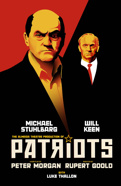

How Will Keen Brings Vladimir Putin to Chilling Life in Broadway's Patriots

(Photos by Luis Ferrá for Broadway.com)

In 2015, the British Medical Journal published a study on a phenomenon that the researchers observed among highly ranked Russian political figures and officials, including President Vladimir Putin: a distinctive gait characterized by a reduced swinging of the right arm. The researchers attributed the movement to K.G.B. weapons training, which enables the trainee to swiftly access a firearm. The researchers called it “gunslinger’s gait.”

That very specific way of walking, with its eerie combination of swagger and stillness, is just one of the physical trademarks that the British actor Will Keen mastered in order to play Vladimir Putin on stage. “It’s a strangely empowering kind of walk,” he said.

A tense political thriller written by The Crown creator Peter Morgan and directed by Rupert Goold, Patriots charts the rise of the man who was, seemingly overnight, handed the reins of power to Russia. It also tells the story of billionaire oligarch-turned-Kremlin insider Boris Berezovsky, played by Michael Stuhlbarg on Broadway, who orchestrates Putin’s rise, only to seriously regret it. The play premiered at the Almeida Theatre in London before a run on the West End in 2023. Keen won an Olivier Award for his performance.

Keen channels the Russian president with chilling exactitude—not just the gait, but the pinched vocal quality, the muscles around the eyes, the morphology of the mouth and an overall quietude that unnervingly suggests the pent-up explosive potential of a grenade. “There's sort of an almost imperceptible chuckle going on,” said Keen, “which I find gives this kind of ironic perspective. It throws the head slightly further back. It’s been very fruitful examining, physically, what stillness does, and what a mask to the face does, in creating a sort of inner tension and an explosive interior place.”

In the show’s most darkly enthralling moment, Putin regards himself in the mirror—trying on, as an actor might, the appropriate posture and bearing for his new position of power. For the audience, there’s the added metatextual thrill of Keen transforming before our eyes into Putin’s familiar physicality.

In Keen’s description, it sounds an awful lot like a possession. “What I find interesting about approaching a character from a physical perspective is that it takes the brain away,” he said. “It lets the instinct do its work and it lets the physiognomy of the body just take you to places that you wouldn't normally go in everyday life. That's a fascinating and sort of liberating experience—without wanting to judge what it is or what it means. It just takes me somewhere else.”

To prepare for the role, on top of studying hours of footage of Putin, Keen read First Person, a book of authorized in-depth interviews with the Russian leader. “I found them very revealing. They are palpably what he wants the world to think of him and what he thinks of himself—what his own version of his own truth is. I felt very strongly in that book that the sense of betrayal and loyalty is central to his identity.

"If one is spending a lot of time trying to imagine being... within that person's mind, of course you feel a curious kind of affinity."

–Will Keen

“I found it useful thinking in terms of the medieval idea of the king as the body politic—that he's the nation in some way. If there's a slight to the nation, it's a slight to him, and if there's a slight to him, it's a slight to the nation. That was my way in as an actor.”

In recent years, Keen has found himself portraying a succession of wicked, corrupt and otherwise morally dubious roles, including the murderous Father MacPhail in the His Dark Materials television series. (Keen’s daughter, Dafne, plays that show’s heroine Lyra.) Goold has said Keen is “brilliant at playing psychopaths.”

“That's very kind of him,” said Keen. “I do enjoy exploring outsiders and obsessives, so maybe there's something in that.” It’s also possible that Keen—as a bald man—has been subject to a kind of follicular type-casting. “When I was in my thirties, I played a lot of priests and lawyers. And then when I was in my forties, I started playing psychopaths. I think that may be to do with simply the way my hair grows.”

Keen was last on stage in New York in 2011 playing another power-lusting autocrat, the title character in Cheek by Jowl’s Macbeth at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. (The New York Times noted Keen’s “chilly ferocity” in the role.) The Scottish king and the Russian president have a certain unyieldingness in common. “I have found myself, in both parts, shoring myself up in a kind of fortress mind,” said Keen.

One big difference is that Macbeth doesn’t typically feature in the daily news cycle.

The Almeida Theatre programmed Patriots immediately after Russia invaded Ukraine in February, 2022. Two years later, the play continues to feel all too timely: the show’s Broadway run was announced just a few weeks before the death of Russian opposition activist and political prisoner Alexei Navalny. “In the Scottish play, you see the full story and you get the resolution of him coming to a sticky end,” said Keen. “What's curious about this is that actually he just gets stronger and stronger and stronger throughout. It's a different shape to it.”

The play’s unmistakable connection to current world events—the sense that we are living the play’s epilogue—results in a heightened attention in the theater. “There is a very, very still and quiet feeling of listening. Every day something happens and slightly shifts the end of the story in the audience's imagination—without having to change anything formally in the play. It does feel like an evolving dialogue.”

Patriots brings out the Shakespearean sweep of Putin’s rise. On the other hand, it humanizes the man beyond the headlines. Born into poverty, raised in a cramped communal apartment, forced to supplement his income as a taxi driver, a pawn in someone else’s scheme… Audience members might be discomfited to find themselves feeling sympathy for the devil.

Keen himself has developed a complex empathy for Putin—one that he articulates carefully. “If one is spending a lot of time trying to imagine being within that person's body, within that person's mind, of course you feel a curious kind of affinity. That's nothing to do with an affection. It’s just a sort of connection.”

Putin doesn't occupy Keen's thoughts after a show—“Once you've done it, you’ve washed it away," he said—but the day leading up to a performance is a different matter. The character, with all the darkness it entails, gradually descends on him like a shroud throughout the day. By showtime, he is engulfed. “You are kind of carrying it around in your head all day; you're slowly pulling it all back in," he said. "I'm not too troubled by it coming off stage and going home at night. It's more complicated during the day."