Craig Lucas and Adam Guettel Reach for Precision and the Ecstatic in Days of Wine and Roses

(Photo: Joan Marcus)

Days of Wine and Roses, now running at Studio 54, is the second Craig Lucas-Adam Guettel collaboration to make it to Broadway. The first, as fans of their partnership remember, was The Light in the Piazza—Elizabeth Spencer’s story of a stunted young woman’s awakening during an Italian vacation with her mother. It opened on Broadway in 2005, earning Lucas a Tony nomination for his book, winning Guettel a Tony Award for his first-ever Broadway score and launching Kelli O’Hara as Broadway’s premier ingenue. Beyond awards, it also introduced Broadway to a new kind of musical—one that embraced the legit vocal style of the golden age but through modern, chromatic melodies, and that leaned into as many ambiguities in its narrative resolutions as in its musical ones.

Twenty years later, there’s still nothing that sounds quite like a Lucas-Guettel project. And for a second time, their approach to their source material—Blake Edwards’ 1962 film (adapted by JP Miller from his original 1958 teleplay) about a marriage and family ravaged by alcoholism—is a reminder of how malleable musical theater can be. It almost makes you forget how fragile musical theater can also be when one ounce of discord between writers can send a project spinning. For a partnership that innovates with such clarity of purpose, it might be surprising to hear Lucas say that he and his most indelible collaborator are “very different people.”

“Adam's personal internal mechanisms are very different from mine,” Lucas tells Broadway.com Managing Editor Beth Stevens for The Broadway Show. Lucas first met Guettel when the composer was just 15 years old. Lucas himself was 30 and working with Stephen Sondheim on Marry Me a Little, a revue of cut songs from Sondheim’s other musicals. Oscar Hammerstein II had been Sondheim’s mentor, and Hammerstein’s writing partner Richard Rodgers was Guettel’s grandfather, so the six degrees of separation landed them in a room together.

"Your job as the book writer is to make every moment, particularly the songs, feel inevitable." –Craig Lucas

“Here we were sitting and talking,” Lucas says, referring to himself and Sondheim, “and Adam sat down and went, ‘I'm not sure I liked that you used sixths in that song. Why did you do that?’ I thought, ‘Do you know who you're talking to?!’” Still, Sondheim took the note from the precocious young musician. “No, you're right,” Lucas remembers Sondheim saying. “I have the same questions.”

“I already saw—oh, for heaven's sakes, who is this child?”

At the time, Lucas was already enthralled with a particular brand of musical theater. “I went to school in Boston, and those were the years in which Hal Prince and Steve Sondheim were bringing all their musicals to the Colonial. So I saw every one of those. And I saw them multiple times because I was so enamored,” he recalls. “Most musicals when I was growing up—with the exception of some of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals—most of them were slight and frothy diversions.” Seeing Sondheim’s work, he thought, “Oh, you can do that in a musical. You can talk about relationships and the world and they can be as dimensional as plays and movies. Who knew?”

It’s likely that a meticulous composer who demands to know the why behind every interval and time signature had a sense of those possibilities. And as someone who also carries a family legacy of shirking the slight-and-frothy aesthetic of the day, it’s evident where Guettel and Lucas creatively meet—even if their creative processes look vastly different.

“Craig writes very quickly,” Guettel says matter-of-factly. “I take forever. I think the first song for this show took about a year.” That six-minute number, called “Magic Time,” follows the prickly but ultimately profound meet-cute between public relations executive Joe Clay (Brian d’Arcy James) and secretary Kirsten Arnesen (Kelli O’Hara) during a boozy yacht party. “That song represents the whole musical vocabulary,” Guettel explains. “My grandfather used to call it the first olive out of the jar.”

As Days of Wine and Roses wended its way from Atlantic Theater Company off-Broadway to its new Broadway stage, it became public knowledge that it took several years for Guettel to even open the jar, let alone pry out its first olive. As the story goes, O’Hara proposed the project as a vehicle for her and James (her recent castmate in the short-lived musical Sweet Smell of Success) during the early Light in the Piazza days. At that time, it was exclusively in Guettel’s hands, and it was 10 more years until he sought out the rights to the property. By 2012, he had done a bit of composing, but it wasn’t until 2015, when Lucas was on board, that the two went away to an arts colony to finally dig in.

“Adam needs a collaborator,” Lucas says. “He needs someone to bounce ideas off and to get excited and help structure things and make the decisions.” Once that bit of scaffolding is in place, however, the work starts to flow. “I've worked with a lot of songwriters and many that I would work with again in a heartbeat. But Adam is of another realm of accomplishment. You're playing tennis with someone who is always going to hit the ball back faster and better than you can. No one understands musicals better than Adam.”

"Music suits this because it is a way of reaching for the ecstatic." –Adam Guettel

Lucas describes his work like an expert technician: “Your job as the book writer,” he says, “is to make every moment, particularly the songs, feel inevitable as if they're just a natural outgrowth of things. I've spent a lot of my life learning to do that.” Guettel, meanwhile, offers a more ethereal account of his composing: “I got to write it on them and sort of drape it on them,” he says of his score, tailor-made for O’Hara and James. As poetic as he is particular, he forgoes an explanation of grounded mechanics in favor of the sublime. “Music suits this because it is a way of reaching for the ecstatic—which is unfortunately what alcohol allows people to do for a while until it sends them in the complete other direction.” He calls his music for Days of Wine and Roses a “contradictory scream”—a desperate call for something life-affirming that is ultimately destructive.

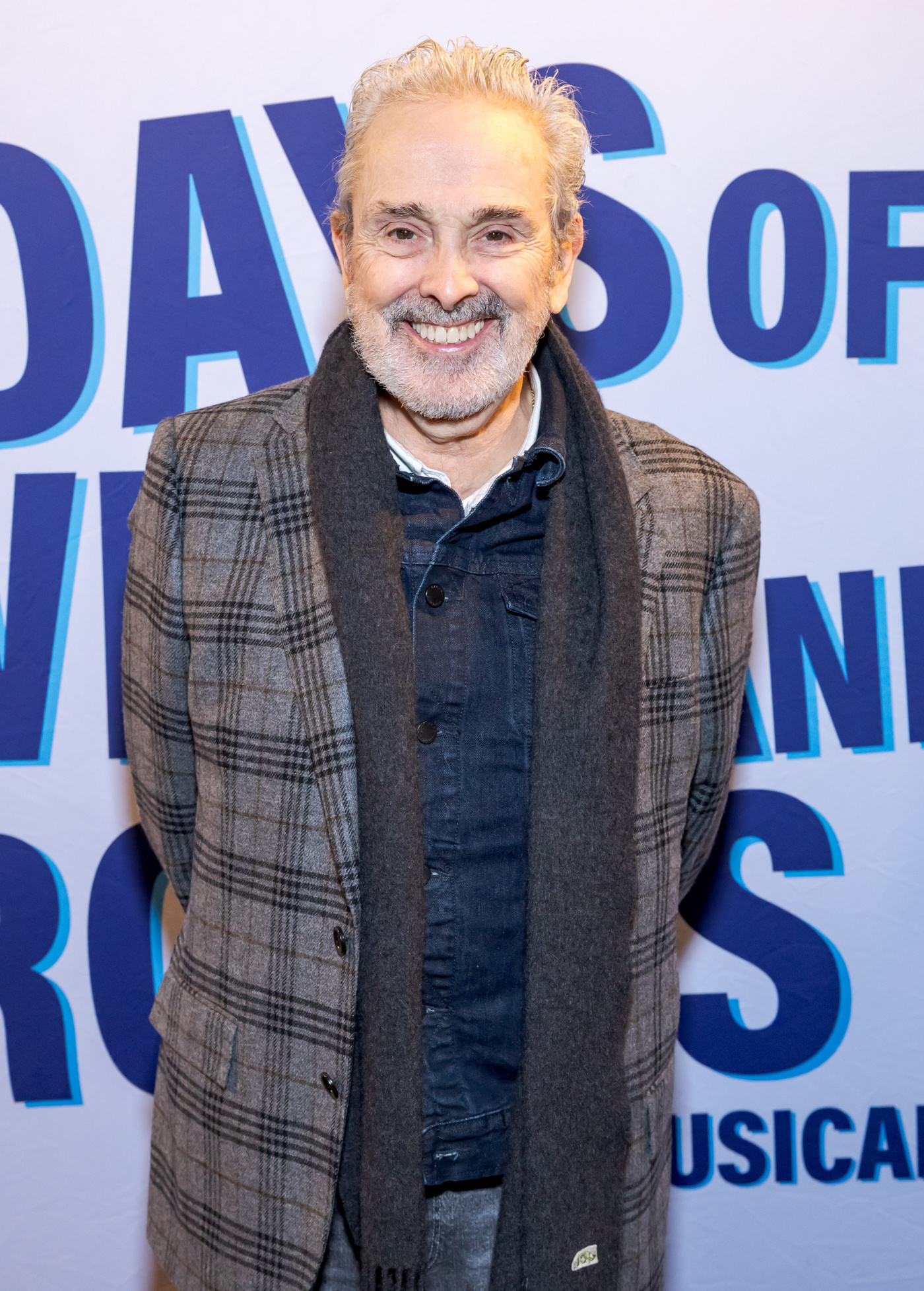

(Photo: Rebecca J Michelson)

“When we're in a room at the formative stages of writing something, we feel very safe with each other,” Guettel says about his collaboration with Lucas. “It's a very fluid environment. We've both done this for so long and with each other that we feel safe to propose things, many of which have not ended up in the show. But we come through that creative thicket, usually unscathed.”

“It's my favorite part of the process,” Lucas asserts about this sequestered writing period. “That part when you're dreaming something up is the most exciting and fulfilling part in many, many, many ways.”

Once the piece got in front of its stars, it went through new rounds of scrutiny: “Why is this comma here? I don't understand why this word is in the end of the sentence and the beginning of the sentence. Does this belong here?” Lucas recites, relating a few of O’Hara and James’ rehearsal-room interrogations. “They make you work really, really hard, which is what you want.” A mention of director Michael Greif is also met with a chuckle from Lucas. “Michael is like the laser microscope on everything.”

Still, since Lucas and Guettel’s first Sondheim-facilitated encounter over 40 years ago, fastidiousness and transcendence have peacefully coexisted. That confluence of qualities is likely what makes their partnership what it is. And of course, there’s the all-important element of loyalty. “Loyalty really is why we're here,” Guettel claims, considering all the people who followed Days of Wine and Roses through its long, contemplative gestation. “The piece is sort of made of loyalty and booze”—like Lucas and Guettel, a classic Broadway combination with a twist.