Gerald S. Krone, Founding Member of Negro Ensemble Company Original A Soldier's Play Producer, Dies at 86

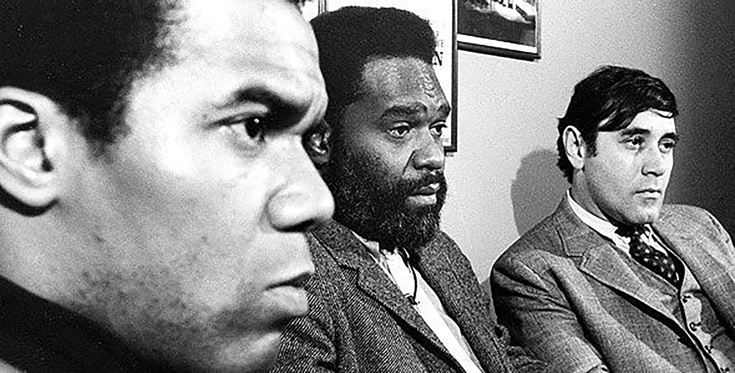

(Photo Courtesy of the Negro Ensemble Company)

Gerald S. Krone, a founding member of the Negro Ensemble Company who joined Douglas Turner Ward and Robert Hooks in building a landmark center for African-American theater, died on February 20 at his home in Philadelphia. According to his longtime partner, Ivan Kaminoff, Krone died from Parkinson’s disease. He was 86.

At a time when black activism was engaged in a new militancy and urgency, Krone joined with playwright Ward and producer Hooks in 1967 to begin the Negro Ensemble Company, which would house and develop work by black playwrights. Taking up residency in the East Village at St. Marks Playhouse, then moving to Theater IV, the Negro Ensemble Company became an influential force in reclaiming the locus of black identity in theater under the pen of black playwrights, developing a canon for African-American theater-making in New York City and a foundation for writers like Charles Fuller and, to come, August Wilson.

Krone first collaborated with Ward and Hooks as a producer on Ward’s plays Happy Ending and Day of Absence in 1965. After Ward published a controversial New York Times article, “American Theater: For Whites Only,” in 1966, Ward, Hooks and Krone began discussions with the Ford Foundation to create and fund a black-centered theater project. The trio proposed creating a permanent acting company and, crucially, a school and training program for every aspect of theater. The Ford Foundation accepted and incorporated NEC with a $434,000 grant (more than $3 million in today’s money). In 1967, NEC began functioning with 13 permanent actors and 125 students and, in 1968, opened its first production to great critical acclaim, Song of the Lusitanian Bogey.

Already an established off-Broadway producer when he met Ward and Hooks, Krone took on a theater managerial role at NEC, credited as managing director and producer for 24 NEC company productions from 1968 until 1981, when Krone left the company to pursue work in television.

Krone, who was born in Memphis in 1933, was white, drawing some criticism from black nationalists who rejected the company’s hiring of several white staff in their downtown—not Harlem—location. “The criticism [of NEC], issuing in the main from a few self-appointed defenders of the black grail, generally questioned the ideological purity of our black commitment and deemed us insufficiently motivated in black consciousness,” Ward wrote in a 1968 New York Times article addressing the founding of, success and controversy surrounding NEC. “Specifically, we were damned for not being located in Harlem, accused of conspiring against black playwrights, judged traitorous for hiring a few white people, and stigmatized with a host of other mortal and venial sins negating our right to be called a black theater.”

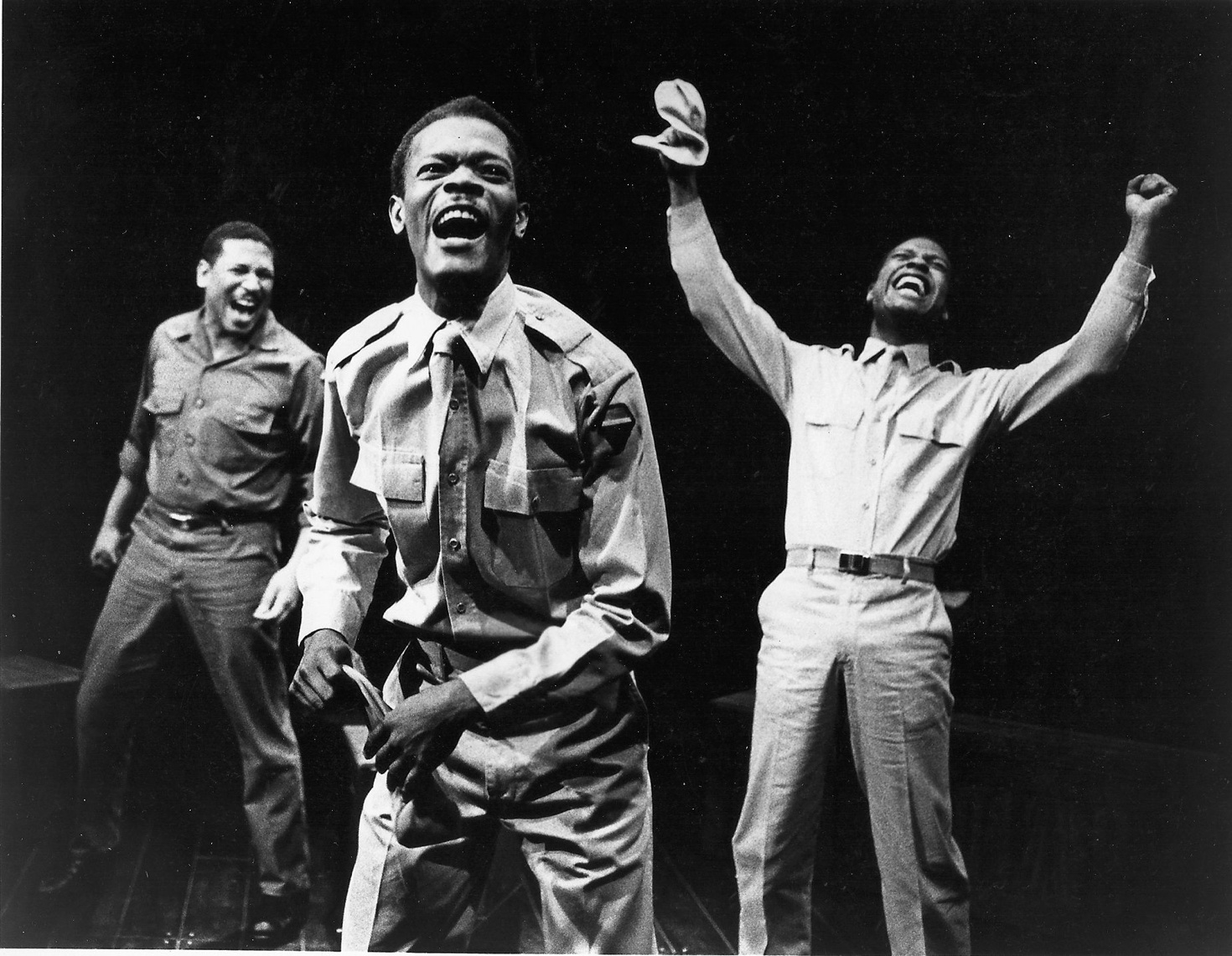

Yet, under Krone, Ward and Hooks' leadership, NEC became enormously successful, transferring three productions to Broadway: The River Niger (1973), The First Breeze of Summer (1975) and Home (1980). The River Niger, which included Ward in a Tony-nominated featured role, was lauded as “one of the best black plays to be seen hereabouts” and awarded the Tony Award for Best Play in 1974. In 1981, NEC staged the first production of Charles Fuller’s seminal A Soldier’s Play, which earned a Pulitzer Prize for drama in 1982 and, this season, makes its Broadway debut starring original production member David Alan Grier.

In 1969, just two years after its founding, the Negro Ensemble Company production received a Special Tony Award, which Krone accepted alongside Ward. “I want to extend my personal thanks,” said Krone in his acceptance speech, “to our students, our actors, designers, directors, staff, to our playwrights and to our black audience for being courageous enough in this rather difficult, confusing, disturbing time to give me, a white man, an opportunity to be a part of a very important, dynamic, wonderful, black theater, which is theirs.”

Krone is survived by Kaminoff, whom he married in 2013 after two decades of partnership, and his brother, Norman.