In Doubt, Zoe Kazan Explores the Mysteries of Life and Acting

(Photo: Joan Marcus)

At first glance, it might occur to you that the actor and writer Zoe Kazan has the wide, watchful eyes of a deer caught in the headlights. Look again, and that same gaze may take on the probing, interrogative quality of a pair of military searchlights. Maybe she's the one about to dispatch the deer.

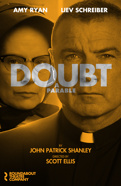

Both modes are likely to be on display in Kazan’s latest role on Broadway in Roundabout Theatre Company’s revival of Doubt: A Parable, John Patrick Shanley’s acclaimed 2004 study in uncertainty. Set in a parochial school in the Bronx in 1964, the play centers on Father Flynn (Liev Schreiber), a likable priest who takes an unusually keen interest in one of the pupils, and is thrown into a battle of wills with the strictly by-the-book Sister Aloysius (Amy Ryan). Kazan plays the impressionable Sister James.

With the production in previews—and featuring a different cast than was originally envisioned—Kazan spoke to Broadway.com about navigating cast changes, the inherent mysteriousness of acting (including the legacy of her grandfather, the director Elia Kazan) and the child's-eye perspective of the play.

Zoe, you’re a writer from a family of writers. What have you learned about John Patrick Shanley's writing while working on Doubt?

For me, the great horror is when you are in rehearsal and you realize that a play is not endlessly generative for you. I just hate being bored. This is the opposite of that. I'm going to be learning things about this until our final performance.

One thing that John Patrick Shanley said was, “I'm really just writing about my experience of things that I saw when I was a child.” That really reframed the play for me. I just love this idea of John as this child, absorbing all of this detail and then, in his middle age, writing it down. There's a kind of central mystery in the play, which is the mystery of childhood, which is that adults are unknowable. Then you grow up and you realize that that's just the mystery of life. People are unknowable to each other.

Only a couple of years ago, you played a real-life journalist taking down a powerful man. This play is also about a powerful man being taken down, in a way. Have you thought about the connection there?

For me, She Said is really about proof. It's really about the journalistic process of how to pin down something that had been floating in the air for a really long time. This is a situation where there is no proof. We don't need to litigate whether or not this one imaginary character did this one thing. People can be cruel to each other in terrifying ways that have terrifying impact on other people without them being terrible people. That's really interesting to me. I don’t mean it to sound like I'm leaving out the idea that Father Flynn could have done this terrible thing. It's just so much more interesting to me to think of this as a play without a villain—that these are all just people trying their best.

If you assume that all four of the characters in this play are doing their best to protect these children, there's something very interesting at the center of the play that is a bigger thing about change in society. The way that we think about certainty and the way that we think about stretching yourself to look at another perspective, and what are the limits of empathy. What's good about those limits? What's not so good about those limits?

"There are a thousand ways to play each of these scenes and we'll figure out the best version, to the best of our ability with who we have." –Zoe Kazan

As a mother of two, does the play feel differently to you than it might have several years ago?

No, this subject matter has always seemed really potent to me. I didn't need to become a parent in order to feel that. However, there is so much in this that the experience of becoming a parent has opened my heart and my understanding of humanity. I feel like my relationship to my work is really different, my relationship to myself is different, my relationship to my understanding of humanity is different. That is the thing that I feel the most excited about.

You've collaborated with your partner [Paul Dano] on projects in the past. Have you two discussed the play?

I never see him! I leave for work after we've gotten our daughter off to school and he immediately goes to work writing. The mornings are all like, "Did you pack a snack?" And then we don't see each other all day.

Frankly, this is a huge lift for my family to make it possible for me to do this. I don't know the next time that I'm going to be able to do this or want to do this. Even though this is a very thorny play with some very hard material, I truly come to the stage with joy every night to get to do this work. I don't take one minute of it for granted, including the really hard stuff, like losing our lead the day that our play is supposed to start previews.

Right. Tyne Daly was hospitalized on the first day of previews and departed the production. Understudy Isabel Keating stepped in for a week. Now Amy Ryan has taken over the role. I feel destabilized switching computers at work. What's it been like for you to have three different Sister Aloysiuses?

In some ways it's a beautiful learning experience and acting exercise. I'm so grateful to Isabel and to Amy for being so brave. This company has found ways to support each other so we can keep telling the story every night and keep learning from these previews, even in the midst of unexpected and difficult circumstances. I feel lucky. And I’m sending so much love to Tyne, always.

It's been very different with all three of them, which is so interesting. I've been sort of astonished and curious about the different colors that each of these actors have brought out in the text and in me. I’ve felt very strongly that we are coming at the text almost in the way that you would come at a classical piece of text or an extant piece of text—the way that you might revisit a Chekhov play or something. Not in terms of the acting style or the tone, but in terms of the flexibility of the text, leaving it open for interpretation rather than feeling like we're re-mounting something. There are a thousand ways to play each of these scenes and we'll figure out the best version, to the best of our ability with who we have.

There’s a recent-ish book about method acting—your grandfather, the director Elia Kazan, of course features in it. The book notes how Elia really wanted his actors to connect the dots between their offstage selves and their characters. Is that something you’ve thought about in relation to the play?

My grandpa wrote this actor's vow that sometimes gets printed up and people put it up in their dressing rooms. There’s a line in it that's like, "I am enough." All we have, as actors, is ourselves. That's what makes it possible for Isabel Keating's Sister Aloysius to be so different from Tyne Daly's, to be so different from Amy Ryan's. People carry their life experience and their character and their makeup and something ineffable on their face and inside of themselves. Deeply inside of themselves.

Bringing yourself to a role with openness and curiosity allows you to give something to the character that then the character gives back to you. It sort of starts this feedback loop.

What were your thoughts on the book more broadly?

It was really relieving to me to read it. The greatest minds of the twentieth century, who thought primarily and very hard about acting, basically had no consensus on how to talk and write and think about acting. And most of them at some point in their lives thought, actually, I have no idea what I'm talking about.

Basically, I came out the other side being like, oh, acting is witchcraft. You get up there, you say certain words in certain orders like a spell. You enact the ritual in a specific way, and then at the end of the day, you walk away from that and something has changed. I felt incredible freedom after reading that book. However I do it is the way that it's going to work for me.