloyd-Poppy-Brooke love triangle, I think, that both women are really attracted to him; they’re not doing it under pressure. Sometimes there is something about a slightly older man and a younger woman that happens in the real world but to your wider point, I’m not sure that some of that old-style bullying would be accepted now. At the same time, there’s always going to be a power dynamic in the theater where the director is your potential employer.

How have you been coping with the mechanics of the play, in which the middle of the three acts is basically an extended—and physically demanding—piece of backstage business? [This production was first seen earlier this year at west London’s Lyric Hammersmith, site of the play’s premiere in 1982.]

There is a degree to which this play is a machine with very strict parameters as to what you can do: there are certain times where you have to open doors and have sardines [laughs]. But what you really need with this play is a group of actors prepared to check their egos, as it were, and who understand the theater—who know where the joke is.

Can it be tiring to perform?

With anything this physically rigorous, you’re always going to feel slightly under-rehearsed. But I felt very reassured that Jeremy had directed the play before [on Broadway nearly four years ago] so he knew how to make it work in the time frame we had. This play is a feat of engineering where you need your math brain and your engineering head: it’s exhausting to rehearse and wonderful to perform.

At this point, do you recognize the landscape of the play, which honors a bygone English tradition of touring theatrical repertory, not to mention the kind of sex farce you don’t find anymore?

I think the last farce we had on the West End even remotely of this kind was Boeing-Boeing. But I think there’s something about the nature of farce that gets an audience: I’ve never heard people laugh as loud and as long as they do at this play. I did some regional repertory when I first left RADA [the prestigious London drama school], but the sort of twice-weekly rep on view in this play was almost dead even by that time.

How do you think back in your appearance here in The Bodyguard, a show that must have taken you by surprise?

It’s funny—I can keep a tune but I’m in no way a musical theater actor. As you sometimes find with [the shows of] Sondheim, I’m an actor who can sing a tune rather than a singer. I get lots of offers assuming that I sang all the songs as the bodyguard, which would have been a really shocking musical if you think about it.

Were you amused, in a way, to find yourself sharing a stage with a dynamo like Heather Headley?

People were, like, “you’re this macho cool dude and when you sing, you sound like a seven-year-old.” There was Heather smashing out “Queen of the Night” with the band and then me with this reedy little voice.

Not when you speak! Were you aware early on of having an unusually commanding voice?

Yeah, I’m very lucky with that one, which is down to a mixture of genetics and training. To me, it’s not about volume but about thinking of the last person at the back of the stalls: it’s a desire to be heard emotionally.

Shifting just briefly to your film work, I wonder what you make of the current Oscar buzz surrounding Judy leading lady Renée Zellweger, with whom you appeared in the 2006 film Miss Potter?

I really liked Renée, and she’s such a hard worker. That’s the thing you realize about the Hollywood mob: they don’t get there by mistake. It’s a lot of pressure to keep going, particularly if you’re a woman, and Renée was an absolute professional: a total pro.