For All the Devils Are Here, Patrick Page Gets in Touch With His Dark Side

(Photo: Julieta Cervantes)

With his commanding physical presence and a voice sent from the most doomed recesses of the underworld, perhaps it was inevitable that Patrick Page would be called upon, time and time again, to play the bad guy: several Shakespearean villains, yes, but also Hades in Hadestown, Scar in The Lion King, the Grinch in How the Grinch Stole Christmas and the Green Goblin in Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark.

What’s also evident in his riveting one-man show, All the Devils Are Here: How Shakespeare Invented the Villain, is that Page is ineluctably drawn to darkness. In the show (whose run was recently extended), Page takes audiences on a chronological tour of Shakespeare’s works, contemplating the playwright’s preoccupation with wickedness while also channeling some of the most tormented, diabolical characters in the canon.

Page recently spoke with Broadway.com about the deliciousness of camping it up, mental health, the nature of evil, and the persistent allure of the abyss. These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

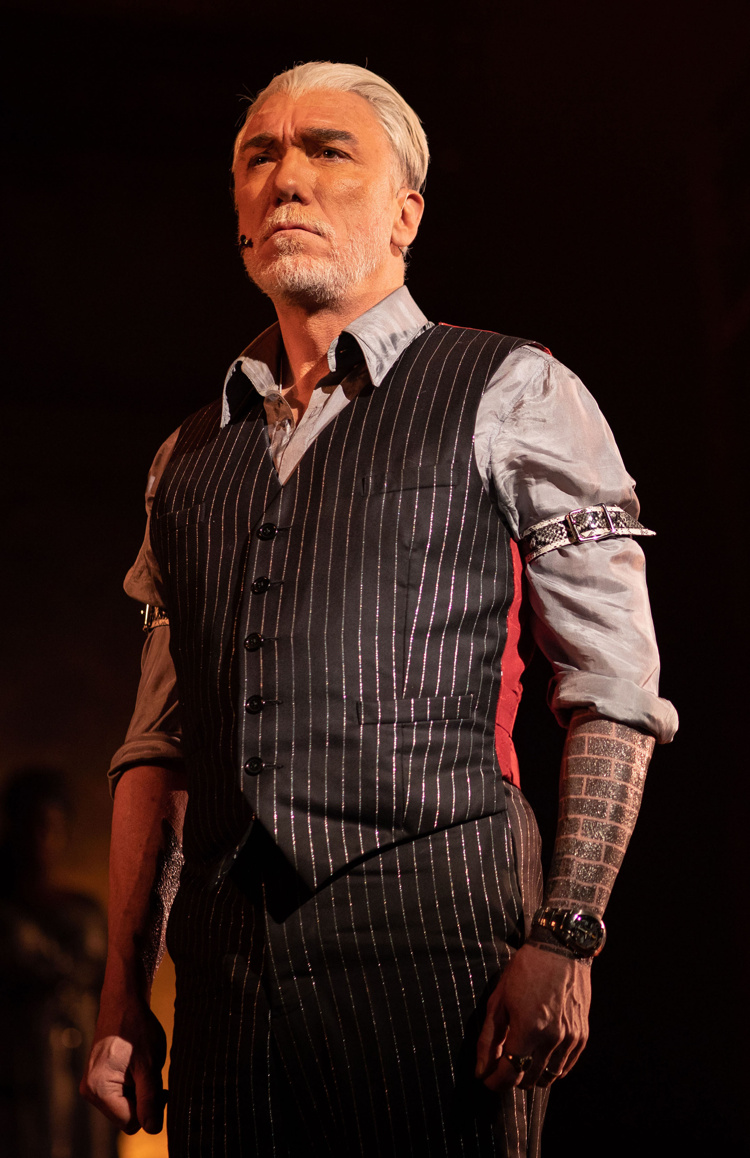

Patrick Page in All the Devils Are Here

(Photo: Julieta Cervantes)

Do you have a good time playing bad guys?

Oh, there's a fun side to it for sure. When you look at the Disney villains, they're all camp: Captain Hook, Ursula, Scar. There's this lack of humility and sense of superiority that is delicious to play... Though it's something to avoid in one's life. Add a diabolical plot to overthrow the world, and then you've got some real fun.

At least one of those Disney villains was directly inspired by Shakespeare. When you're playing Scar in The Lion King, are you also thinking on some level about Richard III and Claudius? Is that part of the potion?

Not while you're doing it, but in the preparation for it, certainly. Richard III feeling so much on the outside of things… Claudius, being the younger brother, that sense of being second best.

The thing about a musical, of course, let alone one based on an animated feature, is that the actor’s toolkit is in some ways curtailed. Scenes are made as brief as they can be so that we can get on with the singing and the dancing. Playing Shakespeare allows you to do something beneath the surface.

"I admire these actors who say they lay the character down and go home. I don't know how quite to do that." –Patrick Page

In one of your go-to Shakespearean texts, Harold Bloom describes Macbeth as an “occult medium dreadfully open to the spirits of the air and of the night.” To me it sounds like the lot of the actor. Do you feel like an occult medium?

Well—oh, it's going to sound so arrogant, isn't it, if I say yes? But yes, when I'm doing what I do well, then it is not coming from me.

Leonard Cohen used to say, “If I knew where the good songs come from, I'd go there all the time.” In the same way, I don't know why last Thursday night I was brilliant and Friday night I couldn't find it, and Saturday night I was okay, and Sunday afternoon I was hopeless... And Tuesday night, I was fucking amazing! I just prepare myself to be the best vessel for whatever will come through me.

Patrick Page in Hadestown (Photo: Helen Maybanks)

What about opening yourself up to darkness? You’ve been very open about your mental health journey. I’m sure there were many factors that led to your breakdown while rehearsing for Hamlet. Was having to become a fratricidal king one of them?

Yes. I mean, that's very perceptive of you—that is the case. I admire these actors who say they lay the character down and go home. Anthony Hopkins is one of those. I don't know how quite to do that.

And at the same time, it’s the work I wish to do for myself and for the audiences. To actually place myself in the imaginative condition of believing the imaginary circumstances of the play, and doing the research and the work necessary to get to that place—it can have a psychological cost.

How do you deal with that?

I deal with it as well as I know how. I go to a shrink once a week. I meditate and pray every day. I read a lot of stuff. I try to stay engaged and talk to people and I don't drink anymore.

There must also be a difference between playing Hannibal Lecter for the camera and living with Claudius or Macbeth for the length of a theatrical run.

Yes, I think that's true. I think the repetition of it is something. But I also think that, in the case of Hannibal Lecter, Hopkins did a very cunning thing there. He didn't portray or go deeply into any kind of clinical expression of psychopathy. He played a boogieman, a nightmare creature—much less like a photograph and more like an oil painting by Francis Bacon. I would've fallen right into the trap of trying to make it medically accurate.

You do immerse yourself in the research. Is a certain level of Shakespearean scholarship essential to playing Shakespeare effectively?

It is, yes, certainly. He was occupied with very, very deep, profound ideas about the nature of reality, the nature of consciousness, the nature of justice, the perils or the prospects of utopia… The actor, in order to play these characters, has to engage as deeply as he or she can with those same questions or you're not going to be able to lift them out of the text.

Patrick Page in All the Devils Are Here

(Photo: Julieta Cervantes)

You were bookish as a child, to the point of being a real misfit. Does that inform how you portray Shakespeare's tortured outsiders?

Sure, absolutely. When I was a kid, I wouldn't play with the other children at recess. I would walk around the perimeter of the schoolyard. I had my own little world. I'm still quite introverted. When my wife is out of town, I can spend three or four days blissfully by myself reading. It’s just my character. It certainly informs a character like Richard. Or the Grinch.

Has studying villainy given you any insights into the nature of evil in the world? And how to process it?

Yes. Shakespeare refuses to write people off. He gets curious as opposed to getting judgmental. He wonders very deeply, “Why might that person behave that way? Under what conditions might I behave in that way?"

Carl Jung said, “One achieves enlightenment, not by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness visible to oneself.” You really have to look deeply into yourself because, as Jung observed, very presciently, we have what he called the shadow—that part of us which we don't want to admit is there. The darkness, the envy, the aggression, the lust, all of that. And we say, “Not me.”

I'm comfortable with the person who says, “Ah, God, I'm a cranky old sinner, but I try to do my best.” I love recovering alcoholics—they all know they're broken. They're not saying, "Ah, I've got it solved."

When I meet someone who identifies themselves as virtuous, that's when I get most frightened.