The Irishman Oscar Nominee Al Pacino Has Been on Broadway a Dozen Times

(Photo: Emilio Madrid and Jeremy Daniel; Design by Ryan Casey for Broadway.com)

Al Pacino just received his first Oscar nomination in 27 years for playing Jimmy Hoffa, and getting de-aged, in Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman. And while the Oscar winner’s roles in The Godfather, Serpico and Dog Day Afternoon have placed him among the most recognizable and prolific actors of the past 50 years, in between his powerhouse film roles, Pacino has routinely returned to the Broadway stage to test his craft. Pacino has appeared in 12 Broadway shows, won two Tony awards and received nine Oscar nominations (including Best Supporting Actor in The Irishman).

This week, Broadway.com is taking a look at the stage careers of a few of this year’s nominees, including Adam Driver, Jonathan Pryce, Scarlett Johansson, Cynthia Erivo and Antonio Banderas. Some started off in theater, others were film stars first, and a few regularly travel between stage and screen. For more on this year’s theater-friendly Oscar nominees, look here.

Below, a look at Pacino’s most formative Broadway credits.

Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie? (1969)

Pacino’s career began in the theater. Born in East Harlem in 1940, Pacino attended the High School of Performing Arts in New York City and studied with Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio. He won an Obie Award for Best Actor in 1968 for an off-Broadway production of The Indian Wants the Bronx. In 1969, he made his Broadway debut in Don Petersen’s Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie? Pacino played Bickham, a sadistic and psychotic drug addict at a rehabilitation center. While the play lasted only 39 performances, critics proclaimed Pacino the breakout star of the season. Clive Barnes wrote that he was the “best young actor in town” in his New York Times review; Pacino was awarded his first Tony that year. It was only three years later that Pacino landed the monumental role of Michael Corleone in The Godfather. Of his Broadway debut, Pacino said, “"It was a whirlwind-experience, it led directly to my first film, Panic in Needle Park, The Godfather, and then, Serpico."

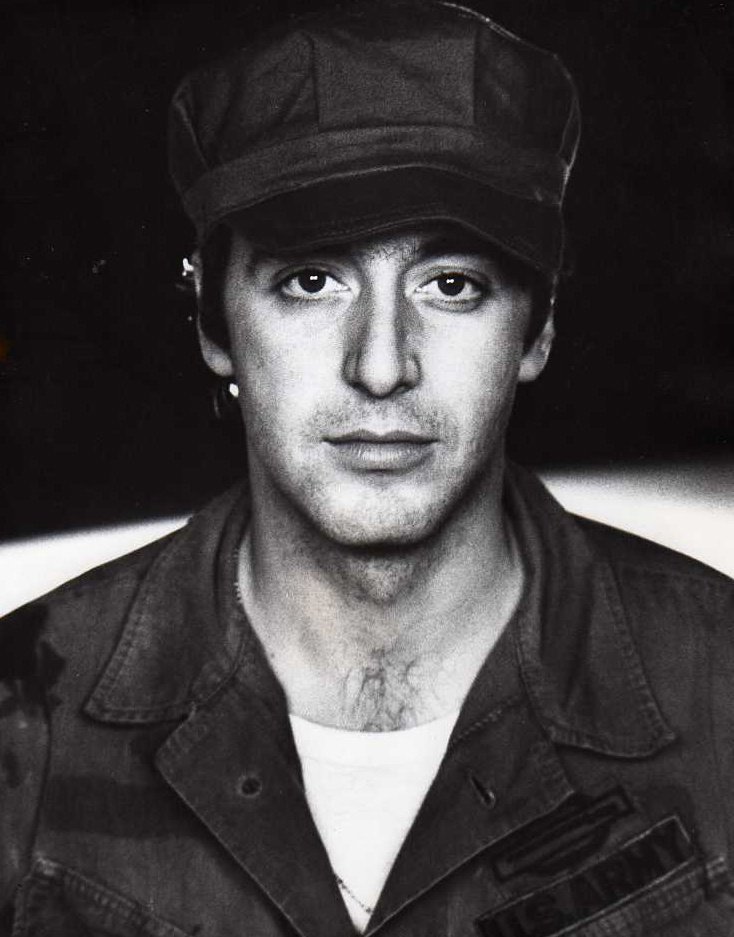

The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel (1977)

Pacino’s second success at the Tony Awards came in 1977, when he played the title role in David Rabe’s searing anti-war play, The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel. Pacino’s character was an enthusiastic soldier who gets himself killed during the Vietnam War. Audiences flocked to the Longacre Theatre to see the film actor, who at that point had been nominated for four Oscars. His turn as Hummel earned Pacino a second Tony Award.

American Buffalo (1983)

Pacino played the title role in King Richard III (1979) next—a role he first mounted in Boston in 1973 and later adapted into the 1996 documentary film Looking for Richard. Then, in 1983, the actor starred in the first Broadway revival of David Mamet’s American Buffalo, about a group of hustlers trying to steal a cache of rare coins. The play and Pacino’s performance began a long artistic partnership between Mamet and Pacino, one that burgeoned two other Broadway productions: a 2012 revival of Glengarry Glen Ross—the 1992 film adaptation also starred Pacino—and China Doll in 2015. “The relationship and the collaboration with David Mamet has been one of the richest and most rewarding,” he told The Hollywood Reporter in 2014. Mamet wrote the character of billionaire Mickey Ross in China Doll for him and Pacino called it, “one of the most daunting and challenging roles I’ve been given to explore onstage.” Mamet himself called the short-lived play “better than oral sex.”

The Merchant of Venice (2012)

In 2012, Pacino led a Broadway production of The Merchant of Venice as Shylock, reprising a Shakespearean role he brought to the screen in Michael Radford’s 2004 film adaptation. Shylock earned him a Tony nomination and showcased Pacino’s love of the classics—Pacino also starred on Broadway in Eugene O’Neill’s Hughie (1996) and in two productions of Oscar Wilde’s Salome (1992, 2003). “[Bertolt] Brecht, as well as Shakespeare, really helped me in my life. Also Henry Miller, Balzac and Dostoyevsky,” biographer Andrew Yule quotes him as saying. “They got me through my twenties, gave me such a raison d’être. The relationships we have with writers are quite a thing. They’re different from the ones we have with actors or musicians or composers or politicians. Everything for me is the writer; without him I don’t exist. An actor gets all the glory, but I don’t know about enduring.”