Harmony's Chip Zien on 50 Years of a Broadway Career & the Four Great Roles That Have Defined It

(Photo: Julieta Cervantes)

Nearly 50 years into a Broadway career, Milwaukee native Chip Zien (born “Jerome Herbert Zien”) took the pandemic as a moment to start stepping back from the stage. So he tells Broadway.com Editor-in-Chief Paul Wontorek from the living room of his Upper West Side apartment for a special career retrospective on The Broadway Show. “And then,” Zien says, “I got a call from my agent that Barry Manilow has a show.”

That show—as Zien and every pedestrian who passes the Barrymore Theatre on 47th Street now know— was Harmony. A collaboration between Manilow, his longtime partner Bruce Sussman and director Warren Carlyle, Harmony unearths the story of the once-famous German sextet, The Comedian Harmonists, who were scrubbed from history by the Nazis. The part presented to Zien was Rabbi, a (nearly) present-day version of the last surviving Harmonist who serves as both a narrator and wayfaring performer of the show’s miscellaneous characters (Richard Strauss and Albert Einstein among them).

By the time Harmony landed on Zien’s doorstep, the itinerant musical had been knocking around for over two decades—but the idea of an older Rabbi anchoring Harmony as a memory play was a brand-new concept. Zien was immediately smitten: “It's funny— but it's serious and it's difficult,” he says about the taxing role that initially left him worried about his own stamina. But the most astonishing element of this proposition, he recalls, was the messenger: “Barry Manilow couldn't possibly know me,” Zien remembers saying to his agent. “But it turned out that he did.”

Chip Zien (center) as Rabbi in Harmony

(Photo: Julieta Cervantes)

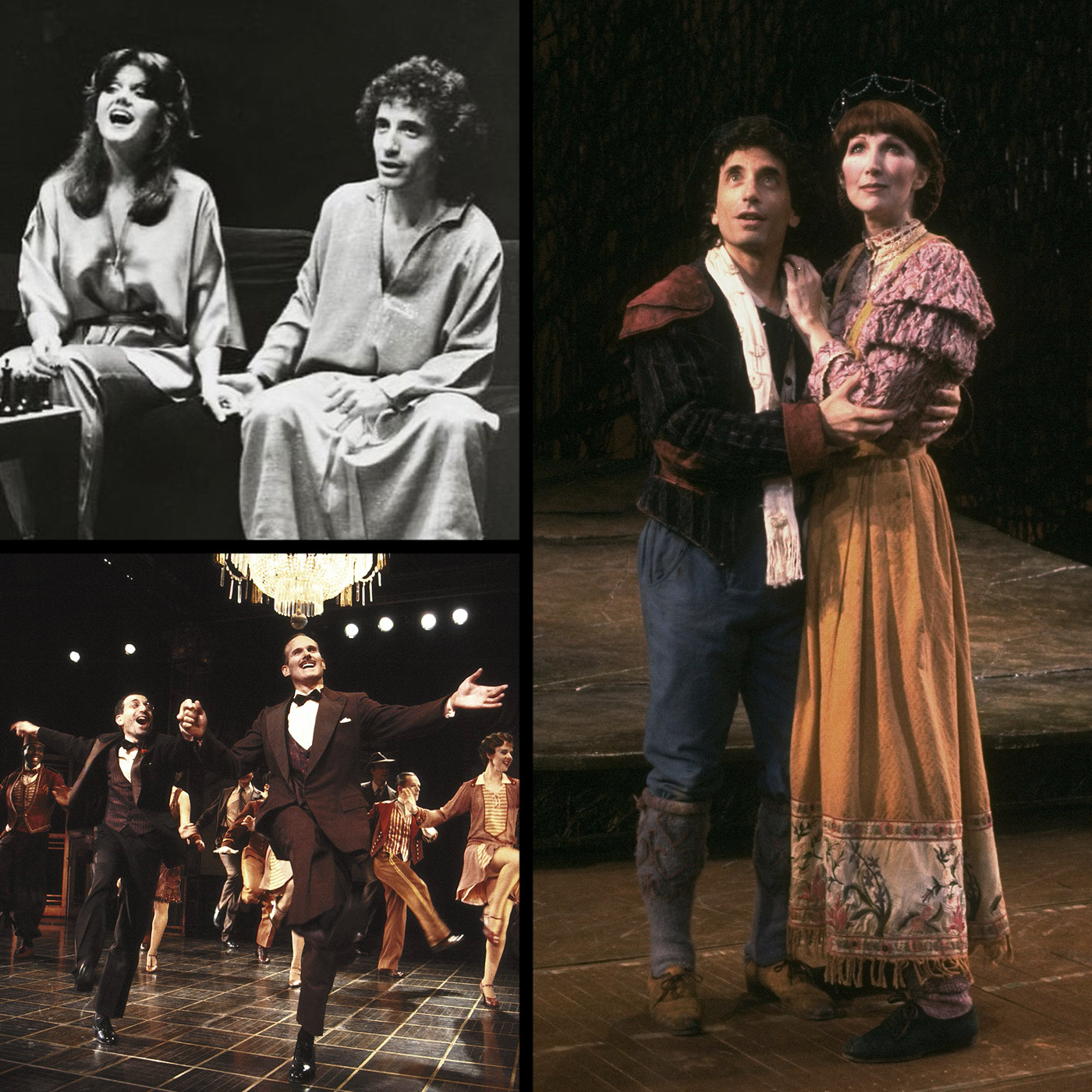

“Chip Zien” may not be a household name of Hollywood stature, but for those with Broadway know-how, his career is one of the most iconic in the business. Zien recounts how the actor Tony Randall once said to him that a stage performer is lucky if he has two great roles in a Broadway career. With a mix of contentedness and gratitude, Zien says, “I’ve had four.”

Most notable is likely the Baker in the original 1987 production of Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s Into the Woods— a performance made famous by the PBS recording on which generations of Sondheim acolytes have come to cut their teeth. It also happens to be the job that determined Zien’s future as a homeowner. “Into the Woods was supposed to come into town faster than it did, and I suddenly got very nervous that I didn't have enough funds to sustain my new lifestyle,” he says, referring to the purchase of the very apartment in which he and Wontorek take their stroll down memory lane. Needless to say, “It worked out.”

Closely following Into the Woods (and in the very same theater, the Martin Beck, now the Al Hirschfeld) came Grand Hotel, one of the most acclaimed musicals of 1990 in which Zien replaced Michael Jeter in his Tony-winning role as Jewish bookkeeper Otto Kringelein (Wontorek betrays his own fandom by greeting Zien in a vintage show jacket). “I was in LA when I got a phone call to come back to do Grand Hotel,” Zien remembers. “I said to my agent, ‘No, I'm out here now. I'm trying to figure out what to do after Into the Woods. And then I went back to sleep…When I woke up, I thought, ‘That's a big mistake.’” Zien’s gut ultimately led him back to New York City where he relished his evenings fox-trotting with Jane Krakowski to Tommy Tune’s Tony-winning choreography. “I loved every minute of it.”

"Barry Manilow couldn't possibly know me. But it turned out that he did."

—Chip Zien

His next great role came in 1992 in the groundbreaking William Finn and James Lapine musical Falsettos—a show that unpacked Jewish identity, elegantly (and humorously) explored ideas of gender and sexuality, and stared the AIDS crisis in the face. Zien originated the role of Mendel, a psychiatrist who ends up marrying his young patient’s mother and becomes an important part of the characters’ unconventional family unit. The kinship extended backstage as well.

“It was such a family event,” Zien says about the lengthy process of molding Falsettos (a two-act musical, which, in its original incarnation, comprised March of the Falsettos and Falsettoland). “Bill Finn is like family to me…We fought and talked and we developed these shows.” The timing of Falsettos, Zien notes, compounded its significance. “The time at which Falsettos landed on Broadway was in the midst of a horrible moment in our history of sadness,” he says. “Many of our friends were not well. It felt more important than any of the normal concerns you have when you're opening a show…It seemed to be greater than that. It was a celebration.”

"I've Had Four." Beyond Harmony, Zien's favorite character turns as (clockwise from top left) Mendel in March of the Falsettos with Alison Fraser, The Baker in Into the Woods with Joanna Gleason and Otto Kringelein in Grand Hotel with David Carroll (Photos courtesy of New York Public Library)

Over 30 years later, at the age of 76, Harmony has been an unexpected addition to this list of career highlights, possibly even taking first position— and on a similarly meaningful cultural backdrop. “We're landing again at a pivotal moment in our politics and in our history,” says Zien, who, as Rabbi, sings the mournful “Threnody” in Act II—a cry of frustration for all that could have been done to fight antisemitic and fascist tide in Weimar Germany, and a lamentation for what was beyond human control.

“This role in particular has become so important to me,” he says, thinking not only about the shows that likely put him on Barry Manilow’s radar, but every one of the potholed inflection points he recounts to Wontorek: His (maybe ill-fated) decision to pass on an offer directly from Bob Fosse; his childhood streak playing all the great roles for leading ladies as the most talented soprano at an all-boys summer camp; and of course, his windfall as the 1986 cigar-smoking superhero Howard the Duck (Into the Woods may have kept him in his apartment, but Howard the Duck was the down payment).

“I was saying to my cousin last night, who came to the show, ‘We're from Milwaukee. How did this happen?’” Zien, a seasoned veteran with a half-century of experience, poses the question with the awe of a newcomer making his Broadway debut.

“I don't know,” his cousin replied. “I watched you grow up. You were just kind of a little guy who was annoying.”