Mike Birbiglia

Hometown: Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

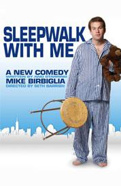

Currently: Making his off-Broadway debut in Sleepwalk With Me, an autobiographical one-man show about Birbiglia’s funny—and potentially lethal—history as a sleepwalker.

Drama Is Easy: In 1984, a few months shy of his sixth birthday, Birbiglia heard his calling. Or so he believed. “I was going to be a breakdancer,” he remembers. “Like in the movies Breakin’ and Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo. Did you see those?” He laughs. “I was convinced that this would be a great living.” As the years passed, he settled for the writer’s life, having becoming a prolific if not polished poet before the age of 10. Then came high school, and once cast as milkman Howie Newsom in Our Town, Birbiglia discovered his true life’s passion: not working too hard. “I took a drama class because I thought it’d be easy, which it was!” he says, unapologetically. Plays were easier on his eyes than, say, science books. “They were triple spaced, and I’d read them fast. It was, like, Macbeth is easy. Bring on Angels in America!”

Killing ’Em Softly: While majoring in playwriting at Georgetown University, Birbiglia formed a sketch comedy group and won a “Funniest Man on Campus” contest. That led to a regular slot at the famed nightclub D.C. Improv, where he developed his wry, soft-spoken standup technique. “I don’t like comedy that beats you over the head,” says Birbiglia, who can kill a crowd with a pregnant pause and the word “oh.” As he explains, “Sometimes comedians try to overcompensate with energy and volume when they really don’t have anything else. I mean, Chris Rock shouts. But his content is so good, it doesn’t matter.” Birbiglia’s also not big on swearing. “I see a lot of great comics get tuned out because they say [insert f-word here]. I’ll use it when it’s justified, and if it works. But you don’t want it to be a pacesetter. And there are a lot of other words you can use.”

So Now What? Birbiglia made the rounds on the comedy-club circuit, and in 2004, he released his first album, Dog Years. “I didn’t realize this, but comedy fans listen to your album, and if you do your old material at your shows, they’re like, ‘We know this. What do you have to say now?’ It’s not like music, where people want to hear the old stuff again and again.” Falling back on a one-man show he’d written in his spare time, Birbiglia began interweaving personal vignettes into his sets, like the one about a girl he had a crush on at Georgetown. Typical stroke: “I kept running into her on campus. [Pause.] Because I was following her.” It was another “eureka” moment. “The response was bigger in terms of laughs than my previous material. I felt like I was onto something.”

Meeting Mr. Lane: As he sharpened his confessional, Sedaris-like tone on subsequent albums and essays for radio shows such as This American Life, Birbiglia also taped some specials for Comedy Central and eventually landed a pilot for CBS. He cleared his tour schedule except for a gig at Caroline’s Comedy Club in New York—and Nathan Lane just so happened to be in the audience. The Tony winner was starring in November two blocks away at the time and was already a Birbiglia fan. “He had one of my albums and had seen my Comedy Central special. He wrote me this really nice note, and I kept it on the mirror in my dressing room while I was shooting the pilot in L.A.,. Just so I could see it and think, ‘Well, Nathan Lane thinks I’m funny. That’s something.’”

Bedtime Story: Frustrated by his lack of creative power during the pilot shoot, Birbiglia decided it was time to get back to his one-man show—a goal that kept getting pushed aside since television work had better perks, like paychecks. Working with director Seth Barrish, he embellished the autobiographical tales he’d been using in comedy clubs with more serious material: his long history of sleepwalking, caused by a condition known as Rapid Eye Movement Behavior Disorder. “We workshopped the show in comedy clubs and theaters, which was very helpful,” Birbiglia says. “You get a sense of what’s getting laughs and what people are listening to. Seth once told me, ‘People see standup comedians to hear what they’re going to say that’s funny. But people go to the theater to know what the playwright has to say, period.’”

Careful What You Wish For: With a helpful “Nathan Lane presents…” credit, Sleepwalk With Me opened off-Broadway in mid-October and has just been extended through March. Now Birbiglia is facing challenges that didn’t matter in standup, like sharing not-funny stories about jumping out of a window while still asleep. “Sometimes I’ll get laughter when telling it and I didn’t know how to handle that,” he says. “But Seth was like, ‘Just stay in it, until they understand what it was actually like to be in that situation.’” Then there’s other stuff, like cellphones going off despite the show’s hysterical rant about them and people texting during the show. Birbiglia is fine telling an audience how his disorder requires that he sleep in a zipped-up sleeping bag with mittens on, to prevent him from unzipping it and walking about. But he’s less comfortable with morning news shows asking if they can film him getting ready for bed. “It’s like going up to a punk band and smiling and saying, ‘Get all angry!’” he says. “That’s why theater is great. It’s a real moment with an audience full of real people.”

Related Shows

Articles Trending Now

- Good Night, and Good Luck, Starring George Clooney, Opens on Broadway with Glitz and Glam But No Egos

- Adrienne Warren and Nick Jonas Open The Last Five Years, Jonathan Groff Dances as Bobby Darin and More on The Broadway Show

- All Aboard for Pirates! The Penzance Musical: The Swashbuckling Saga of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Comic Operetta