Playwright Amy Herzog Gambles Her Soul in Mary Jane but Seizes the Pen in An Enemy of the People

(Art by Ryan Casey for Broadway.com)

For Amy Herzog, there are two distinct perks of adapting an existing property over writing an original play—a dichotomy that’s top of mind for her in a Broadway season featuring both her deeply personal play Mary Jane and her new adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s 1882 drama An Enemy of the People. Pragmatically, adapting solves the issue of writer’s block. “It's very comforting to be able to turn to the next page and have something there to begin from,” says Herzog, who envies the disciplined writer who can produce new ideas on command. “I don’t think if I sat down for two hours a day, I would have a play,” she says. The second benefit is emotional: “It feels safer to adapt than to write a new play,” Herzog freely admits. “I feel like my soul is a little bit less on the line.”

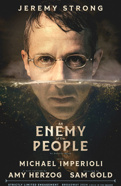

As if this Broadway season were designed specifically to test that appraisal, An Enemy of the People opens March 18 at Circle in the Square Theatre, just a few blocks north of the Friedman Theatre where, just two weeks later, Rachel McAdams starts performances in Mary Jane. In An Enemy of the People, Jeremy Strong and Michael Imperioli lead a nearly all-male cast (Victoria Pedretti being the only exception in the principal company) in a play that Herzog characterizes, in brief, as “men arguing about politics.” Few descriptions could be farther from Herzog’s typical work, and even she acknowledges, “I had to convince myself a little bit that I could do that.”

(Photo: Emilio Madrid)

Meanwhile, Mary Jane was arguably already Herzog’s most exposing play when it debuted off-Broadway at New York Theatre Workshop in 2017, depicting a mother (played then by Tony-nominated Leftovers and Gilded Age star Carrie Coon) whose life is consumed by the daily trials of caring for a child who has long outlived his life expectancy. At the time, she and her husband Sam Gold (who helms An Enemy of the People) were steeped in a community of parents and caregivers as they raised their eldest daughter, who was born in 2012 with a rare muscular disorder, nemaline myopathy. Their daughter died last July at the age of 11.

“There’s a lot of Henrik Ibsen to hide behind,” she says about An Enemy of the People. “Mary Jane—it’s me out there.”

(Photo: Joan Marcus)

Throughout the 2010s, Herzog dropped pieces of herself into her sharp, rich, character-forward plays, earning a Pulitzer Prize nomination in 2013 for 4000 Miles—a dramatic comedy that brought a version of her grandmother to the stage. But for her Broadway debut a decade later, she found herself tucked safely inside Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, fashioning a trimmed-down, piercing version of Nora Helmer’s story of liberation, directed by Jamie Lloyd and starring Jessica Chastain. It was her first adaptation project but one that didn’t scare her. “I just felt so inside that play that I didn't have too much imposter syndrome about it,” she says. It earned a 2023 Tony nomination for Best Revival of a Play.

“They were offering an adaptations class,” she mentions about her time as an MFA student at Yale. “I never took one.” She did, however, take a class in translation as a Yale undergraduate and held onto a few rules of thumb—one being the idea of preserving a play’s sense of foreignness: “There should be some kind of whiff of the fact that it's translated baked into the translation. I really like that idea that you don't want to disguise it as a new piece of American fiction.” Still, what prepared her most for A Doll’s House was her years reading and seeing different versions of classic plays, gradually refining her own ear. “I felt like I had an instinct about how to do it—about how to take those words and turn them into words that I could picture actors speaking.”

Herzog grants that her time with A Doll’s House gave her valuable practice as an adapter, but says it did little in the way of unlocking Ibsen himself.

(Photo: Emilio Madrid)

“I feel like I couldn't be farther from him,” she says, speaking more about Ibsen the man than Ibsen the playwright. She paraphrases one of his notorious quotes about his distaste for children, music and flowers—digging, in her writerly way, for the correct order of the list so it would land with its intended grouchy punch. “He was just cantankerous and extremely ambitious. He wrote these extraordinary character plays, which are among my favorites, but I think my approach to writing couldn't be further away."

You’d also be hard-pressed to find any shared algorithm between A Doll’s House and An Enemy of the People. While she drew out A Doll’s House’s sense of intimacy and introspection in her hit revival just last year, the “rangy,” “polemical” and “sometimes melodramatic” An Enemy of the People poses an entirely different challenge. “In a way, I feel more distant from him because I'm confused about how he did that—about how he found his way to writing both of those plays.”

"There are two roles for women in this play and I’m cutting one of them. That felt violent." –Amy Herzog

“He wrote some of the greatest women characters we have in the whole canon,” she continues, pointing, of course, to her beloved Nora as well as the equally abundant Hedda Gabler. “And he was also capable of being kind of—” she pauses searching for the right word. “A little dull.” Not in the boring sense she clarifies, but “not necessarily perceiving gender dynamics in their total subtlety.”

It’s an observation that brought Herzog to the thorny choice to cut the character Katherine, a decision that she found necessary but painful nonetheless: “There are two roles for women in this play and I’m cutting one of them,” she intones, narrating her inner monologue. “That felt violent.” Katherine is wife to Ibsen’s protagonist Dr. Thomas Stockmann (Strong)—the play’s champion of truth who tries to expose the water contamination in his town’s public baths.

"I just couldn't get behind those scenes,” she says. “She was sort of there to argue to her heroic husband that he should consider the family. I was just like, ‘Where is Nora? Where is Hedda?’” Herzog ended up finding glimmers of these women in Dr. Stockmann’s daughter Petra (played by Pedretti): “That's where I put my energy and let Katherine's loss be something that Thomas was dealing with and motivated by psychologically.”

It may not be Herzog’s soul on the line, but there are stakes behind choices like these, each one shaping the new lens through which audiences will be experiencing Ibsen’s nearly 150-year-old play. And at the end of the day, how gently or violently her new piece is molded from its source material is riding on the murky negotiations between a 21st-century American artist and a long-dead Norwegian playwright whose creative vision—and even his lexicon—have gone with him to the grave.

“I don’t even fully understand what Dano-Norwegian is,” says Herzog, confirming that she neither reads nor speaks the language of 18th and 19th-century Norwegian urban elites in which Ibsen wrote his plays (she worked from a literal translation by British writer Charlotte Barslund). “Even in Norway when they want to do An Enemy of the People, they're translating it into contemporary Norwegian. I found that very freeing to know.”

"There’s a lot of Henrik Ibsen to hide behind. 'Mary Jane'—it’s me out there."

–Amy Herzog

It certainly gives Herzog additional creative slack, facilitating her ability to massage the language into something “contemporary without feeling anachronistic”; "speakable,” and “not just for actors who went to drama school.” But even if Herzog had the option of resurrecting Ibsen for a brain-picking session, serving his original intentions is not necessarily how she defines her role as an adapter. “I don't know that I owe him anything other than a really good-faith attempt to understand what he did before changing anything,” she says. “And that really has more to do with the play than the writer,” she specifies. “I feel like I owe the play something. I owe the play full comprehension and attention to lifting what is most still alive right now.”

And so much of it is still alive—from the dystopian power of groupthink to questions about the responsibility of the individual within a society trapped in its own inertia. Name a current topic in American liberal discourse and you’re likely to find it hovering over Circle in the Square Theatre. But as much as Herzog fancies herself hidden behind Ibsen’s 150-year-old ideas and cantankerous face, her craft, her mind—and yes, even her soul—are in plain sight.

Related Shows

An Enemy of the People

Show Closed