Boulevard of Broken Dreams: The Long Road to a Sunset Boulevard Musical

(Film still: Paramount Pictures)

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Sunset Boulevard had its world premiere in London in 1993, opening on Broadway the following year. The backstage drama behind those premieres has been well documented, but the journey from classic film to stage musical was even longer and more winding than most realize.

With a new production now on Broadway, it’s the perfect time to trace a half-century's worth of attempts to make a Sunset Boulevard musical, and explore how a succession of artists—aging movie star, tenacious producer-director, master composer and more—were ensnared and seduced by the dream of it, only to wind up defeated and disillusioned.

AS IF WE NEVER SAID GOODBYE

The dream of a Sunset Boulevard musical began with Gloria Swanson.

In the silent-movie era, Swanson was Hollywood royalty—perhaps the greatest star of them all. The moviegoing public knew her simply as “Gloria.” At her superstar peak—as the director Billy Wilder was fond of recounting—she was conveyed in a sedan chair from her dressing room to the soundstage by four footmen while every member of the cast and crew bowed to the ground.

In 1950, Swanson made a triumphant return to the silver screen in Paramount Pictures’ Sunset Boulevard. She played Norma Desmond, a reclusive, delusional silent-film star who dominates and murders Joe Gillis, a young screenwriter, while vainly dreaming of a comeback. The movie opens with Joe's corpse floating in a swimming pool.

The film was Billy Wilder and screenwriter Charles Brackett’s poison valentine to the industry. (Louis B. Mayer slammed the film for profaning the business. Wilder’s response to the head of M-G-M: “Go sh*t in your hat.”) One critic would describe the film’s central theme as the “mad attempt to sustain an impossible illusion.”

Swanson was engrossed in the making of Sunset Boulevard. She sang to herself every morning on the way to work, collaborated with costume designer Edith Head on her outfits and provided personal props from her own life for the mise en scène. The whole process was, she recognized, a very revealing one for her: “something akin to analysis.” For her, the glorious return was real—the whole thing felt, she said, “as if [I’d] never been away.” She dreaded the end of filming.

Sunset Boulevard premiered in New York on August 10, 1950. The critics lavished the film and Swanson’s performance with praise. “Parts like this come once in a lifetime,” said the Hollywood Reporter. “[I]t is inconceivable that anyone else might have been considered for the role,” wrote Thomas M. Pryor in the New York Times. “Even in those few scenes when she is not on screen her presence is felt like the heavy scent of tuberoses which hangs over the gloomy, musty splendor of her memento-cluttered mansion in Beverly Hills.”

No wonder she didn’t want the spell to be broken.

A few years later, Swanson was approached by two young songwriters, Richard Stapley and Dickson Hughes, about starring in a potential stage-musical project. But Swanson had been burned by her most recent Broadway role, in 1951’s Nina. She told them she would never do another Broadway show. “Well,” she added, “not unless somebody writes a musical adaptation of Sunset Boulevard.”

Stapley and Hughes got to work the next day. When they finished a song, they immediately called up Swanson to play it to her over the phone. She loved it. Work on Sunset Boulevard: The Musical got underway. In a letter to her fans in February 1955, Swanson wrote that work was progressing on the show. “I can barely contain myself. Another wish has been granted me. And I am truly blessed.”1

Over the next few years, Swanson spent $20,000 of her own money on the project—equivalent to around $200,000 today—wooing producers and performers, recording demos of the songs and dialogue to play for potential investors. Stapley and Hughes proceeded to throw sunshine onto the story’s gothic gloom. At Swanson’s request, Norma was rewritten to be a more sympathetic character. Joe Gillis ends up with the bright-eyed script-reader Betty Schaefer, with Norma’s blessing. There is no swimming-pool corpse.

Swanson came up with the title herself, encapsulating the lighter, frothier tone of the adaptation: Boulevard!

Her song demos, preserved at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, have surfaced in recent years, including in the 2021 documentary Boulevard! A Hollywood Story (one number is currently on YouTube). The recordings reveal that Swanson largely spoke-sang the part of Norma like a female Rex Harrison, occasionally managing to caw something that approximated a melody. In 1957, Swanson proudly debuted a number from the show on The Steve Allen Show.

"They’ll never turn ‘Sunset Boulevard’ into a musical" –”Swanson on Sunset”

Only two years later, Paramount reneged on whatever agreement they’d had with Swanson to develop the project. “It would be damaging for the property to be offered to the entertainment public in another form such as a stage musical,” their letter went. Swanson tried desperately to “salvage this beautiful project,” to no avail. Her collaboration with Stapley and Hughes—who were romantic partners—fell apart after Swanson developed amorous feelings for Stapley.

Many years later, Hughes would make his own musical about his Boulevard! experience. In Swanson on Sunset, a character remarks, “They’ll never turn Sunset Boulevard into a musical.”

Swanson's musical was dead in the water. But she wasn't quite ready to let go. “As soon as she knew there was a chance of doing Norma Desmond every night,” said Stapley, “she became more and more Norma Desmond, and less and less Gloria Swanson.”2

THE QUEEN MEETS THE PRINCE

In the early 1960s, years after Paramount officially nixed the project, Gloria Swanson invited the Broadway producing duo Harold Prince and Robert E. Griffith to a suite in the Sulgrave Hotel on Park Avenue. “I never go out on auditions,” Prince later said, “but because of her stature I made an exception.” In the bedroom of the suite, with Dickson Hughes on piano, the actress put on a presentation that lasted close to four hours. Prince would also recall how Swanson thrust a sheaf of storyboards at him—evidently, she’d labored over them herself—replete with costume designs, scene breakdowns and dialogue.

In fact, Prince had caught Swanson's Boulevard! performance on The Steve Allen Show in 1957. But while he endured Swanson's presentation mostly out of politeness, he was already seriously contemplating the possibility of a Sunset Boulevard musical. He had optioned the rights in 1961.3

With Prince backing them, Stephen Sondheim and Burt Shevelove got to work on adapting Sunset Boulevard after their success with A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. The pair got as far as writing an outline and the first scene—Sondheim had also composed some “misterioso” music—when Sondheim bumped into Billy Wilder at a cocktail party. “But you can’t write a musical of Sunset Boulevard,” Wilder told Sondheim. “It has to be an opera. After all, it’s about a dethroned queen.”

Sondheim realized Wilder was right. “It’s such a flamboyant subject you can’t do it as a musical. The minute they would talk you would scream with laughter because they’re such bigger than life figures, and you can’t go swanning around that stage the way the lady would have to, and then sit down and have camp dialogue.”

(Swanson did eventually prove a source of inspiration for a Prince-Sondheim musical project. After Company opened in 1970, Prince found himself paging through The Best Remaining Seats, a photographic history of old movie palaces, coming across a photograph of Swanson standing among the rubble of what had been New York’s Roxy Theatre. The image would inspire Follies.)4

Prince remained interested in the idea, even as he transitioned into directing in the ‘70s. In 1980, he put Sweeney Todd writer Hugh Wheeler to work on a book for the show. He had also come up with a concept. In his update of the story, Angela Lansbury would play a Doris Day-style 1950s musical comedienne cast aside by Hollywood progress. “[I]t seems to me the most perfect subject for a musical comedy: a musical comedy star desperately trying to make a comeback,” Lansbury told the New York Times.5

Prince still hoped Sondheim would come around to the idea. In late 1980, Prince proposed pausing work on Merrily We Roll Along in order to meet Paramount's March 1, 1982 deadline and retain the rights. Sondheim still wasn’t interested.

Prince was in discussions with other composers. A Sunset Boulevard collaboration between Prince and John Kander and Fred Ebb similarly fell apart. “I’ve been walking around for a year now with such uneasy feelings regarding the Sunset Boulevard debacle,” Prince wrote them in a 1981 letter. He suggests getting together to clear the air; things had ended badly.

But Prince had already successfully planted the idea in the mind of another composer.

DANGEROUS LIAISONS

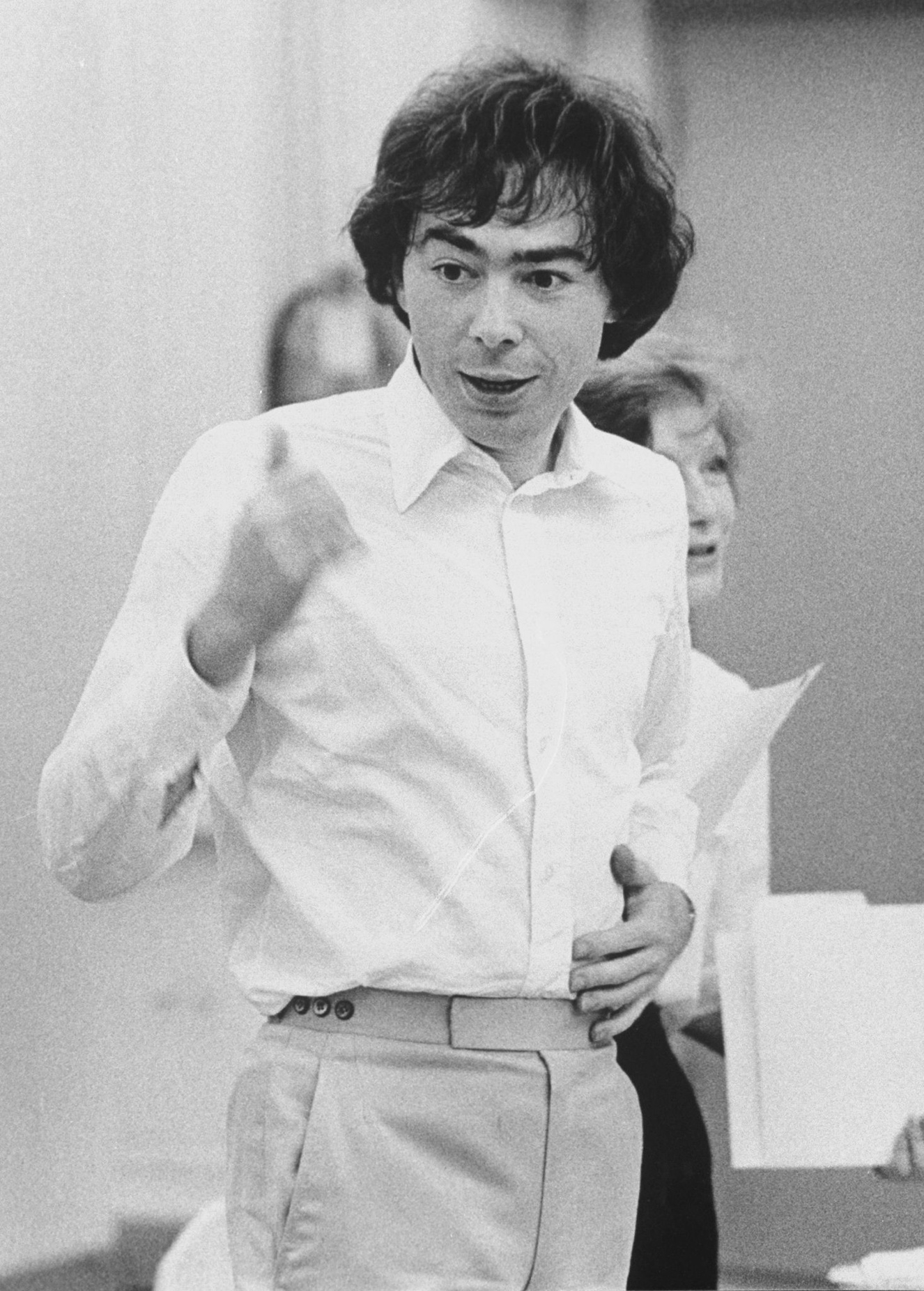

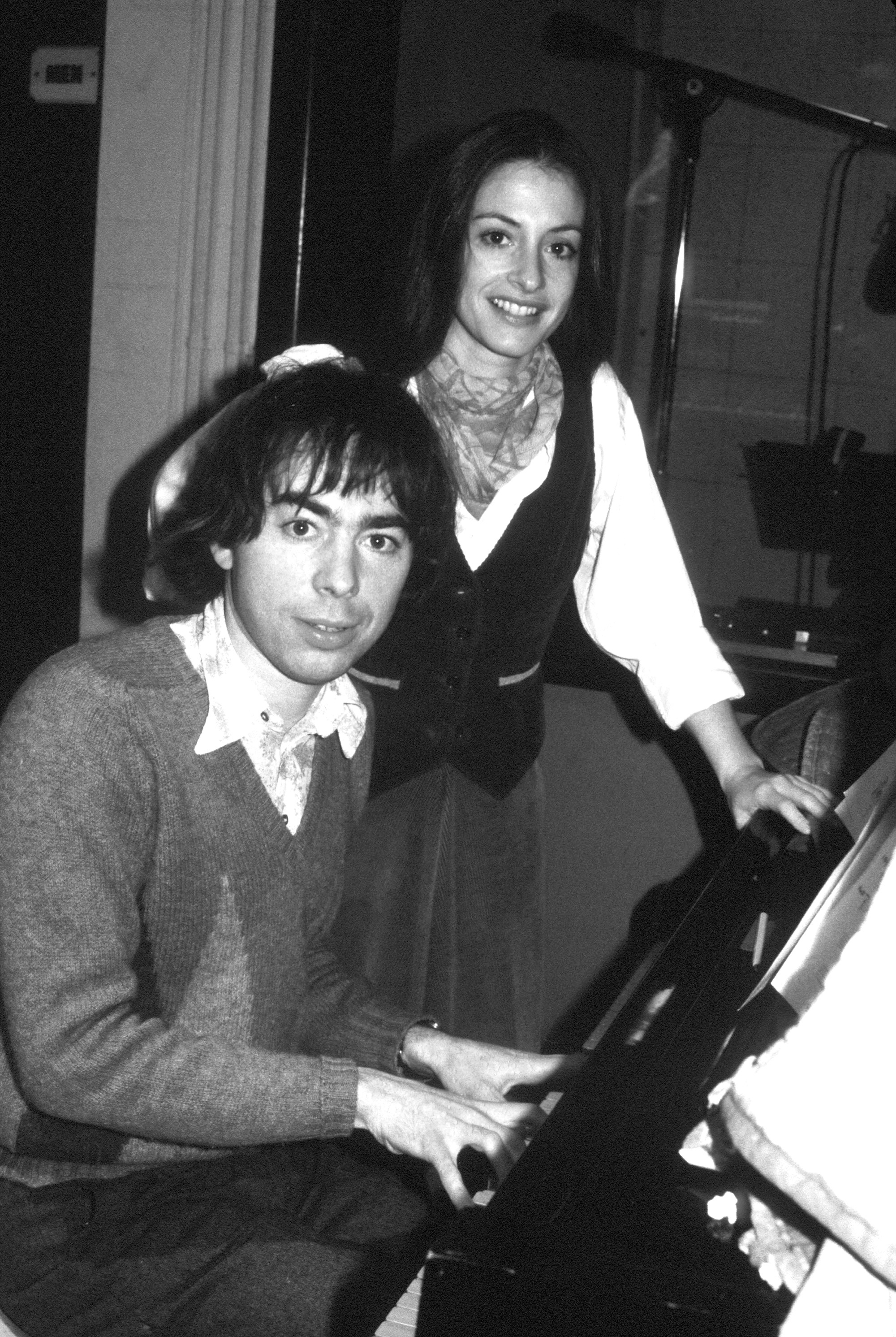

Back in 1979, Harold Prince arranged a screening of Sunset Boulevard for the most quasi-operatic of musical theater composers, Andrew Lloyd Webber. “I immediately saw why,” said Lloyd Webber. “The story of Norma Desmond, the silent movie star whom the talkies passed by and her obsession with a younger man, struck me as a brilliant subject.”6

Lloyd Webber started developing song ideas with Don Black. Black was the lyricist behind the movie theme-crossover hits "Born Free," "To Sir, with Love," "Diamonds Are Forever" and "Ben"; the duo had just collaborated on the song cycle Tell Me On a Sunday. Lloyd Webber admired Black's sensitivity writing for female characters; Black also had a knack for precisely tailoring lyrics to the composer's set-in-stone melodies.

One of the new songs Lloyd Webber and Black came up with was a theme for Norma. Lloyd Webber had actually composed the tune for a Puccini musical that never got off the ground—it had a sweeping, intentionally Pucciniesque melody and built to a soaring climax. But it wouldn’t make it into Sunset Boulevard. Instead, the melody went back into Lloyd Webber’s proverbial "tune bank." Eventually, it would re-emerge as “Memory” in Cats.

Meeting Prince and Hugh Wheeler in New York, Lloyd Webber was dismayed to discover that, as he put it in his memoir, “Hal had one of his concepts.” The composer didn’t see the point of Prince's Doris Day-inspired update of the story. But he was hooked on the essential idea of a Sunset Boulevard musical, and after Prince finally let the rights lapse in 1982, Lloyd Webber quietly snapped them up.

Lloyd Webber proceeded to have a very busy decade. After Tell Me On a Sunday came Cats, Song and Dance, Starlight Express, The Phantom of the Opera and Aspects of Love.

In the midst of all that was the project that might have been. In 1985, Lloyd Webber met with Roy Disney Jr. (nephew of Walt) and Jeffrey Katzenberg of the Walt Disney Company. They were interested in having Lloyd Webber compose the songs for Disney's next animated feature; they'd brought along a selection of storyboards featuring beautifully drawn mermaids. Lloyd Webber, who was preoccupied with thoughts of phantoms and chandeliers at the time, suspected his musical sensibility would probably be too dark for Disney’s mermaid cartoon. But after a few months, he gave it a shot, writing a lush, romantic tune with a yearning melody that rose and fell like ocean waves. By then, though, Disney had moved on. (“Shame, really,” Lloyd Webber would say later, “’cause if I’d done The Little Mermaid, maybe I’d have done the big cats in The Lion King.”) The song would not go to waste.

After Aspects of Love, Lloyd Webber was ready to properly embark on the making of Sunset Boulevard. The original plan was to collaborate on the project with Howard Ashman, who had landed the Disney job, but his deteriorating health after an AIDS diagnosis in 1988 ended those plans. Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita collaborator Tim Rice was also involved in early discussions on the project. Rice passed, reportedly deeming the characters of Sunset Boulevard too unsympathetic.

Knowing Lloyd Webber was in need of a lyricist, Shubert Organization chairman Gerald Schoenfeld suggested he contact Amy Powers, a former real estate lawyer making the pivot to songwriting. Powers had completed the BMI Lehman Engel Musical Theatre Workshop, where her final-year project was a musical adaptation of Dangerous Liaisons.

One day, Powers received a phone call. A very proper British voice came on the line: “This is Andrew Lloyd Webber. I’d like you to come meet me next week at my house in the south of France. I want to talk about writing a show with you.”

Powers was in shock. “It’s like saying to somebody, ‘We like how you look on the bunny slope. So guess what—the Olympics are next week!’” She met Lloyd Webber at his Cap Ferrat property the following week and got to work. The collaboration was not what she had expected. There was none of the back and forth and exchange of ideas she had enjoyed at BMI. Instead, she was largely tasked with setting lyrics to Lloyd Webber’s ready-made tunes.

Some of these were pulled out of the tune bank. For the pivotal scene in which Norma returns to Paramount, Lloyd Webber recycled a piece of music from Cricket, his last complete collaboration with Tim Rice, a mini-musical commissioned for Queen Elizabeth II’s 60th birthday celebration. (Queen Elizabeth II’s son Prince Edward worked for Lloyd Webber’s company, Really Useful Group.) The show culminated in the lovers' duet:

If lazy games of summer

Were all that really mattered

I’d chase that ball until they all stopped cheering.

As I’ve just discovered

The running gets you nowhere

A lot can change in one hot afternoon.

The song, minus the cricket metaphors, eventually became Norma’s would-be-triumphant “As If We Never Said Goodbye.”

For Sunset Boulevard's title number, Lloyd Webber dug out a piece of music from his score for the film Gumshoe—composed back around the time of Jesus Christ Superstar—reworked with a churning, restless 5/8 time signature. And for the scene in which Norma recounts her glory days as a silent film actress, Lloyd Webber’s mermaid tune resurfaced. Elaine Paige sang the resulting number, “One Small Glance" (eventually "With One Look"), at Lloyd Webber's wedding to his third wife, Madeleine Gurdon, in early 1991.

Six months into the collaboration, which by now had relocated to London, Lloyd Webber invited Don Black to also work on the project. It didn’t occur to Powers that Lloyd Webber was potentially lining up her replacement.

By the summer of 1991, Act One of Sunset Boulevard was ready to be unveiled at Sydmonton, Lloyd Webber's country estate, where the composer put on an annual arts festival primarily to premiere his new work. The performance kicked off at noon. Lloyd Webber looked at his watch, which said 11:45. “I think I have time for one more tantrum,” he said. Norma was played by Ria Jones, who had already played Eva Perón in Evita and Grizabella in Cats in the West End. Jones was only 24—there was no thought that she would play the role in a Broadway or West End production.

The first work-in-progress presentation of Sunset Boulevard was less than a resounding success. Elaine Paige leaned over to Black during “One Small Glance” to say, “You’ve got to do something about those lyrics.”

After the showing, Powers went home to New York, expecting to resume work on the musical in a couple of weeks. But on September 20, Powers picked up a copy of the New York Times, where she encountered Alex Witchel’s theater column. Witchel reported that Powers’ lyrics had met with a “lukewarm response” and were the “dark spot” of an otherwise successful presentation. She announced that Lloyd Webber had decided to let Powers go.

Ultimately, Powers would receive an “additional lyrics” credit on four key songs in Sunset Boulevard: "With One Look," "The Greatest Star of All," "Sunset Boulevard" and "As If We Never Said Goodbye." She received an undisclosed sum from Really Useful Group. "You'd need a microscope to see it." She never heard from Lloyd Webber again.

Work resumed in Cap Ferrat in the fall without Powers, but with the addition of Christopher Hampton.7 Hampton was the writer behind Dangerous Liaisons, a Broadway hit and then a film starring Glenn Close as a scheming aristocrat.

Lloyd Webber, Black and Hampton met in the mornings. Then “Chris and I would go off to write lyrics or a scene in the afternoon,” said Black, “while Andrew walked around his gardens or checked his wine cellar.” The plan was to present the entire show at Sydmonton in 1992. Before then, they needed a Norma.

A DETHRONED QUEEN

In August 1992, Patti LuPone was in Los Angeles, starring in the fourth season of the dreary ABC drama Life Goes On. It had been five years since her last Broadway role in Anything Goes. "I missed singing," she wrote in her memoir. "I missed being onstage."

Then David Caddick, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s longtime music director, called with an invitation: Would she like to sing the lead role in the composer’s new musical, Sunset Boulevard, in a workshop presentation at Sydmonton Festival?

LuPone—who had won her first Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical for playing Eva Perón in Lloyd Webber's Evita—didn't hesitate. "Are you kidding?" she thought.

With Kevin Anderson, who would play Joe Gillis, LuPone rehearsed for three weeks in Los Angeles, drilling the songs in her trailer. She had a hunch the workshop presentation would actually be an audition for a full-fledged production.

The September presentation was a success. “When she sang the first solo, ‘With One Look,’ the acoustic effect in the tiny building was electrifying,” read one report. Meryl Streep sat in the front row and was teary-eyed by the show’s end.

Lloyd Webber pulled LuPone aside at dinner that night. “Name your price,” he said.

“Kevin Anderson,” she replied. Later, she wished she’d said, “Call my agent.”

When he heard the news, Sondheim sent LuPone an amusing gift. He had obtained an audio recording of Gloria Swanson singing from Boulevard! on The Steve Allen Show. LuPone had a good laugh at poor old Gloria.

But soon her own troubles began.

Rumors were flying that Streep was up for the role of Norma; one gossip columnist went so far as to confirm Streep had been offered the role. (LuPone suspected that the rumors were a publicity tactic.) Barbra Streisand, at Lloyd Webber’s invitation, recorded “With One Look” and “As If We Never Said Goodbye.” LuPone felt she’d had her thunder stolen, just as she had when Streisand recorded “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” before the opening of Evita.

Most troubling of all, Lloyd Webber hatched a plan to open Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles while the West End production was still running. There would be two Normas. In May 1993, just as she was ready to fly to London to commence rehearsals, LuPone learned that the other Norma would be Glenn Close. It took three days of negotiations to convince LuPone to get on the plane to London. As she finally boarded the plane, she took a call asking if she was interested in the role of Fosca in Sondheim’s new musical, Passion. She cursed her luck.

Lupone had issued a list of demands for Lloyd Webber and the team. Chief among them was a kind of restraining order against Close, expressly forbidding her from attending the London premiere or “being in the vicinity while I was rehearsing the part.”

Lloyd Webber—who had already acquired, gutted and refurbished London’s Adelphi Theatre to the tune of £1.5 million to present the world premiere of the production—had a sinking feeling. “Everybody was walking on eggshells,” he recalled in a conversation quoted in Singular Sensation. “I was frankly utterly shaken. None of the work we might normally have done in rehearsals got done because we were afraid we might upset Patti.”

The composer had approached Harold Prince to direct Sunset Boulevard, but Prince was otherwise engaged with bringing Kander and Ebb’s Kiss of the Spider Woman to Broadway—the director’s first project with the duo since their aborted Sunset Boulevard. Cats director Trevor Nunn was brought on instead.

As opening night approached, even the palatially extravagant set by John Napier began mutinying. At random moments, Norma’s living room would lurch as much as four feet downstage at a time, with the actors still on it. The equipment issues delayed opening night by two weeks, causing severe headaches at the box office and continuing to plague the production throughout the run.

Billy Wilder, aged 87, was there on opening night on July 12, 1993. “The best thing they did was leave the script alone,” he said. He enthused about LuPone (“She’s a star from the moment she walks on the stage”) but had little to say about Kevin Anderson (“I just wish he’d change his hair style”).

The harshest reviews were from the American critics whom Lloyd Webber had specially invited. LuPone was described as “miscast and unmoving” and a “distinctly negative hurdle”. The Philadelphia Inquirer reckoned “Patti LuPone doesn’t seem crazy enough.” On the other hand, when Sunset Boulevard opened in Los Angeles in December, the critics raved about Glenn Close.

In London, LuPone soldiered on to standing ovations at the Adelphi, until February 16, 1994. LuPone was in her dressing room when she received a call from her agent in New York. Gossip columnist Liz Smith had taken the liberty of making the announcement in the New York Daily News: “It isn’t even a bet; it’s a fact. Although the Andrew Lloyd Webber company won’t confirm or deny, Glenn Close will begin rehearsals as Norma Desmond in New York on August 1.”

“I got fired in Liz Smith’s column,” LuPone wrote. “From the outside, I’m sure it sounded like all hell had broken loose in my dressing room, which in fact it had. I was hysterical … I took batting practice in my dressing room with a floor lamp. I swung at everything in sight—mirrors, wig stands, makeup, wardrobe, furniture, everything. Then I heaved the lamp out the second-floor window.”

In her last weeks of playing the role, the role of Norma felt more personal to LuPone. “There’s a scene in the show where Norma is looking at her old movies, and she has a line about being discarded. I owned that line now.” Her Norma was better—and more crazed—than ever. Lloyd Webber wrote LuPone a letter saying he was as upset as she was. “Go sh*t in your hat,” thought LuPone.

LuPone finished the London run on March 12, 1994. Her final curtain call went on for 20 minutes.

The depression that followed wasn't helped by the fact that her four-year-old son Joshua went around singing the score, and for some reason delighted in play-acting the moment of her firing. “Fire!” he would shout, pointing at her.

“The open wounds closed, but even so, those scars never go away,” said LuPone. “I know I’m the same person I was before I went into the Sunset Boulevard debacle, and I’m the same person who came out of it, just wounded, bruised, beat up, and bloodied. So actually maybe I’m not the same person. Maybe I’m a little bit stronger for having survived it.”

LuPone took legal action against Lloyd Webber for breach of contact. You would not have needed a microscope to see her settlement payout of more than $1 million.

FADE TO BLACK

Sunset Boulevard opened on Broadway on November 17, 1994, starring Glenn Close as Norma Desmond. The show received 11 Tony nominations the following year, winning for Best Musical and Best Actress in a Musical for Close.

The show was also a financial disaster, its weekly running costs greatly exceeding initial estimates. The national tour was also operating at a considerable loss. The situation wasn’t helped by a second costly breach-of-contract lawsuit courtesy of Faye Dunaway. The actress had been announced to replace Close in Los Angeles, but Lloyd Webber deemed her voice substandard and opted to close the production prematurely instead. The payout cost another reported $1 million.

The production closed on March 22, 1997, after 977 performances. The national tour similarly ground to a halt, along with productions in London, Canada and Australia. Former New York Times critic Frank Rich pronounced the show a “hit-flop,” calculating the losses at more than $20 million. Sunset Boulevard set a new record for the most money lost by a Broadway show (or theatrical production of any kind) ever in the U.S.

Lloyd Webber felt defeated by the whole experience. “I was incredibly hurt by some of the things Patti had said, and by the way I was perceived,” he said. “I very nearly put my whole company up for sale. The joy had gone out of it. I never wanted to go near a theater again.”

As we know, Lloyd Webber would return to the theater and to Broadway eventually. But Sunset Boulevard did signal the bitter end of the composer’s astonishingly successful reign in New York—an epic tombstone for the era of the big, bold (and British) megamusical. You might say it's the musicals that got small.

Famously, LuPone put a portion of her payout money from Really Useful Group towards installing a luxurious pool in her 85-acre property in Kent, Connecticut, naming it the Andrew Lloyd Webber Memorial Swimming Pool.

Asked about her own payout, Powers eyed her own swimming pool. “That tile over there, the one that needs to be replaced—I would say that is the Andrew Lloyd Webber Memorial Tile.”

As for Gloria Swanson, until her death by a heart ailment in 1983, she would regale guests in her Upper East Side home with recordings of Boulevard! According to her old collaborator Dickson Hughes, “It never died for her."

(Photo: Marc Brenner)

SOURCES

Black, Don. The Sanest Guy in the Room. 2023.

Boulevard! A Hollywood Story. Directed by Jeffrey Schwarz, 2021.

Perry, George. Sunset Boulevard: From Movie to Musical. 1993.

Powers, Amy. Interview conducted by author.

Prince, Harold. Sense of Occasion. 2020.

Rice, Tim. "The Lost Cricket Musical." Get Onto My Cloud, Broadway Podcast Network. 2021

Riedel, Michael. Singular Sensation: The Triumph of Broadway. 2020.

Secrest, Meryl. Stephen Sondheim: A Life. 1998.

Sikov, Ed. On Sunset Boulevard: The Life and Times of Billy Wilder. 1998.

Stagg, Sam. Close-Up on Sunset Boulevard: Billy Wilder, Norma Desmond, and the Dark Hollywood Dream. 2002.

Swanson, Gloria. Swanson on Swanson: An Autobiography. 1980.

The Harold Prince Papers. New York Public Library, Billy Rose Theatre Division.

Welsch, Tricia. Gloria Swanson: Ready for Her Close-Up. 2013.

FOOTNOTES

1 At age 13, performing in her school musical in an opera house in San Juan, Gloria decided that being an opera singer “had to be the most exciting thing a woman could hope to be.” ↩︎

2 While the Gloria-Norma comparison might feel a little easy, the same thing occurred to Swanson’s ghostwriter Wayne Lawson while working with her on her memoir Swanson on Swanson in the 1980s: “I began to sense more and more strongly that the doppelgänger in the film was taking over." ↩︎

3 In 1960, Prince met with musical comedienne Jeanette MacDonald about her playing the role of Norma. “In truth, I think she would have done it,” Prince said in 1991, but “she died before we got to write the show.”↩︎

4 The true-to-life casting of Sunset Boulevard also inspired Prince’s approach to casting Follies. ↩︎

5 Asked to comment on the choice of Lansbury, Swanson said, “That’s too soft a face,” before reconsidering. “Well, I don’t know, maybe … if I can do Charlie Chaplin, maybe she can do Norma Desmond.” Lansbury later said that no show could not have lived up to the idea of the show. “We decided that it was such a wonderful announcement in the first place, that we could never top it.” ↩︎

6 Lloyd Webber saw the film in the early 1970s—it even inspired some music—but this seems to be the moment the idea clicked. ↩︎

7 A few years earlier, Hampton had looked into securing the rights for Sunset Boulevard as a potential subject for an opera. He contacted Billy Wilder. “You’re a writer,” said Wilder. “How can you possibly suppose that I retain any rights to these movies?” When Hampton got through to Paramount, he was told no—only to eventually find out, of course, that the rights had been claimed by Lloyd Webber. ↩︎

Related Shows

Articles Trending Now

- Death Becomes Her, Maybe Happy Ending, Oh, Mary! and More Earn Nominations for the 2025 Broadway.com Audience Choice Awards

- Ragtime, Starring Caissie Levy, Joshua Henry and Brandon Uranowitz, Is Coming to Broadway

- Carrie St. Louis, Katie Rose Clarke and Quinn Titcomb to Star as Dolly Parton in World Premiere of Dolly: An Original Musical