Three Directors on the Spectacular, Provocative Legacy of Harold Prince

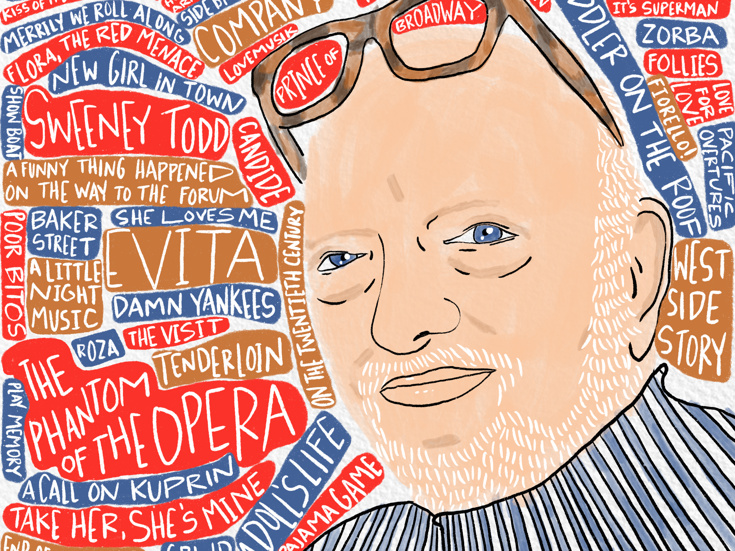

(Illustration by Ryan Casey for Broadway.com)

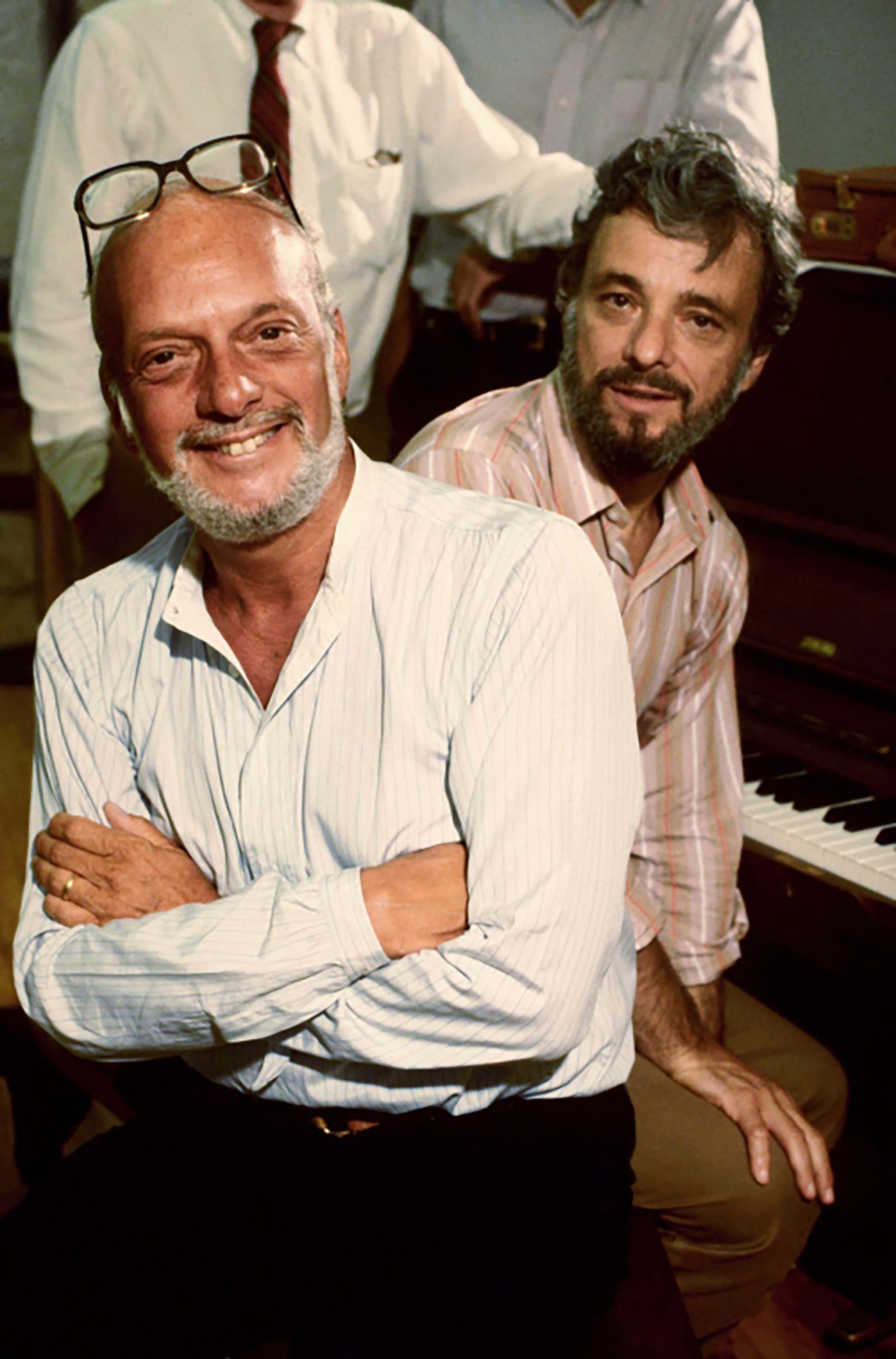

When I interviewed the director Harold Prince in his offices in Rockefeller Center in 2018—offices that were wallpapered with reminders of his decades-long career as a prolific theater producer and director—I broached the subject of mortality. Stephen Sondheim wasn’t worried about being remembered after his death, I reminded him.

Prince grinned. “He doesn’t have to worry about it. It’ll happen. I have to worry about it a little bit."

Just over four years after he passed away in 2019 (at the age of 91), Prince’s legacy is shining brightly in the Theater District. The new musical How to Dance in Ohio, a project that Prince nurtured in its earliest stages, is running at Broadway's Belasco Theatre and is dedicated to its champion's memory. Meanwhile, revivals of three musicals that Prince originated as a director—Cabaret, Sweeney Todd and Merrily We Roll Along—will soon be playing simultaneously on Broadway stages. (Cabaret will complete the trio when it begins performances in April.)

“There can never be another Hal Prince,” said Sweeney Todd's latest Broadway director Thomas Kail, “in the way that there can never be another Norman Lear, another [Steven] Spielberg, another Miles Davis.”

Kail has been in awe of Prince’s legacy as far back as he can remember. “I joked for many years that my Mount Rushmore has four faces on it, and they’re all Hal Prince,” he said. The two met and became close when Hamilton was playing the Public Theater in 2015. “He came to see the show. I asked if he would be interested in me coming over and sitting down at his feet while I listened to stories and he had a tuna sandwich, and he said yes to that.”

"There can never be another Hal Prince."

–Thomas Kail

Prince’s passion for the theater—not just making it, but seeing it—was always on display, Kail said. “He would talk about it with this incredible verve every single time, whether it was a thing that he had seen the Berliner Ensemble do in 1960-something, or something that he had seen one week prior. He loved the theater.”

Kail found endless inspiration, not just in the impressive scope and size of Prince’s work (“Hal could work on the largest canvas”) but, equally, in his ability to be inventive within strict limitations. “I saw Phantom [of the Opera] and I thought, oh my gosh—it’s a black box. This whole thing. His resourcefulness was not always remarked upon.” When faced with directing the revival of Sweeney Todd—the original, Prince-directed production premiered in 1979—Kail simply hoped to emulate Prince’s spirit of showmanship. “I wanted to deliver a show that was entertaining as heck and thrilling and scary—things that Hal was deeply interested in. Ultimately, the most important thing is I wanted to make something that I thought Hal would like.”

Most of all, Kail said, he’s inspired by the audacity of Prince’s work—the willingness, especially, to be uncommercial. Consider, for example, a musical about a homicidal barber. “If I came to you tomorrow and pitched you the plot of Sweeney Todd, you’d send me to the back of the line. But he was undaunted. He asked his questions in the theater, and he was always grappling with something substantial. There was a courageousness and fearlessness to the work that he chose to make.”

And Prince was truly making the shows he directed. For Cabaret, Prince came up with the crucial conceptual architecture of the show, dividing it between real-world scenes and metaphorical ones that represented Germany’s descent into fascism. It was “the first ‘concept musical,'" said director Rebecca Frecknall, whose production of Cabaret opens at the August Wilson Theatre this spring on the heels of its lauded 2021 run in London's West End.

"I’m not sure we’ll ever be able to determine the full extent of Hal’s influence on musical theater." –Rebecca Frecknall

In 1966—relatively early in his directorial career—Cabaret revealed Prince to be a director eager to challenge and confront audiences with politically charged work. On the first day of rehearsals, the 38-year-old director showed his cast a photograph from Life magazine—depicting white kids snapping and snarling at Black children—and asked the cast to identify the time and place of the picture. The point was that what looked like Munich, 1928, was in fact Chicago, 1966. In Prince’s vision, Cabaret wasn’t just about Weimar-era Berlin—it was about the turbulent political times of the United States in the 1960s. The show’s set design featured a trapezoidal mirror that reflected the audience, placing them in the action to seductive, discomfiting effect and anticipating the immersive quality of future productions of the show, including Frecknall’s.

“It must have been so provocative in its original production,” she said. “I was inspired by the boldness of the form. I wanted to honor the revolutionary feel of the work and its hugely important political conversation.”

(Photo: Marc Brenner)

Prince’s work on Cabaret alone—Frecknall calls it an “ignition”—leaves a huge legacy, she said. “The impact of the show on the form has been so vast, I genuinely don’t know if another piece has been as radical or continues to be as influential. I’m not sure we’ll ever be able to determine the full extent of Hal’s influence on musical theater."

And then there’s the show mostly remembered for the way it flopped. In 1981, the original production of Merrily We Roll Along—telling the story of three old friends, in reverse-chronology, from embitterment to idealism—closed after just 16 performances and 44 previews. Prince admitted he couldn’t make the show work. (The book was “too damn complicated,” he wrote in his memoir Sense of Occasion.)

"When you sat in a Hal Prince show, what you were guaranteed was story, story, character and story." –Maria Friedman

By the time Maria Friedman came to direct it, she was able to “look at it with a clear, fresh eye,” she said. Opening on Broadway in 2023 after an off-Broadway run at New York Theatre Workshop in 2022, Friedman’s production of Merrily We Roll Along turned out to be, to borrow a lyric from the show, a “genuine walkaway blockbuster” hit.

With the benefit of decades of hindsight, Friedman was able to diagnose one of the problems with Prince’s production. “You can’t cast young people,” she said. “The piece requires you to believe these characters have had a rich life full of possibilities. We need to trust they’ve taken some wrong turns along the way.” Under Friedman’s direction, Merrily We Roll Along became the story of just one of the three friends: Franklin Shepard (played by Jonathan Groff). It is a memory piece, inhabiting and following that character’s perspective.

That clarity of approach, Friedman noted, undoubtedly owes something to important lessons she’s absorbed from Prince’s work. “When you sat in a Hal Prince show, what you were guaranteed was story, story, character and story,” she said. “That was the foundation. Everything starts there. That was key to informing me as both a director and a performer.”

Even though the failure was heartbreaking, Prince’s recollection of developing Merrily was a happy one. “I cannot remember being happier waking up each day and going to rehearsal,” he wrote in his memoir. “And each evening I would return home filled with the pleasure of working with that cast. There was so much enthusiasm, so much creativity, and collectively it was a party.” There’s little doubt that Prince would have been touched by the enthusiasm and creativity that has been poured into the new Merrily—and heartened by its success. Apart from anything else, he would’ve loved to have enjoyed the show as an audience member.

“The house is full, and the audience is waiting for something marvelous,” Prince said to me, describing a thrill familiar to every theater lover. “The lights go down in the theater and they applaud like crazy before the show starts… Nothing beats it.”

There’s one last aspect of Prince’s legacy worth a mention: his characteristic way of perching his eyeglasses on that impressive forehead—all the better to see you with, presumably. Kail admits he has adopted the look. “For someone that used to have excellent vision who now can’t read anything without them, I was a little bit happy that I got to finally put them up on my head,” he said. "They went straight up there.”