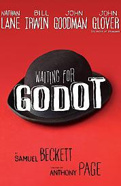

The Wait Is Over for Godot on Broadway

He was referring to Waiting for Godot, the poetically funny, fascinating and perplexing four-man show by then-unknown Irishman Samuel Beckett that went on to mystify, entertain, outrage and touch the entire theatrical community.

“I have been brooding in my bath for the last hour and have come to the conclusion that the success of Waiting for Godot means the end of the theatre as we know it,” the actor Robert Morley famously wrote after Hall gave it its British debut. Morley, of course, was wrong, but his sentiment reflected the vehement arguments that ensued when the play had its English debut in 1955. “Godotmania gripped London,” Hall recalled of the aftermath.

Publicized, satirized and analyzed within an inch of its life, Waiting for Godot became a modern stage milestone, changing contemporary theatrical conventions on its way to being named one of the most influential plays of the last century, despite the fact that almost no one can explain what the play is about and no one, even its author, knows who “Godot” really is.

How did a four-person play about two men waiting around cause such a stir? Much like the play, it’s all open to interpretation.

Rebel, Rebel

Future Nobel Prize winner Samuel Beckett was a personality ahead of his time, a wry brooder and multilingual graduate of Trinity University prone to questioning everything from authority to institutions of higher learning in spite of his own privileged and educated background. Born to a wealthy family in 1906 in a suburb of Dublin, the one-time protégé of James Joyce set on the path of altering dramatic history when he fell into the role of the rebellious twentysomething after college, rejecting pedantry going so far as to present a lecture on a fake subject when asked to speak at his alma mater, writing poetry, sleeping around and reading lots of Marcel Proust and Carl Jung, setting the standard for every graduate student and “artist” for the next century in the process.

Beckett channeled his unrest, which he considered an inborn character flaw, into a number of outlets, publishing critical essays and novels, joining the French Resistance during World War II and, in another bohemian turn, backpacking across Europe, collecting enough nomadic experience and existential fodder to channel into a lifetime of work when he finally calmed down and settled in Paris in the 1940s. Waiting for Godot, his second theatrical work in a portfolio that also includes absurdist staples Krapp’s Last Tape, Happy Days and Endgame, began as what the author called “a relaxation, to get away from the awful prose I was writing at the time.”

Bonjour, Mr. Godot

Godot pronounced GOD-oh, if you’re wondering is, like TV’s Seinfeld some 40 years later, a show essentially about “nothing.”

Set in a no-man’s land populated by rocks, a tree and the moon, vagabonds Estragon and Vladimir wait daily for someone—or something—called Godot. During their wait they twice encounter a rich man, Pozzo, and his slave, ironically named Lucky, and engage in chats about everything from morality to dancing. Outside of their conversations with the passersby, however, “Gogo” and “Didi” as they affectionately call each other anxiously while away the hours by any means possible: sleeping, eating, arguing and playing before being informed by a young boy that “Mr. Godot” will not come “today,” whereby the whole scenario starts up again.

The play made its debut on January 5, 1953, at Theatre de Babylone, a small, experimental space where Parisian actors Pierre Latour Estragon, Lucien Raimbourg Vladimir, Roger Blin Pozzo and Jean Martin Lucky first introduced Godot to theatergoers. Blin, also the director, was a last-minute addition to the cast, replacing the original Pozzo who quit before opening night. French audiences, always more receptive to the avant-garde, applauded the show’s departure from conventional theater though one performance had to be stopped midway due to whistling and booing from a straight-laced crowd after Lucky’s existentialist monologue. Reviewers gave it a warm reception, hinting at the events that would follow when the play made its way to the English stage.

London Calling

In the summer of 1955, while the show still played in Paris, Beckett’s self-written English translation of Godot landed on the desk of Peter Hall, then the director of London’s The Arts Theatre.

“I remember reading it and thinking it was utterly original,” Hall said later. “I won’t say that I said to myself, ‘My God, here’s the play of the mid century,’ because I didn’t. But I’d never read anything like it because it used the theatre as metaphor…waiting was a metaphor for life. I thought it was beautifully written and terribly funny.”

The play had been brought to Hall by British producer Donald Albery, who explained bluntly that no actor or director in London would sign on for the project. Hall jumped at the opportunity; actors, not so much. “None of the actors [I knew] would be in it,” Hall told BBC radio’s John Tulsa years later. “I mean, everybody I asked said no.”

The problem with the piece was that it literally scared actors.

“I agreed to play Estragon before reading the script,” original London cast member Peter Woodthorpe recalled in 1999. “Then I read the script and panicked; not only was Estragon one of the leads, but I couldn’t understand the text. I tried and failed to get out of my contract.”

His mood lifted as the cast including Paul Daneman as Vladimir, Peter Bull as Pozzo and Timothy Bateson as Lucky settled into Beckett’s oddly soothing rhythms. “It was clear that Beckett had ‘directed’ much of the play within the text,” Woodthorpe later observed. “The rhythms and speeds are all on the page.” Still, no one could fathom quite what they were dealing with. When Woodthorpe asked Beckett himself how to discuss the play, the playwright said only, “Tell ’em it’s all symbiosis.”

A Country Road. A Tree.

By opening night, Hall was confident. His cast, however, was frantic. “I’ve never seen actors more frightened than on the first night at the Arts,” remembered Woodthorpe, and rightly so. “We got a terrible reception. I said the line, ‘Nothing happens, nobody comes, nobody goes, it’s awful!’ And a very posh voice from the stalls went, ‘Hear, hear!” After the curtain fell, Hall’s own agent pulled him aside and berated him for “doing a thing like this.”

A flurry of bad reviews, rich with what Hall called “bafflement and derision,” showered down on the production, the best of which called it “an evening of funny obscurity.” The director had to beg the theater owner not to close the play, imploring him to wait for their own personal Godot: the Sunday reviewers. Unlike in the play, Hall’s mythical hero arrived on time, in the form of Sunday Times critic Harold Hobson.

“Dramatic instinct reveals itself in a flow of unexpected, absorbing happenings upon the stage. But a play is something more—it is the flow gradually emerging as some significant image of life. Waiting for Godot, now to be seen at the Arts Theatre in a brilliant production, insists that these truisms shall be restated,” he wrote. Kenneth Tynan followed suit, declaring that “the play forced me to re-examine the rules which had hitherto governed the drama; and having done so, to pronounce them not elastic enough.”

With that, Godot took off. Hall would later explain that it reinvented British theater, making way for Harold Pinter, Joe Orton, Edward Bond and generations of playwrights who would eschew traditionalism. At the end of 1955, one judge of the first Evening Standard Drama Awards threatened to quit if Waiting for Godot won. An “English compromise” was arranged, naming it “The Most Controversial Play of the Year.” Notes Hall, “It is a prize that has never been given since.”

Waiting for Broadway

Godot made its way to Broadway several months later. Directed by Herbert Berghof, the production starred Bert Lahr as Estragon, E.G. Marshall as Vladimir, Alvin Epstein as Lucky and Kurt Kasznar as Pozzo. Billed as a tragicomedy, the show opened at the Golden Theatre on April 19, 1956, to mixed critical reaction and a fair amount of confusion. The actors, direction and production were praised for humor and entertainment value but chided for not conveying the piece’s overall asceticism. Brooks Atkinson’s New York Times review set the tone: “Don’t expect this column to explain Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. It is a mystery wrapped in an enigma…Theatregoers can rail at it, but they cannot ignore it, for Mr. Beckett is a valid writer.”

The American Godot closed after just 60 performances on June 9. An African-American revival comprised of Bert Chamberlain, Geoffrey Holder, Earle Hyman, Rex Ingram and Mantan Moreland later played the Ethel Barrymore for six performances in January 1975, also directed by Berghof.

Godot’s mounting in the United States solidified its longevity in the theater world at large. Productions went up on stages across the globe; universities made the text de rigueur on curriculums for everyone from writers to philosophers; and generations actors have clambered to play the leads, including Peter O’Toole and Donal McCann 1969’s West End revival at The Abbey, John Alderton and Alec McCowen 1987’s National Theatre mounting, Robin Williams and Steve Martin 1988’s Lincoln Center production, Ben Kingsley and Alan Howard 1997 at London’s Old Vic and Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen 2009 Malvern Festival.

Meanwhile, Beckett, who died in 1989, never divulged who Godot was supposed to be God?, nor did he seem to care. “I do not even know if he exists,” the playwright declared in a letter written before the first French production. “And I do not know if they believe he does or doesn’t, those two who are waiting for him.”

Says Anthony Page, the British director of the current Broadway revival, “I worked with Beckett in 1965 and he didn’t want to discuss the interpretation at all. I think often people are much too intellectual about it.”

Didi and Gogo Return

After a long wait, Broadway audiences will again encounter Godot, which opens April 30 at Roundabout Theatre Company’s Studio 54. The play is now in the capable hands of stage stalwarts Nathan Lane Estragon, Bill Irwin Vladimir, John Glover Lucky and John Goodman Pozzo. Irwin, who played Lucky to F. Murray Abraham’s Pozzo in the show’s Lincoln Center production, points out the polarizing effect of the show even on actors.

“I don’t know any actor who isn’t obsessed with this play,” the Tony-winning star told Broadway.com. “Ask any actor about Godot, and they’ll immediately go, ‘Oh, I’d love to do that.’ Or they’ll go, ‘There’s no way I’d ever do that.’ It’s got that kind of weight.”

Lane, stretching far beyond the musical comedy roles that brought him Tonys for The Producers and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, admits to his own longstanding interest in the piece. “I did a scene from it in high school, in the school cafeteria. Somehow I thought this was a swell idea—I believe I was beaten severely afterwards. But it’s exciting, funny, frustrating, emotional—and a challenge.”

“It’s art,” John Goodman says. “It means different things to different people: You throw it up and put your own spin on it. It makes you think. But it can’t be explained. It’s got to be seen or experienced.”